The Category 3 storm Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans on Aug. 29, 2005 and would later be ranked as the costliest natural disaster in United States history. The storm displaced an estimated 1.5 million people, and many were left to scavenge for resources within the flooded city. Despite fighting for survival, black individuals were labelled “thieves,” “immoral,” “needy” and “looters” by media depictions while their white counterparts were simply “finding food.”

This disparity isn’t surprising when considering who writes the news: journalism is increasingly dominated by predominantly white, educated, socioeconomically advantaged people whose coverage reflects their privileged perspectives on the world and inherently shares the biases they often hold. Journalism is often an exclusive club for individuals from similar elite educational backgrounds, making breaking into journalism an uphill battle for those without privileged financial conditions. Elite educational institutions have a firm grip on the industry — within major news organizations like the Wall Street Journal, 49.8% of editors and writers attended an elite college, defined as a school with a median SAT score of 1400 or above. Both SAT scores and admissions into elite colleges correlate heavily with wealth; among students with the same test scores, children from wealthier families are 2.2 times more likely to be admitted. A mixture of legacy admissions, better resources from expensive private schools and a higher likelihood of becoming a recruited athlete means the wealthy have a leg up in admissions.

In addition to staff members, 65% of interns at major newspapers have attended selective schools. This barrier prevents entry for those unable to afford a tuition of over $80,000 per year. Even if less affluent students can attend prestigious schools, the burden of student loans coupled with the industry’s low salaries means journalism often seems like an infeasible career.

For those who do enter the field, financial struggles persist. Journalism is not a high-paying industry, with a median pay of $57,500 per year, and many young reporters from less privileged backgrounds face insurmountable student debt. As of 2024, the median student loan debt is $53,213 for a master’s degree in journalism. The expectation that aspiring journalists should take on unpaid or low-paid internships further narrows the field to those who can afford to work for little or no pay.

Journalism’s elitist slant is exacerbated by corporate control of major news outlets. Six corporations — Comcast, Disney, Warner Bros. Discovery, Paramount Global, Fox Corporation, and Sony — own 90 percent of mainstream news, an overwhelming majority. Meanwhile, billionaires like Jeff Bezos of The Washington Post, Rupert Murdoch of Fox News and The Wall Street Journal, and John Henry of The Boston Globe hold these media outlets at their mercy, and on occasion, use their influence to protect their financial interests rather than serve the public good.

Corporate ownership directly impacts news coverage. Bezos reportedly pressured The Washington Post’s editorial board to uphold a free-market stance. As Bezos said, “viewpoints opposing those pillars will be left to be published by others.” This resulted in the resignation of opinion editor David Shipley. This type of editorial influence ensures that economic policies and corporate accountability are framed in ways that align with elite interests rather than challenging systemic issues or even just maintaining objectivity.

In addition to editorial control at the national level, the trend of media consolidation has proved detrimental to the survival of local news, furthering the media’s disconnect from the public. Between 2008 and 2020, the U.S. lost over 2,000 local newspapers, leaving many communities without reliable sources of information. Large conglomerates buy struggling outlets only to strip them of resources, prioritize profitability over investigative journalism and downsize local reporting staff. This loss has been so severe that some have referred to it as an “extinction-level” event for local journalism, particularly in rural and economically struggling communities where news deserts are most prevalent.

As journalism becomes more concentrated in an elitist perspective, its coverage suffers from a homogeneity problem, skewing toward the interests and concerns of the privileged. Issues such as labor rights, healthcare and wealth inequality are often covered through a singular, privileged lens, speaking to the perspective of policymakers and business executives rather than the people directly affected. The result? A media landscape dominated by individuals from affluent backgrounds who are less likely to grasp the struggles of the working class. As Heather Bryant, a journalist and founder of Project Facet, a collaboration infrastructure that connects news and information partners, describes, “most news coverage isn’t created with people experiencing poverty in mind.” Mainstream media tends to downplay economic hardships and is more likely to be less empathetic towards marginalized groups.

The news is often made for and by the rich; around half of those who make over $150,000 a year pay to read the news. These affluent, urban audiences who have the time and money to read their content are not as interested in local news. As a result, news outlets do not report the issues that directly impact smaller communities such as school board decisions, housing crises and environmental concerns.

Beyond the journalists themselves, the decline in physical newspapers by 75% from the 2000s has marked the turn to digital journalism and a new monetization system: subscriptions regulated by paywalls. Paywalls have made quality journalism inaccessible to lower-income audiences. As major newspapers charge anywhere from $2 to $47 per month for access, many individuals are effectively excluded from staying informed. Digital subscription models, while financially beneficial for publications, have also placed critical news behind a price barrier. Research shows that paywalls disproportionately limit access for younger, lower-income and nonwhite audiences, as families with minority backgrounds are more likely to live under the federal poverty limit than their white counterparts.

Local and student journalism mitigates this accessibility crisis. Unlike corporate-run publications and legacy media that sequester news behind costly subscriptions, student-run outlets are typically free or low-cost. With many student publications sustained through donations and community business ads rather than subscription revenue, they prompt civic engagement by making knowledge freely accessible to everyone, not just those who can afford it. This helps close the information gap, particularly extenuating the lack of access for younger audiences.

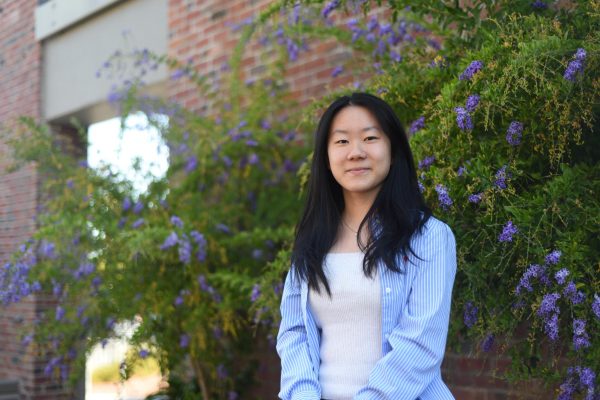

However, even student journalism is not immune to privilege. Many high school and college newspapers exist in relatively wealthy areas with students who have access to high-quality education and resources. While student journalists may not entirely escape the elitism of mainstream media, this reality presents an opportunity: we can use our platform to actively seek out and amplify underrepresented voices and report on issues beyond our immediate bubble. This challenges the myopic perspectives dominating legacy media, offering a structural corrective to their elitism. Unlike corporate outlets, we do not have the limitations of profit-driven goals dictating our coverage.

Ultimately, journalism should serve the public interest rather than act as a mouthpiece for those in power. By investing in local and student journalism — whether through readership or financial support — we can bridge the gap between the media and the people it is meant to serve.