The sudden blare of the alarms sets MVHS in motion as countless students file out of classrooms. The familiar procedure of a fire alarm is particularly stressful for Jenny Garver and Anagha Rao, two Santa Clara County Office of Education (SCCOE) special education teachers for a post-secondary program at MVHS.

The program is for special education students aged 18 to 22, and the students have different types of physical and mental disabilities. This makes it difficult for the teachers to safely evacuate their students. Garver and the instructional aides must transfer every student into their wheelchairs before wheeling them out of campus, one by one. Safely wheeling out the students isn’t the only challenge the teachers face; the fire alarms once shocked a student into a seizure.

“We have had bad experiences here with fire drills in the past when there wasn’t enough staff to get everybody out,” Garver said. “We had several bomb threats last year and then when they closed campus and told everyone to get out, we were like, ‘Wait, I don’t have enough staff to get everybody out.’”

During last year’s bomb threats, Garver’s class was unable to evacuate until an hour after the other classes had safely exited the school. As a result, they promptly voiced their concerns to the SCCOE district staff until more staff was provided. Garver and Rao constantly work to improve the SCCOE special education program and the quality of life of their students — for example, advocating for the installation of a doorstop because all of Garver’s students use a wheelchair and for a bathroom that suits their needs.

“I feel that advocacy is part of our jobs,” Garver said. “We have to stand up for our students, we have to advocate for what they need. It’s not always perceived positively by our own organization, but we have to do it because our students have rights, and we have to make people understand that. Sometimes we think we’re just here to teach, but we can’t really do our jobs as teachers if we’re not advocating for what they need, as far as staffing, bathrooms, eating and all of these other little things.”

According to SCCOE school board member Tara Sreekrishnan, the board’s top priorities include increasing the recruitment and retention of qualified staff, enhancing professional development and securing more funding. Garver and Rao both agree that funding would be beneficial for the classroom for a variety of reasons such as buying more snacks for the students or purchasing new equipment. When Garver first started teaching in California around twenty years ago, she recalled that the district provided over $1000 to spend on her classroom over the school year. Today, that amount has decreased to $350.

“Every special education teacher that I know spends thousands on their classrooms over the years,” Garver said. “We do it because we want them to have snacks to choose from, we want them to have different educational materials and things. So we just buy it for them.”

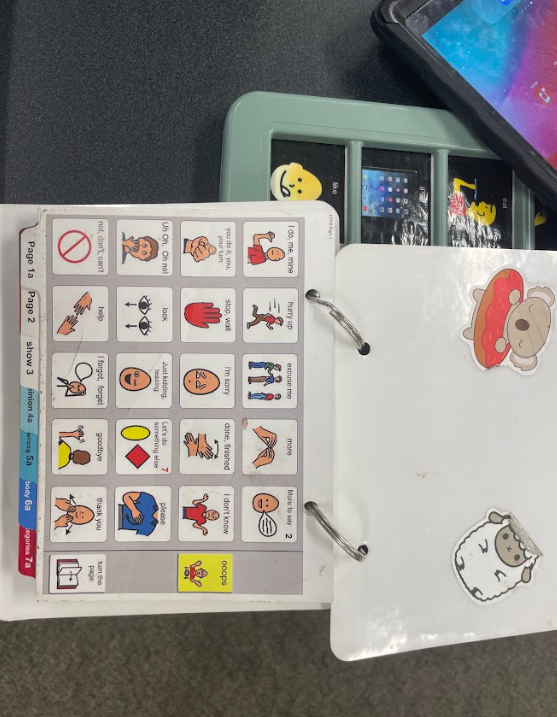

Although the teachers spend their own money to buy goods for the students, the SCCOE special education program buys all the necessary office supplies, including gloves and sanitary wipes. They also provide communication tools, which Garver and Rao’s nonverbal students have become accustomed to using. These include slips of paper with pictures on them which students point at to communicate their thoughts, electronic devices called GoTalks with voice messages that can be activated with the press of a button, iPads and more. However, students cannot take the communication devices that they’ve grown up using with them when they graduate.

“We know how to program these devices and what needs to be done, but it’s not the same with families because they already have so much going on,” Rao said. “Our students may not be able to do that by themselves completely after they turn 22. That feels like taking their voice away from them once they turn 22 because they have no more way of communication.”

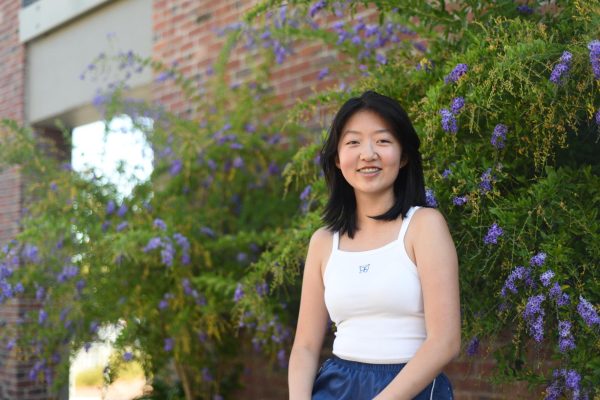

The development and use of communication technology is not the only thing that has improved their learning environment over the years. For example, use of restraints — physically limiting a student’s movement for the safety of themselves or their peers — are now highly monitored at SCCOE. Despite these advancements in their learning environment, students attending the special education program still face troubles when it comes to fitting in with their peers. Sophomore Shreeya Setty, who regularly stops by Garver and Rao’s rooms, believes that most other MVHS students don’t interact with the students from the special education program.

“It’s really sad because everyone has the opportunity to stop by because that room is open,” Setty said. “The students and staff in the classroom are really welcoming. They would love for people to stop by and say hi to their students. The students get really excited when they see students on campus who are not just enrolled in their program come by and say hi. It’s really as simple as a wave.”

Garver and Rao work at MVHS even though they are employed by SCCOE, not by FUHSD like the other teachers on campus. As a result, they note that they also have difficulties integrating into the MVHS environment although they have worked here for a year, explaining how being recognized by a student outside of her classroom is an unusual but appreciated occurrence. Garver recalled fondly how a few weeks prior, an MVHS student greeted her by name while walking by with his friend and how the small but uncommon interaction made her day. Setty believes the rarity of the action is a reflection on the MVHS community and their priorities.

“I don’t think people at the school may try to be extra welcoming or inclusive because I think they’re very focused on themselves on their education,” Setty said. “But it’s truly important to make sure everyone in our school campus feels included and feels like a part of the community at MVHS.”

Although Garver and Rao face many challenges from both outside and inside their classrooms, they love their jobs. Seeing their students smile, laugh at jokes and see their learning progress — no matter how small — makes it all worth it, according to Garver. The learning is not one-sided either; both Garver and Rao say they have learned many lessons from their students over the years.

“A thing I’ve learned in special education is that you always presume competence,” Rao said. “You never think they can never do it. You don’t assign that lack of ability to someone. You never know what someone is capable of, not just in special education, but in general and to yourself as well. Presuming competence from everyone in everything has been the biggest thing that I’ve learned.”