Every year, there’s Homecoming. Every year, varsity plays to the exhilaration and excitement of the Friday crowd that bears the chilly fall night just to see them win. Every year, the expectations are set for each class in the Homecoming race. And every year there’s Homecoming Court.

The tradition

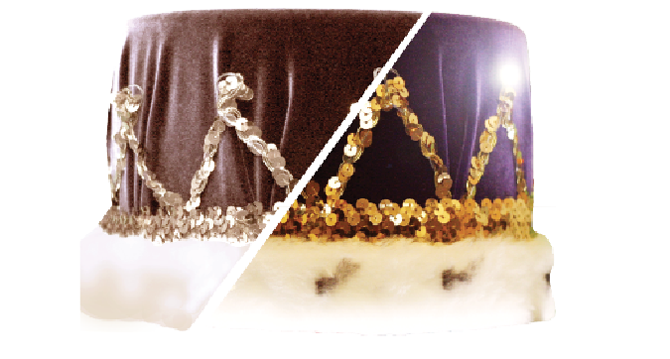

Typically, the Homecoming Court includes a King and Queen, usually seniors, nominated by classmates and then voted on by the entire student population. The winners are then crowned at the Homecoming rally or football game. MVHS crowned its first Homecoming Queen, Pam Meyer, in 1972.

“[The king and queen] are individuals who contributed to MVHS in some way, in drama, sports, art, leadership, and embody a positive attitude that everyone should follow,” ASB Treasurer senior and Homecoming Court member Kevin Chang said. “It’s an opportunity for individuals to celebrate school spirit.”

The controversy

In October 2010, the University of Arizona published an article praising the tradition of Homecoming Court where five boys and five girls are nominated who best represent the school through community service, leadership, school involvement, and commitment.

However, recently some have questioned whether this is actually true. The New York Times published an article in 2004 about gay students protesting Homecoming Court because many gay and lesbian students have been virtually absent since the tradition began. Their reports are inconclusive on the exact number of schools that now include gay and lesbian candidates, however they have noticed a few schools making the change.

“As a senior, I personally felt kind of awkward being on Homecoming Court because I didn’t know what it was for. I thought, ‘Why isn’t every girl up here?’ I didn’t get how we were selected,” said choir teacher Shari D’Epiro, who graduated with the MVHS class of 1979 and was voted Homecoming Queen the previous year

In 1992, the Los Angeles Times also covered the controversy at a small private Christian school in LA that cancelled the tradition altogether deeming it “un-Christian” and overly focused on beauty and popularity. In the 1972 yearbook, a student was quoted saying Homecoming is also a beauty pageant, referring to the Homecoming tradition.

Though most students would not call the current system of selection a “beauty contest,” many like junior Jasmine Tsai still see a relationship between the selected candidates and the one word she used to describe what Homecoming Court is based on: “popularity.”

Another question that arises in the discussion of Homecoming Court is whether or not students know the original purpose. Why continue a tradition that no longer has sentimental value for the students?

“If no one knows about Homecoming Court, then the school shouldn’t run it,” freshman Nish Ullagaddi said.

Yet, eliminating tradition is contested by most students. In a random selection of 30 students, just over half admitted that they did not know what Homecoming Court was for, but all of the students interviewed except one did not think it needed to be canceled.

“I don’t really know [what it’s for], but it’s a tradition, so we should continue it,” senior Shrestha Wadhwa said.

The shift

Homecoming Court itself has persevered through the years, and its evolution is significant. Originally, six girls were nominated to Court every year, who would then have the choice of choosing their escorts. It wasn’t until the mid-1990s that students could nominate boys to Court as well, but they remained as simply escorts. In 2005, MVHS crowned the first Homecoming King, Onur Erbilgin.

A noticeable trend is the high number of Leadership students voted onto Homecoming Court. This year, nine out of the twelve members are in Leadership. Although there were two nominees involved in football, one who was voted into Homecoming Court, the lack of diversity has caused students to become concerned with representation.

“[There is] a lot of talk about representation, like too many Leadership, not enough Lawson students, Kennedy being more represented, but it’s a voting process,” Chang said.

In the last four years, three Homecoming Kings were ASB officers; the fourth was a class officer. The exact same numbers were repeated for the Homecoming Queens in the last four years. When asked who they believed would be in court, sophomore Eric Huey simply said ASB President. In an effort to contend such ideals, senior Homecoming Court member and ASB vice president Christina Aguila considered dropping out of the race because she did agree with the point in participating.

“It should be based on personality, and it is a part of it. [But it’s] mostly based on first impression or the image of the person,” sophomore Chris Chang said.

Around a decade ago, the Court had a more diverse group of students. In 1986, the Court included the head varsity cheerleader, ASB president, a varsity cheerleader, a dance team member, ASB secretary and a Madrigal (a form of music from the Renaissance) member.

“There was no leadership class, so the majority included football players, senior class officers, cheer and dance team captains, yearbook editors, journalism editors, anything that put you out in the public eye with the school,”Attendance Technician and MVHS Class of 1999 alumnus Calvin Wong said.

He attributes the shift to the creation of a Leadership class, greatly increasing the number of seniors involved in school and the issue with football players in Court having to be with their team before the game rather than out on the field with other Court members.The football team not being able to participate was a trend that math teacher and Class of 2000 alumnus Brian Dong also noted.

“I really don’t know, to be honest, [what Homecoming Court is for]. I think it’s just a tradition all schools have. I’m a big fan of traditions, but we could look at how we vote and who can participate” Wong said.