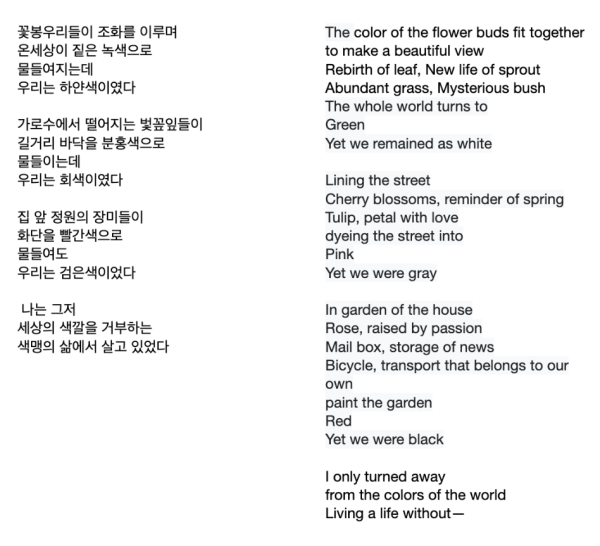

In the first La Pluma issue of the year, sophomore Subin Ko published “Timeline Now,” a piece that comes in two versions. Initially written in Korean, Ko later translated the poem to English — a process he repeated for “Color of the World,” his poem in the spring issue.

For some, translation can be necessary for communication in a new environment. Ko moved to the U.S. his freshman year and recalls relying on translation apps to read English poetry introduced to him by a friend. However, with the poems he later published in La Pluma, translation also became a creative endeavor for Ko, requiring artistic vision in its own right. Similarly, Drama teacher Hannah Gould, who has experience translating Russian to English, describes language as an art form that skilled translators can shape and manipulate.

“The first necessary layer of what makes a good translation is in-depth, focused and detailed, loving care toward nuanced meaning,” Gould said. “You have to be attuned to tiny little shivers of meaning that aren’t fully explicit, but that are there and that are important. You can’t be super efficiency-minded and economical and just focused on results. You need to be lovingly engaged in the process.”

However, this freedom comes at a cost, as translators must pick between an infinite number of possible ways to interpret any given text. While translating his poem into English, Ko often found himself sifting through a plethora of synonyms with almost imperceptible differences in tone. Ko feels most compelled to preserve the atmosphere of the work being translated, but senior Anqi Chen, who translates YouTube captions from English to Chinese, points out that first and foremost, the translation needs to be readable to serve its purpose to the reader. To Chen, creating an accurate translation can be a challenge in itself.

“You realize you don’t have an exact translation for a lot of words, so you end up needing to replace them with longer and more complicated things,” Chen said. “That makes the translation itself not that readable.”

Because of these hurdles, Chen finds that translated writing often sacrifices entertainment for accuracy, resulting in dry interpretations of the original work. Gould explains that while no translation can fully capture the meaning and nuance of the original, translated material is still worth reading and acknowledging.

“The purpose of translation is accessibility,” Gould said. “It’s the ability to make art knowable to people who might not have access to the original language for a million different reasons. I’ve heard people say, ‘I never want to read Russian literature because I know that there’s things missing from it, and I just want to read it in the original.’ Okay, well, but you’re never going to read it in the original, and if you’re not willing to read something in translation, then it’s just completely lost. Wouldn’t you rather have like a fraction of that meaning and that beauty than not at all?”

Gould attributes her interest in translated literature to her sophomore year of high school, which she spent reading translated Polish, Czech and Russian literature while studying in Poland. In college, she delved further into translated Russian literature and started learning Russian; her senior year thesis tackled translation, both between languages and from literature to film. Her first full-length translation came after she finished her master’s degree; it was also the first production she worked on for MV Drama, an adaptation of “The Marriage” by Nikolai Gogol.

“It was a play that I had performed in Russian before when I was in college, and at first I was like, ‘Oh, I know I want to do this play, but maybe I’ll just use someone else’s translation,’” Gould said. “And then I looked around at the translations out there and I was like, ‘Oh, no, these suck.’ And so then I forced my hand into translating it, which is good because it was so much work.”

Gould used the original play, an English version and two different Russian dictionaries to translate the script, a process that spanned a month of painstaking work every night after school. While Gould was proud of the end result, she has yet to revisit translating literature — the texts she has translated since are usually less intensive, such as choruses of songs, Instagram posts or signs.

Ko agrees that translation can be an arduous process, especially when it comes to poetry. He explains that differences in sentence structure can make it difficult to translate artistic features from Korean works into English, though conveying the intended feeling of the original work is certainly possible.

“I think everything can be translated, but I think there are things that we cannot make this whole text right into the translation,” Ko said. “Between English and other languages, each word has different meanings, and some words in other countries can evaporate, or English has more words related to this one subject. Because of that, how the sentence feels or how the words are laid down can be quite different. I think we can definitely translate the feeling of everything, but we cannot bring that whole structure into the other languages.”

Beyond communication, Gould explains that language is closely tied to culture, with the act of translation enabling speakers of different languages to come to a place of shared understanding. For instance, the verb “to have” isn’t used in Russian — instead, Russian utilizes terms for proximity, which Gould says could shape how speakers of the language think about the concept of possession.

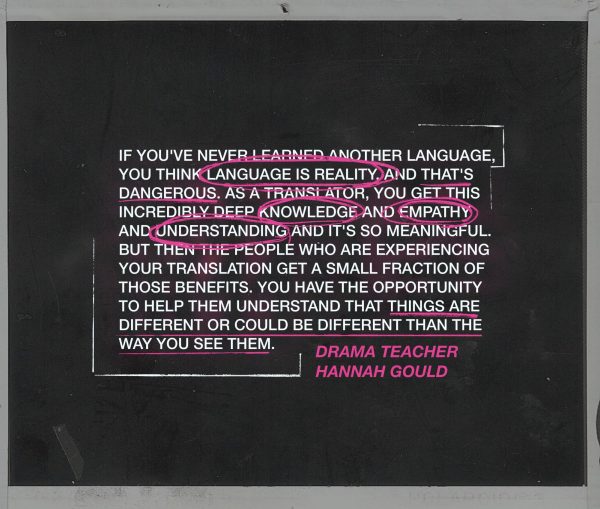

“If you’ve never learned another language, you think language is reality, and that’s dangerous,” Gould said. “As a translator, you get this incredibly deep knowledge and empathy and understanding and it’s so meaningful. But then the people who are experiencing your translation get a small fraction of those benefits. You have the opportunity to help them understand that things are different or could be different than the way you see them.”