The music industry’s attack on peer-to-peer software will not deter pirates

The music industry’s attack on peer-to-peer software will not deter pirates

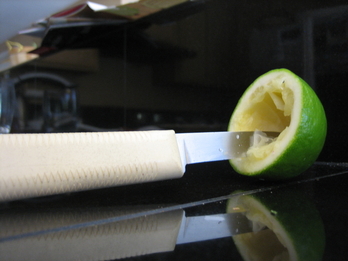

The lime has been squeezed, pulped, and tossed. LimeWire cannot be juiced any longer.

On Oct. 26, federal judge Kimba Wood of New York’s southern district court issued a permanent injunction on LimeWire that directs the company to stop supporting its software, primarily on the grounds that the company encouraged copyright infringement. While LimeWire did harass the music industry, eradicating the company’s software outright will not achieve the Recording Industry Association of America’s goal of curbing piracy. Technology is constantly changing and evolving to meet the needs of the people. If the music industry wants to survive, it needs to do the same.

There is no doubt that LimeWire deserves the injunction imposed upon it. According to Wood, LimeWire acknowledged that its users used its software for copyright infringement—hence their internal document “Knowledge of Infringement.” Nonetheless, she stated that the company made no serious effort to discourage the illegal sharing of copyrighted material. LimeWire’s negligent attitude towards infringement, not to mention the host of viruses it propagated, severely damaged the viability of the peer-to-peer software, in which users connect with each other to share files without the control of a central host.

However, shutting down LimeWire will not entail a noticeable dip in piracy. As history has shown, when one P2P is shot down, another one emerges in its wake. First there was Napster, then Kazaa, then Limewire. Now, pirates will just flock to other file sharing services, including FrostWire, BitTorrent, and more.

The RIAA has two options to resolve the piracy quandary: eliminate P2P technology in its entirety or reform the music industry. Outlawing all fire-sharing technologies is not feasible, especially since organizations like Pirate Bay with headquarters outside of the US are not under American jurisdiction. Nor is eliminating P2P technology just—P2P is simply a tool to share files. Consumers, not P2P technology, are choosing to illegally share music.

In order to minimize piracy, the RIAA should stop its never-ending chase of P2P technology and should instead work to modernize the music industry to meet the needs of the average consumer. The large number of virtual pirates indicates that the people are not willing to pay $12 for a virtual album. Such a price may have been justified in the past, when music was solely distributed through CDs; however, the advent of digital distribution eliminates the manufacturing cost and the price of music should be decreased accordingly.

It is true that some people would prefer downloading free music over purchasing legitimate music. While decreasing the cost of music would not completely eradicate piracy, it would encourage financially-strapped consumers to pay for their media library.

The RIAA needs to devise a modern solution to the piracy problem, as their current methods strike consumers as cruel and abusive. The association’s erring judgement is best exemplified in the RIAA’s recent lawsuit, in which Jammie Thomas-Rasset was fined $1.5 million for pirating 24 songs. Such scare-tactics are not only excessive but ineffective—a pirate will not convert into a consumer if he is sued for every cent he possesses. If the RIAA wants to survive, it needs to stop viewing pirates as criminals and start perceiving them as potential customers.