Each year, APUSH students listen to a familiar lecture on using the term “enslaved person” instead of “slave” when speaking during discussions or writing essay responses such as Document-Based Questions. This practice isn’t unique to APUSH classes: many AP Literature and history teachers across MVHS give talks about inclusive and appropriate language.

However, junior Abhi Kotari, who is currently taking APUSH, believes that students lack sensitivity regarding their choice of language despite these lessons. He says this can be explained by the low diversity in MVHS’ demographics. Although MVHS has 92% minority enrollment, over half of the student body is Asian, meaning that the actual diversity of the student population within MVHS is diluted. Kotari believes that if MVHS were more diverse, students would be more careful with their language as they would be able to see the impact of their words.

“If you look at the terms ‘enslaved person’ versus ‘slave,’ we understand the reason for why we are using new words and see the difference,” Kotari said. “Right now, we can’t see the actual difference using the right language makes to a person of that community.”

MVHS alum ‘24 Meggie Chen also believes MVHS’ student demographic contributes to students’ lack of sensitivity or knowledge surrounding their language. Both Chen and Kotari believe that most MVHS students wouldn’t correct their peers if they were using language such as “slave” or “disabled person” instead of “enslaved person” or “person with disabilities.” Kotari believes that if he heard the outdated language in conversation, he wouldn’t even recognize that it was being used, while Chen says that if she were to notice outdated language being used in conversation, she doesn’t know enough about the topic to feel comfortable correcting someone else.

“In news articles, there are a lot of people with varying opinions on using labels like disabled person versus person with disabilities,” Chen said. “As someone who is neither disabled nor of African American ancestry, it feels strange to make a stance on these topics when I’m not even sure it’s correct. If I felt a little more educated about the topic, I could say, but I don’t want to say anything concrete when there’s a large diversity of opinions about the topic.”

Chen also believes her choice to speak up against the usage of a word is dependent on the situation she is in and the type of language being used. For example, correcting peers regarding their language feels different in a college setting where her peers are adults with more freedom, as opposed to high schoolers. She also believes the word “slave” does not have the same bad connotation as other words that have changed their meaning over time, like the “r-word.” The “r-word” was originally created as a medical term in the mid-20th century and has evolved since then to become a slur or used demeaningly.

MVHS seniors in AP English Literature are introduced to the ‘r-word’ repeatedly in the text “Flowers of Algernon.” Despite this, AP English Literature teacher Melissa Clark believes the addition of the book in the curriculum is extremely valuable because while MVHS students read books about people from diverse places, they don’t read a lot of books about diverse disabilities.

“Right before we started the text, we let the students know that there is some terminology in the text that can be a little jarring for us in our modern day setting,” Clark said. “But having them understand the history of the word is valuable because they understand why authors use it. It also has them understand that it’s not appropriate for us to use that word aloud during discussions, and they also should not be using that word while they’re writing about the text.”

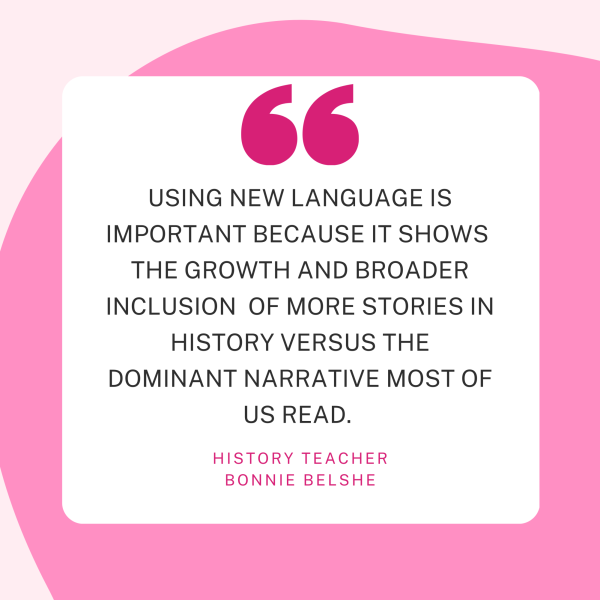

Belshe also believes that it’s important for students to understand the reason for a language shift, even if the outdated term may not be offensive. She implemented new and inclusive language following a technique called “reading against the grain,” where students recognize they are looking at the past as historians, acknowledging the changes in mindset that have occurred since then by using new language.

“Using new language is important because it shows the growth and broader inclusion of more stories in history versus the dominant narrative that most of us read — the very narrow slice of economically elite, politically elite and socially elite, which tends to be very white focused, male focused history — that was positioned for so long as the default history,” Belshe said. “When we only look at sources given in the language of which they are from — white supremacy — then we’re only looking at history through the lens of white supremacy.”

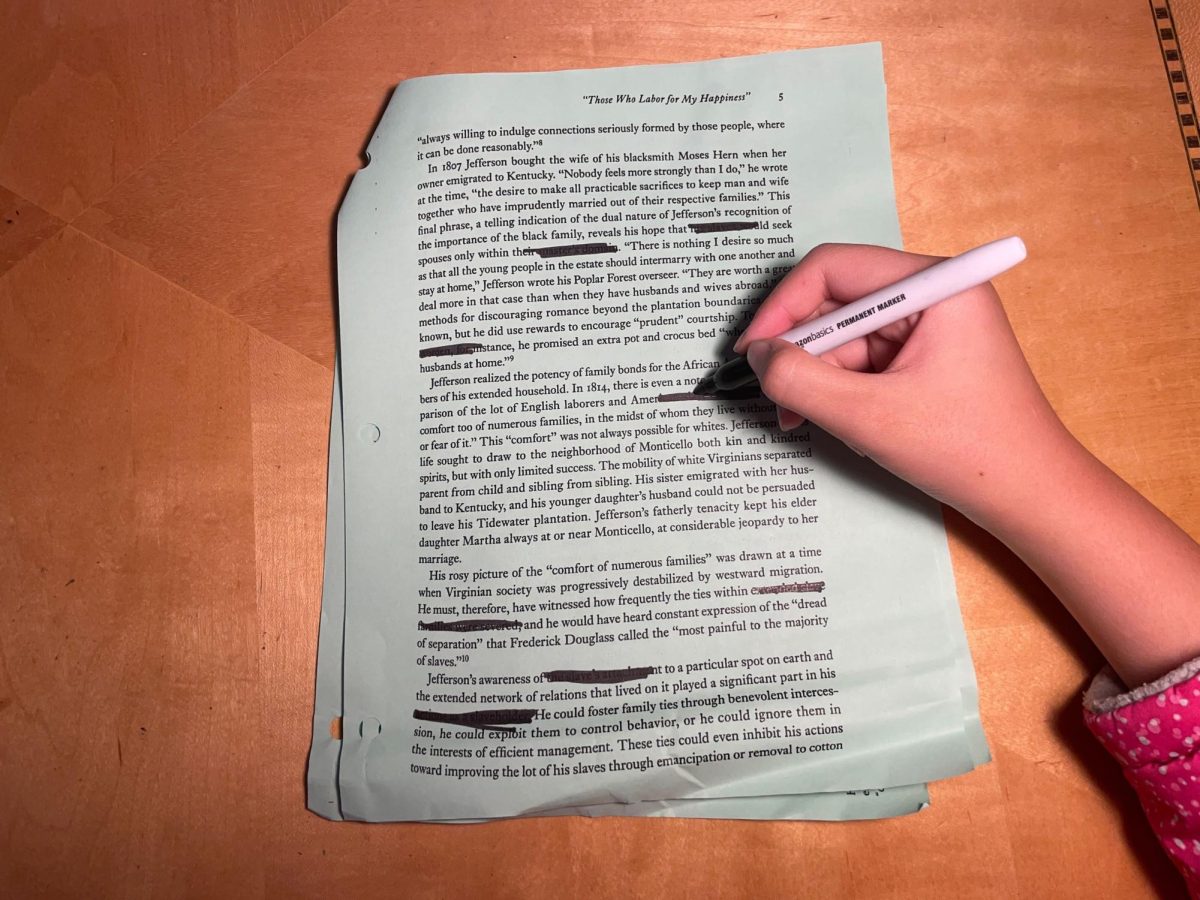

While Kotari understands the importance of using accessible language, he has found it difficult to completely change his language. Kotari says he often uses the wrong terminology, causing him to need to rewrite words in his essays. He attributes this difficulty adjusting to still constantly seeing the outdated language in textbooks and in media, which he thinks encourages students to continue using that language even if it’s morally incorrect.

Belshe agrees that media portrayal of language does affect its usage, especially among Gen Z and Gen Alpha students. As a result of the media’s influence on students, both Belshe and Kotari recognize that it can be difficult for students to change their language when the media they consume reflects outdated language.

“When using new language, it’s about the ‘know better, do better’ attitude,” Belshe said. “It doesn’t mean that we are all perfect with our language every time, but it’s important that we recognize the work that we’re doing to change. Once we recognize the continued reinforcement in the classroom is important, those changes outside of the classroom will start to come. If we have a new generation that can recognize this shift, other changes will come from there.”