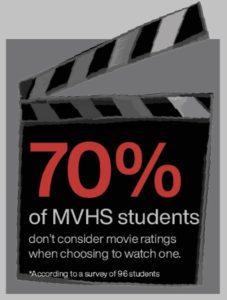

When “The Super Mario Bros. Movie” came to theaters in 2023, it was immediately slammed with poor reviews from critics for being too childish, shallow and lacking strong characters. In 2025, the story repeated itself when “A Minecraft Movie” released to poor reviews for similar reasons. However, both films shattered box office numbers — “The Super Mario Bros. Movie” made $1.36 billion at the domestic box office, cementing its position as the highest-grossing video game inspired movie. Similarly, “A Minecraft Movie” defied box office expectations by netting $157 million in its opening week, making it April’s most profitable box office debut so far. On sites that consider audience reviews alongside critic reviews, such as Metacritic, “The Super Mario Bros. Movie” did very well among audiences, scoring 8.2/10 compared to 46/100 from critics.

As reporter Erik Kain wrote in a Forbes article about “The Super Mario Bros. Movie,” “In any case, a lot of these movie critics must not play much Mario or know much about Mario because the magic is apparently lost on far too many of them. That’s a shame. This movie is absolutely great, a very faithful, very fun adaptation of one of the most popular and beloved video game franchises of all time.” This stark contrast between how audiences and critics perceive media isn’t new. Among critics, a trend emerged, especially in the past few years, where movies that prioritize being more lighthearted and fun are deemed as lesser works. The way we critique art, especially film and TV, has become narrow, with increased focus on things like depth, symbolism and overall complexity, as seen in the Forbes article. While these factors can be markers of quality, they aren’t the only thing that defines it. Sometimes, media’s sole purpose can be just to entertain, and that should be enough to satisfy critics and audiences alike.

While many critics aim to look for hidden messages and themes in media, perhaps the true meaning is that there is no hidden meaning at all. For many, there is a large appeal of things like “dumb” Hallmark movies or lighthearted comedies, purely because of their simpler nature and lack of deeper meaning or social commentary. These films, while starkly different from what many consider an archetypal “quality” film, offer a relaxing experience that promises a feel-good ending and doesn’t require the viewer to constantly focus on its intended message in order to enjoy it.

This problem extends to all different types of media, irrespective of their target age or audience. Films like “The Super Mario Bros. Movie” or “A Minecraft Movie” should not be attacked for not carrying a complex meaning or deeper themes because, simply put, the average child is not looking for these in a film. Rather, they are looking for pure entertainment value. Especially when it comes to events like awards circuits or checking off criteria such as a meticulously crafted script or deeply rooted symbolism, critics often forget work that prioritizes simplicity and pure enjoyment. The University of Vermont, when discussing film criticism, states that “Film criticism usually offers interpretation of its meaning, analysis of its structure and style, judgement of its worth by comparison with other films.” This implies that a film needs to meet these criteria, such as having deeper meanings, as well as strong structure in its script and dialogue. As directly written in a review from sportskeeda.com, “A Minecraft Movie struggles with critics but finds success in fans.” The review states how, while critics struggled to find meaning or purpose in the film, fans embraced the lighthearted nature of the film and the nostalgia it brought back to the game. The disconnect between what critics and audience members are looking for reminds us that the target audience should be considered in any artistic critique. If children’s novels, often purposely simplified to appeal to younger audiences, aren’t expected to hold the same weight as complex texts, then why should films have to do the same?

This debate even extends to schools. Many high school students feel the need to force themselves to find meaning in literature — a demand superimposed by the class curriculum that insists on deep analysis of every text, regardless of whether the text offers that analysis or not. While core texts offer opportunities for discourse, numerous supplementary texts or films are often jammed into the curriculum, often confusing students rather than allowing them to find insight in the text. For example, Honors American Literature students at Monta Vista are expected to analyze the children’s book “Make Way for Ducklings,” even though the author of the book, Robert McClosky, has said that his inspiration for the book was “noticing the ducks when walking through the Boston Public Garden every morning on his way to art school.”

If students are expected to analyze a book where even the author has stated there were no hidden meanings, then what is stopping students from pretty much dissecting and overanalyzing anything? This subconscious expectation that students are expected to find meaning in everything to overanalyze often takes away from the overall enjoyment of taking in content. Because students are expected so early on to analyze everything with a variety of lenses, they often lose the idea of taking in content for pure enjoyment. This overall culture leads to the over-critiquing of media even when the media itself is made just to give the audience a good time.

Ultimately, not every film or piece of art is required to be multi-layered and have deep levels of symbolism and real-world commentary. Sometimes, the intention is simply to entertain. A “good movie” isn’t defined by a single set of criteria — it can range from a thought-provoking drama to a lighthearted comedy. By recognizing this and broadening our understanding of what makes a film “good,” we allow art to flourish in its many forms — each one perfectly suited for its audience.