Delving into two Chinese families in Cupertino — the Huang family and the Gao family, we uncover why they immigrated to the U.S. Affected by major events in China such as the Cultural Revolution, a political uprising from 1966 to 1976 led by the Chinese Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong, these families detail their search for freedom.

SHI TONG HUANG’S FAMILY HISTORY

When Le Hao Huang was in his late teenage years, he moved from Guangdong, China to Indonesia to make a living for himself when his parents could no longer support him. During the 19th Century and early 20th Century, laborers from China traveled as indentured servants to various places across the world, such as the U.S. and Indonesia. Cupertino resident and grandson of Le Hao Alex Huang recounts Le Hao’s experience as one of those laborers.

“The people who went are considered piglets, as when you go over, they take all your papers and you owe them a huge amount of money you have to pay off, so you’re basically an indentured servant,” Alex said. “My grandfather worked on the farm most of the time and he was able to pay off his debt. From there, he started going out to sell tofu and then moved to having a grocery store – he worked hard.”

Le Hao met his wife, who also immigrated from China, in Indonesia. They had four children, the youngest of the four being Alex’s father, Shi Tong Huang. Once China was liberated from Japanese occupation in 1945, Shi Tong’s mother wanted to move back to China for educational opportunities, so 6-year-old Shi Tong and his family packed up and made the journey back in 1949.

Although Shi Tong started attending college after he returned to China, his education was halted once the Cultural Revolution started. He says that people like him who were pursuing an education were sent to farms to work since people believed that those who had education didn’t understand the hardships of farmers and other laborers.

Afterward, when the revolution ended, Shi Tong was able to fare better than others because he had a couple years of college under his belt, and became a chemistry professor. He also married Qi Jie Yang through a matchmaker, and had two children – Alex and his younger sister, Melissa Huang. When the chance to move to the U.S. arose however, Alex says that his father was inclined to choose that path despite already having a career.

“[My parents] went through a 10-year stretch where people were not educated,” Alex said. “They didn’t know when [the government] would take that away again. For my parents, it was more important to leave that because there was no freedom or justice in that system. It wasn’t about coming here and having some sort of promotion in their career. It was more about coming to a place where there might be better freedom and education for their kids.”

Shi Tong uprooted everything he knew in hopes of a better life for himself and future generations, and moved to the U.S.

QI JIE YANG’S FAMILY HISTORY

In the early 20th Century, Yang’s mother was brought over to Sacramento, California as a servant girl to a Chinese grocery store owner’s second wife. According to a Chinese marriage custom, families that were well off had to find a servant girl to accompany their newly wed daughters, and Yang’s mother was picked for this role. However, since she didn’t have the documents to enter the U.S., a U.S. birth certificate was forged under her name, stating that she was the grocery owner’s daughter; this also allowed her to gain birthright U.S. citizenship. Yang’s mother lived in the U.S. with the grocery store owner and his wife for a few years, but had to move back to China due to the grocery store owner’s gambling addiction, as it had landed him in a lot of debt.

At that time, China was under Japanese rule, and it wasn’t until Yang was born when China became independent. After the liberation, Yang had the choice to move to the U.S. with her uncle, but chose to remain in China since her family was well off and could possibly prosper in the wake of new opportunities. While in China, Yang became the fifth daughter in her family to be accepted to college, which was rare for women in China at the time. Unfortunately, she was barred from going to college once the Cultural Revolution started. As the treatment towards those who were educated and well off worsened, she searched for freedom by trying to find a way to leave China.

“My mom decided she was going to swim to Hong Kong, which was not under Chinese rule,” Alex said. “She was practicing how to swim in the river because she had to swim through a channel to Hong Kong. Her brother learned of this plan and they decided that her brother would go instead. They had to have a map and the calculation of the tides so that they could swim with the tide instead of against it and he actually swam past the channel to Hong Kong.”

After Yang’s younger brother arrived in Hong Kong, he registered as a refugee and moved to the U.S. to study at the University of California, Berkeley. Later, his parents moved over from China to the U.S. to reside with him. Due to the illegal reassigning of the birth certificate to Yang’s mother, her U.S. citizenship allowed her to bring over Yang, Shi Tong, Alex and his younger sister, Melissa Huang.

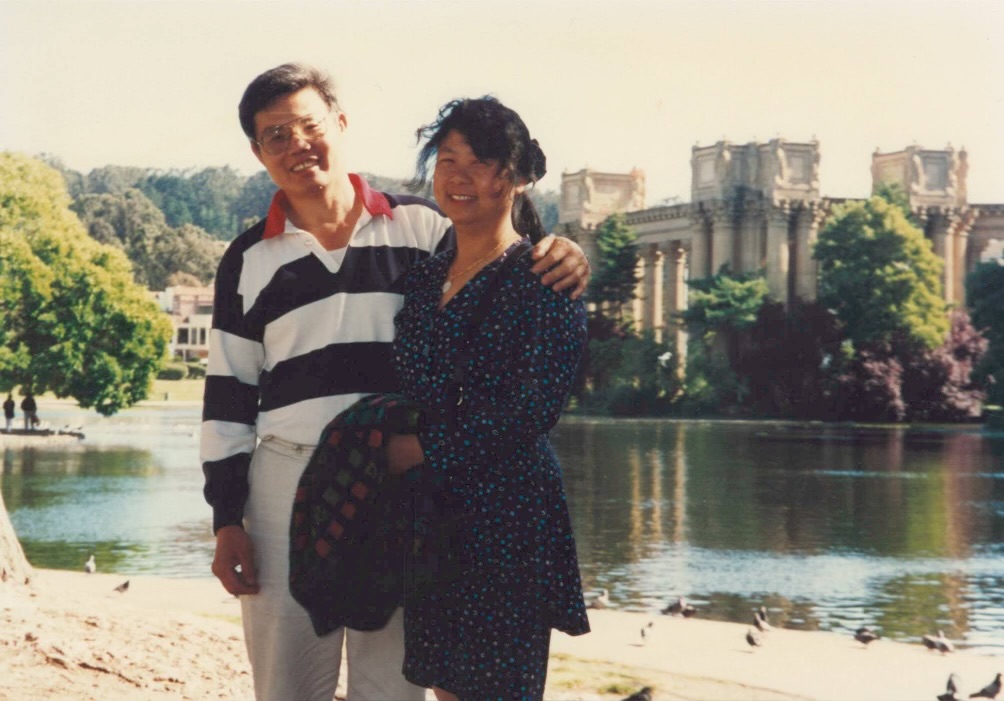

THE HUANG FAMILY’S ARRIVAL IN THE U.S

The Huang family arrived in the U.S. on Aug. 24, 1982. Shi Tong and Yang spent most of their time working multiple jobs at a plastics manufacturing company and hotels to provide for their children.

While their parents were trying to make ends meet, Alex and Melissa also took on various part-time jobs. Melissa was employed as an arcade manager, and Alex was hired for a variety of jobs, such as passing out fliers on the streets of San Francisco while wearing costumes and teaching people how to use Adobe PageMaker. One of his most memorable moments working a part-time job was as a dishwasher at a French restaurant.

“The first day I was there, they told me what to do, but I must’ve forgotten because there was a lot of stuff to learn,” Alex said. “In French cuisine, there’s a meal called escargots, and as a dishwasher, I was supposed to clean off the dishes and I threw away all the shells. Later on I learned that in the escargots, the shells are actually bought. That’s why there were nice, beautiful shells and I was supposed to save them, and they would wash it and boil it and then they would stuff it with the snail meat and butter again and that’s how they make it — it’s not actually a live snail.”

BRIDGING THE PAST AND PRESENT

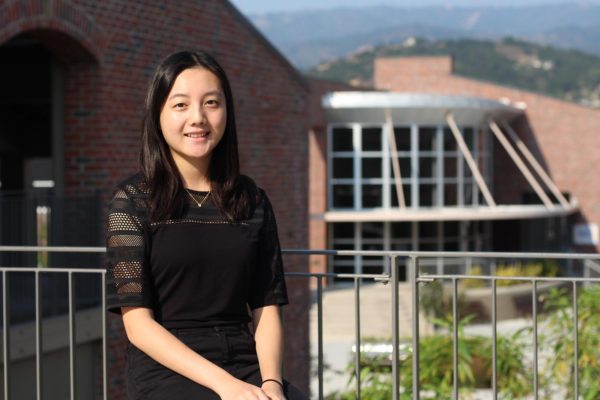

Like the Huang family, senior Olivia Gao says that her parents also chose to immigrate to the U.S. due to more freedom. Gao recently found out that she was born under the one child policy in China, which was enacted by the Chinese government from 1979 to 2015 restricting families to only having one child. In addition to her dad completing a masters degree at Texas A&M, Gao says that having another child was one of the main reasons why her family moved to Texas in 2008, where her younger brother was born.

Although she lives halfway across the world from her relatives in China, Gao says that her parents often tell her to reflect upon her grandparents’ experiences and the great lengths they went to in order to survive during the Cultural Revolution, such as eating solely sweet potatoes and even tree leaves when food was scarce. However, with both a language barrier and a different environment where they grew up, Gao says there is still a disconnect between her and her family in China.

“One thing that still continues to affect my family is the generational gap between me and the older generation,” Gao said. “Obviously, they were the ones who lived through and stayed in mainland China during the revolution, so they supported Chairman Mao [Ze Dong]. Because I live in a more progressive area in California, there are lots of disagreeing opinions and thoughts that I don’t necessarily agree with, but I nod along anyway.”

Even with generational differences, Shi Tong finds it vital to tell family stories to younger generations to show a family’s roots and pass on important values.

“Compared to people who haven’t been through the Cultural Revolution, it would be difficult for them to see why it is important to maintain the freedom of choice because it’s already given to them,” Shi Tong said. “For people who haven’t experienced it, it’s very important to go back and learn history and understand how it was very limited back then. It’s important to go back and look at that to understand where you are at now, it’s very precious, it’s not something to be taken for granted.”