While hating vegetables is not an experience unfamiliar to children, Chinese teacher I-Chu Chang recalls holding a special grudge against the daily greens she’d eat. Since she was 9, Chang has detested not only the flavor and smell of vegetables, but their texture as well, like insects crawling and picking at her gums. Yet as an adult, Chang strictly adheres to a vegetarian diet, something to which she attributes positive mental and physical effects.

“After I became a vegetarian, I felt less stressed,” Chang said. “My stress levels went down drastically. I started to become more calm and I don’t get irritated easily compared to when I was not a vegetarian. And I really liked it this way, so I just stayed a vegetarian.”

Sophomore Michelle Lee relates to hating the cultural foods she was served during her childhood. Lee would reject cuisines and dishes that used peppers and spices since she associated spice with pain. The embodiment of her dislike was kimchi, a fermented cabbage that more often than not was too sour, too crunchy and too spicy. But now she appreciates the dish despite her initial hatred for it. Her attitude on trying new things has changed since her childhood, too. Lee adds that being exposed to a wider variety of cuisines and cultures will broaden one’s palate, allowing people to find greater enjoyment in foods that they previously hadn’t thought of liking before.

“People originally dislike things because it’s unfamiliar to them — at least that’s what it was like for me,” Lee said. “I feel like we perceive anything different than the norm as something we don’t like automatically, but I think that over time, with exposure, people will come to like things.”

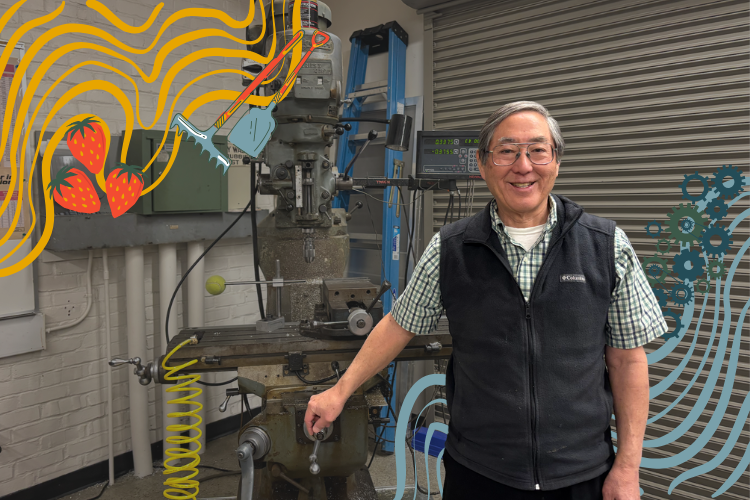

But for Engineering teacher Ted Shinta, picking between familiar and unfamiliar foods wasn’t an option. Having parents who immigrated to the United States during a time of economic depression, “no” was simply not something his family ever said to a plate of food.

“I think what really affected me was that my parents grew up during the Great Depression, the 1930s,” Shinta said. “They were taught never to waste any food. My mom said when she would eat rice, she would not finish the meal until every speck of rice was out of that bowl. They couldn’t leave anything behind. They kind of brought us up the same way, and also to eat whatever they served. Whatever they put on your plate, you have to eat it.”

Growing up, his parents would often feed his sisters and him traditional Japanese food, including okazu – a general term for side dishes – which for him often consisted of rice with fried pork and stir fried vegetables. During his childhood, he preferred American foods to traditional Japanese dishes, as people would make fun of his sisters and him for eating Japanese food. However, now that he’s older, Shinta wishes that he would’ve eaten more of his parents’ cooking rather than pushing for American food.

Growing up, his parents would often feed his sisters and him traditional Japanese food, including okazu – a general term for side dishes – which for him often consisted of rice with fried pork and stir fried vegetables. During his childhood, he preferred American foods to traditional Japanese dishes, as people would make fun of his sisters and him for eating Japanese food. However, now that he’s older, Shinta wishes that he would’ve eaten more of his parents’ cooking rather than pushing for American food.

Chang didn’t push for other cuisines, but she often tried to escape what most children couldn’t — a plate of vegetables. Despite her parents’ attempts, Chang just couldn’t bring herself to tolerate the food, which she found pallid, bitter and gross. However, after having a conversation with her mom, she realized that she had not understood the diversity in vegetarian food beyond just vegetables.

“Before I was a vegetarian, my mom was one, and there was this one time she visited and I didn’t know much about being a vegetarian, so I bought a plate of salad for her,” Chang said. “She laughed and said, ‘Do you think I’m a cow or something? Why do you give me a salad? There’s other vegetarian food and I need protein, I need good oil, and you’re just giving me salad.’ That’s when I realized people have misunderstandings about what it means to be a vegetarian. People don’t know what vegetarians eat, and from there I knew there were a lot more things that I could try.”

Whereas Chang disliked vegetables for their flavor, Shinta says his taste and preferences in food were partially influenced by the culture and society around him. Being one of the only non-white people in his school, Shinta says he often chose American fast food over his parents’ Japanese food as a way to conform to the people around him. However, looking back, Shinta wishes that he would have been more open to eating food of his culture and to learning about his culture in general.

“I should have been brought up with a little bit more of that Japanese cultural background,” Shinta said. “Once I got to my 20s, I could have taken Japanese in college. My sisters did, I didn’t, because it’s just too much work. But, like I say, in me, there’s a longing for that.”

Although Shinta may have missed a couple of aspects of his culture during his childhood, he still strives to rediscover it. During family gatherings, his sister encourages him to eat natto, a fermented soybean dish that he says he still has to hold his nose to eat due to the odor. While he used to be disgusted by its smell, Shinta finds himself more willing to try it out, even if just for the sake of his family. Now, he finds himself trying all kinds of foods, since he believes that being in an environment with vast cuisines and cultures helps him rediscover his — one bite at a time.

“There’s many different food options and so we really eat good out here,” Shinta said. “But I know in other places, the food options are a lot less and you really feel it. I think it’s a little different for you guys growing up, because you’re in a community that has a large proportion of minorities, and it’s a diverse community. It’s just nice to live here where we just take it for granted that all this stuff is available.”