MVHS sits on the ancestral land of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe. This land was and continues to be of great importance to the Ohlone people, who are the successors of the sovereign Verona Band of Alameda County.

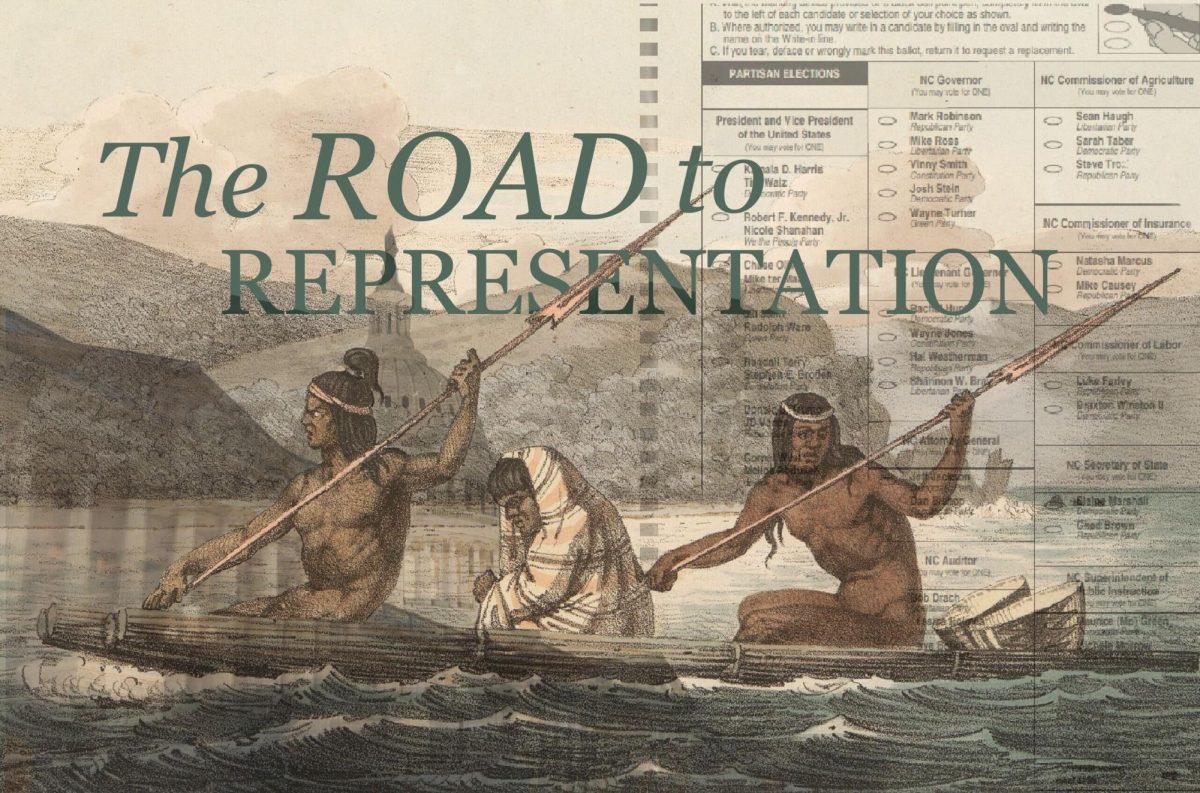

In the 2024 election cycle, over 170 Native American, Native Hawaiian and Native Alaskan candidates ran for office in the U.S., setting records and giving voters in 25 states the opportunity to elect or reelect an Indigenous leader. Among these candidates is Charlene Nijmeh, Chairwoman of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribal Council, who recently ran to represent California’s 18th Congressional District. While her campaign was unsuccessful, it was centered around remedying the lack of representation for her community.

“It’s very important that we have a seat at the table, because as representatives in the federal government, we would be able to protect our rights and govern ourselves on our land,” Nijmeh said. “So it’s very important that we have more Indigenous people at the table and in Congress making these decisions for Indian Country.”

Despite Native Americans making up over two percent of the U.S. population, Native Representatives hold only two seats out of the 435 seats in the House of Representatives and only one Native Senator. According to Advance Native Political Leadership, an organization dedicated to supporting Native communities, Indigenous leaders make up just 0.07% of elected officials. The organization’s website states that in order to reach representational parity in elected office, more than 17,000 Indigenous leaders must be elected at all levels of government.

However, Homestead High School English teacher and active Indigenous community member Shawnee Rivera believes that cost is a major barrier for would-be candidates when deciding whether to run. Although she is passionate about the representation of Native people, the price tag associated with a campaign deters her from running for office.

“Do I want to raise money and fundraise for millions of dollars to run for something when those millions of dollars can be used to take care of my elders? No, I’m not doing that,” Rivera said. “It literally excludes everybody who’s not middle or upper class, so a majority of the population can’t consider being a voice for others unless they have financial backers. That’s a disgusting system.”

Still, Rivera believes that Indigenous representation in government would be a step forward in recognizing millions of Native people. These values are reflected in Nijmeh’s work as chairwoman, which is centered around gaining the federal recognition of Muwekma Ohlone sovereignty and reinforcing “partnerships and allyships with Congresspeople.” Federally recognized tribes may apply for funding from the U.S. government to finance anything from housing to monthly packages of healthy food for eligible applicants. It is important to the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe, which has been present in the Bay Area long before the U.S. government was even formed, to receive federal recognition.

“Our tribe, and most of the tribes along the coast, are fighting to get our status clarified, but the government is resisting to acknowledge us, and we’re unprotected,” Nijmeh said. “We’re always working on that. We just got a new president, so the work continues, but we’re always focused on staying visible and active and visiting Congress often to make sure that they still see us and they still hear our voice.”

Beyond federal recognition, Rivera also believes that Indigenous leadership would advocate for environmental justice, which, to her, is currently threatened by corrupt governance. Having grown up going to powwows and lodges surrounded by her tribal community, Rivera’s family and community have instilled a sense of the sacredness of the land and other people in her, which has given her the desire to protect and take care of those around her and the land she walks on. To her, the Dakota Access Pipeline, a crude oil pipeline that crosses sacred Sioux tribal sites and is at risk of polluting the tribe’s water supply, is one of the countless examples of the U.S. government remaining ignorant of Indigenous communities. Although Rivera believes increased leadership by Indigenous people would have a significant positive impact on the environment, she recognizes that not all Indigenous people have had the same community and environment-focused upbringing she considers herself lucky to have had. Thus, they might not put those values first in their leadership.

Beyond federal recognition, Rivera also believes that Indigenous leadership would advocate for environmental justice, which, to her, is currently threatened by corrupt governance. Having grown up going to powwows and lodges surrounded by her tribal community, Rivera’s family and community have instilled a sense of the sacredness of the land and other people in her, which has given her the desire to protect and take care of those around her and the land she walks on. To her, the Dakota Access Pipeline, a crude oil pipeline that crosses sacred Sioux tribal sites and is at risk of polluting the tribe’s water supply, is one of the countless examples of the U.S. government remaining ignorant of Indigenous communities. Although Rivera believes increased leadership by Indigenous people would have a significant positive impact on the environment, she recognizes that not all Indigenous people have had the same community and environment-focused upbringing she considers herself lucky to have had. Thus, they might not put those values first in their leadership.

“Are Indigenous people in power voting on behalf of the environment? Are they voting on behalf of women? Are they voting on behalf of elders and taking care of the community?” Rivera said. “I think what’s important is watching candidates’ voting trajectories and what they’re standing up for. I trust that Indigenous people, if they’re raised in an Indigenous community, have grown up understanding how important the environment is, but not every Indigenous person has that privilege.”

Similarly, Nijmeh says her background is influential in seeking government involvement, with her mother serving as the chairwoman of the council before Nijmeh’s election. Here, she remembers shadowing her mother at meetings when she was seven years old, watching her mother meet with members throughout the Bay Area to advocate for her people’s rights.

Today, Nijmeh has stepped into the role that her mother once held, both as the sitting chairwoman, and figuratively, as she continues to champion the rights of those within her tribe. In early August, she and other Ohlone Tribe members began their horseback journey from San Francisco to Washington D.C., dubbed the Trail of Truth, riding as a protest against the resistance that the federal government has shown towards recognizing the tribe’s sovereignty. Nijmeh, despite being frustrated by the lack of mainstream coverage, believes that the ride was a firm message of recognition and unity.

“It was for awareness of our story and our struggle, and the message is we are still here, and we’re not going anywhere,” Nijmeh said. “We’re not giving up. We traveled across the nation, visiting other recognized tribes and non-recognized tribes, and the other message was of unity — coming together to protect all our rights against the government because as the government continues to chip away at our rights when we come together, that would be less likely to happen.”

Despite hundreds of years of genocide and colonization, Native Americans, Alaskans and Hawaiians have survived, maintaining their community and fighting for a voice in the politics and governance that impact them directly. Nijmeh believes the recent uptick in Native involvement in politics — both in running and in showing up to the polls — has a distinct positive effect on the future of America’s political representation.

“Things are just getting started,” Nijmeh said. “People are starting to get interested in how they need to step into these leadership positions to represent people who look like them. Brown people, people of color — more of us are stepping into this. I think the young people are starting to realize that we need to represent our people, people who look like us, because white people don’t look like us, and they don’t have the same interests to protect.”