Muslims in America

April 9, 2012

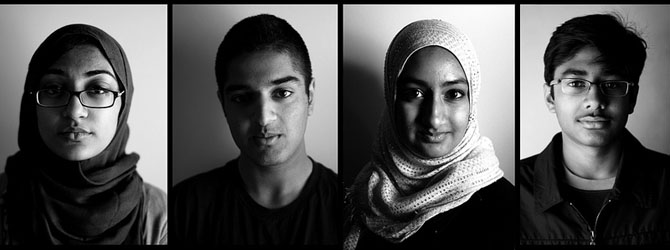

In our April issue, Special Report documented the intersection of cultures for students, parents and teachers. One such story focused on freshman Anwar Ali-Ahmad, his parents and their experiences as a Muslim family in America. Here, we feature four more stories of students with Islamic backgrounds.

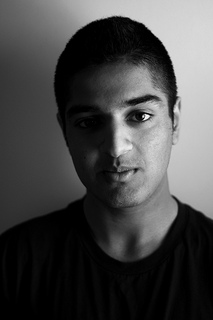

Preaching and praying

Every Friday, a handful of students trickles into room B212 for the weekly meeting of the Muslim Student Association. After socializing and perhaps eating some lunch, the club-goers settle down. Their attention falls upon sophomore Zuhayeer Musa as he delivers a Khutbah, an Islamic sermon, and leads a prayer; the two combined last 10 to 15 minutes, and the club disperses a few minutes before the bell signals the end of lunch.

Musa joined MSA back in his freshman year, after his mother told him about the club. He has since risen to the position of Khateeb, or sermon-giver. The sermons typically expound upon the core tenets of Islam; Musa stated that common topics include “doing righteous deeds, caring for others, helping the poor [and] going to pilgrimage,” although he does try to add a youth-related spin to them. Some khutbahs, like “take five before five” — a khutbah that stands out in Musa’s memory — are already directed towards youth. This particular one talks about taking advantage of youth before old age, health before sickness, richness before poverty, free time before business and life before death.

Born and raised a Muslim, Musa has always followed the religious values embodied in such sermons, and believes in practicing and adhering to Islamic values in the manner that the religion dictates. Musa noted that he did encounter a few minor religious hitches before the age of seven: He ate non-Halaal meats and participated in dramatic plays that clashed with more conservative Islamic values. While he does grant the individual’s right to a degree of flexibility in practicing Islam, Musa believes that the religion ought to be followed as written.

“I have been in a few plays before where I had to dance with a girl, but … I was young then, so I wasn’t really educated on this religion,” Musa said. “I think [the youth] should be able to do these things since we’re in an environment in America … But I think it’s better to … just go with what the religion suggests you should do instead of following the society.”

Musa does believe, however, that Muslims can follow their religion and still live out their desired lifestyles.

“Some people find religion [to be], ‘You have to follow this, this and that,’ but you should be able to … actually enjoy life as well as follow your religion,” Musa said. “There’s always a path that does fit you and abides by the religion.”

Musa has not had many personal conflicts with his religion, although he does have qualms about the way Islam is treated in the media. According to Musa, coverage on terrorists should not be focused solely on Muslims.

“I’ve never felt uncomfortable, because I know this is America, this is my country. So I have to support it in any way I can, and it should in turn support me as well,” he said. “[But] yeah, I’ve felt for my people … it’s not right to just point fingers at someone … just because they’re a Muslim.”

Musa believes that educating people about Islam is the key to eliminating fear of the religion. As for those who already practice Islam, Musa believes that education will help them distinguish between what is religiously right and wrong and serve as basis for their morals, as it does for him.

“[Being religious] makes me feel like I’m on the right track, it makes me feel I can depend on my God, just like there’s somebody out there,” Musa said. “It makes me feel accomplished in the sense that I actually have something to follow.”

Setting the example

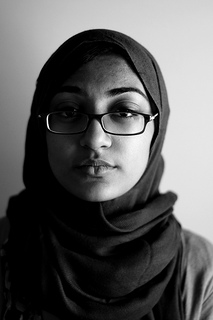

Her mother decided to do it first. Then her older sister followed suit. It made sense for her to do it, too. So the summer before freshman year, junior Dania Khurshid decided to don a hijab — a traditional headscarf worn by Muslim women — as a display of her Islamic identity.

“For me, it was not a ‘Why?’ decision, it was a ‘Why not?’” Khurshid said. “The friends I had were very accepting and I was starting high school anyway, and I knew people did [wear hijabs]. And this is a pretty accepting community. It’s not like … I was going to run into bigots and racism.”

Khurshid attended Islamic Sunday school from kindergarten to tenth grade, and continues to visit as a teaching assistant. According to her, she learned that those who wear hijabs should be “the best of Muslims and … an example for others.” This can be difficult; she observes that religious convictions have taken the backseat in modern conversation and society.

“At times, it gets really hard. Like especially these days … [it’s like],‘Why am I doing this? Is it because I grew up with it or because I believe in it?’” Khurshid said. “I always come back to those moments when life really sucks and I ask for help and I get it. And so that’s kind of kept me believing.”

Aspects of her religion and everyday life have clashed; for example, like many other Muslim students, she must rearrange her five daily prayers around the school schedule. She also initially struggled with another major religious expectation — fasting — when she adopted the practice in fourth grade.

“When I was little it was hard, because obviously when you’re eight years old you really want to eat some lunch, but it’s a … discipline thing,” Khurshid said. “If I broke my fast, I would feel incredibly bad, I would feel incredibly guilty, and I would feel like I was failing — not just God, but myself … It gets a lot easier … it’s not a problem for me anymore.”

Khurshid views her internal religious conflicts as marginal, but she has encountered instances of her religion being called into question by others — starting at the age of six, on Sept. 11, 2001.

“My friend told me, ‘Yeah, it was Muslims that did it’ … I think the words that came out of my mouth were, ‘That’s not a Muslim,’” Khurshid said. “I had just started learning about Islam and how great it was … I’m like, ‘You’re crazy, that can’t be.’”

Especially in the aftermath of 9/11, antagonism toward Muslims has been openly flaunted in public forums. In Khurshid’s experience, articles with Muslim names in the headlines usually herald bad news and hateful comments. She decided to stop reading them altogether.

“I’ve experienced people who think people who are religious aren’t as intelligent because we don’t comprehend the fact that there’s no Spaghetti Monster in the sky,” Khurshid said. “It’s a little weird to be like, ‘Yeah, I’m religious. Is that so bad?’”

A shift to agnosticism

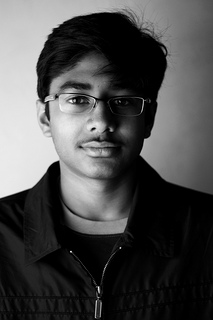

Raised in a Muslim household, senior Arif Hasan abides by Islamic values — kindness unto others and abstaining from drinking, among others. But he isn’t a Muslim. He’s agnostic.

Hasan did practice Islam at a younger age, and became religiously aware in middle school, when he began to explore his curiosity concerning Islam. He found answers through his grandmother, who elaborated upon the tenets of Islam and the rationale behind some of its practices.

“Having these spiritual, religious talks made me really intrigued, and it made me want to be more in touch with the Islamic religion,” Hasan said. “I didn’t observe every aspect of the religion, but I definitely became more spiritually in touch with the main aspects and main concepts that the religion preaches.”

While in middle school, Hasan made it a point to pray on a daily basis, even if he didn’t pray five times a day as prescribed by the religion. According to Hasan, he drew satisfaction from believing that his actions were in line with a larger, guiding principle. And yet, Hasan’s connection to the religion diminished as he began to question his surroundings, including Islam. By the time he commenced his freshman year, Hasan found himself less religiously active, praying only on days of particular religious importance. His disconnect from Islam grew until he no longer recognized the value he once found from adhering to the religion, culminating in his adoption of agnosticism.

Although agnostic, and although he may no longer agree with some of the religion’s practices — he attends dances and calls himself “liberal on just about everything” — Hasan still attributes his moral framework to Islam.

“I think my current set of morals probably has been colored by my earlier religious [experience],” Hasan said. “If I hadn’t been religiously connected at any point, I wouldn’t have really given thought to morals at all, and I would’ve just lived life how I wanted.”

Hasan’s self-removal from Islam has carried into his interaction with non-Muslims, including experiences involving negative portrayals in the media or in everyday conversation. Hasan is bothered by misinformed attitudes towards Islam, acknowledging that much of the ignorance surrounding the religion may stem from what he perceives as people’s treatment of Muslims as scapegoats post-9/11. He has, however, come to accept as the negative comments that result from this ignorance a trend that will “blow over in time.”

“I’ve started to identify myself less, and less, and less with the religion, so I take things less personally,” Hasan said. “But, also, I just realized that you really can’t do anything about how people feel sometimes, and, you know, they’re not hurting me in any way, so I don’t feel too strongly.”

Hijab as empowerment

People ask if her father forced her to wear it, or if she even wears it in the shower.

To most questions like these, junior Ismat Junaid answers no.

She began wearing a hijab the summer before her freshman year, of her own accord, and she does indeed take off the headscarf while at home — especially when taking showers.

Though she acknowledges there are many accounts of women being pressured into wearing hijabs, Junaid asserts that such force is entirely immoral. According to her, choosing to wear a hijab simply translates to a constant reminder and public symbol of faith.

“I wouldn’t say not wearing a scarf makes you a bad Muslim. Your deeds and what you do and what’s your inner self, that’s what makes you Muslim,” Junaid said. “It does help you. It helps you becoming that better person so that’s really all it is.”

On top of that and the commonly-cited reason for wearing a hijab — modesty — Junaid says there are additional benefits.

“In modern society, we’re so fixated on appearance and beauty and stuff … Being able to cover your hair just allows people to look past that barrier, into your personality,” Junaid said. “Most people think, ‘Oh hijab, it’s oppressive,’ where really, it’s not. It actually empowers women … People are a lot more respectful to you, they understand your morals, your values.”

Within this community, she has not fielded derogatory comments about her hijab or her faith. When she was younger, around the time of 9/11, she remembers neighbors remaining friendly and helpful; but she also remembers high levels of tension.

“My mom … wasn’t able to leave the house and the neighbors would bring the groceries and do all the things,” Junaid said. “She went to Costco once and this dude, this guy actually came up to her and was like, ‘Aren’t you scared for your life?’ She got really scared after that.”

Junaid does find it frustrating that many people tend to extend negative portrayals of Muslims from the media to the entire group of people.

“They don’t really understand that those [extremists] aren’t the face of Islam. These extremists aren’t even Muslim in my opinion,” Junaid said. “I feel like all of it comes down to 9/11. And it’s just those negative feelings that are associated with it. I mean, it was an extremely horrible event and of course people are going to be angry, even I’m angry about that. But they have to understand that those extremists, they’re not what actual American Muslim people are like.”