In the World Studies classroom at MVHS, students hide giggles at sensual descriptions and scenes in “Like Water for Chocolate” by Laura Esquivel. The novel is taught during a history unit focusing on revolutions around the world, including the Mexican Revolution, the same period in which the events of the book take place.

“Like Water for Chocolate” is part of the magical realism genre, in which magical or supernatural elements are incorporated into a real-world setting. Popularized by Latin American authors from the 1950s to the 1970s, the genre is home to Latin American bestseller “One Hundred Years of Solitude” by Gabriel García Márquez and international classics such as “Beloved” by Toni Morrison and “The Metamorphosis” by Franz Kafka.

While “Like Water for Chocolate” is part of the magical realism canon, it ultimately plays into the problematic stereotypical portrayals of Latinas, and intentionally paints these characters as “inherently promiscuous,” “dramatic,” “fiery” or “hot-headed.” Aside from being emotional, the main character Tita is repeatedly portrayed as a curvy woman with sexual descriptions of her generous breasts. Tita’s sister Gertrude joins a brothel, playing into hypersexual stereotypes, but she also fights in the revolution and subverts stereotypical gender roles. Both Tita and Gertrude play into many cultural expectations and stereotypical portrayals, yet they also subvert them in some instances. Thus, to truly understand their motives, readers must discard the stereotypical narrative and predominantly consider their intersectionality.

While “Like Water for Chocolate” is part of the magical realism canon, it ultimately plays into the problematic stereotypical portrayals of Latinas, and intentionally paints these characters as “inherently promiscuous,” “dramatic,” “fiery” or “hot-headed.” Aside from being emotional, the main character Tita is repeatedly portrayed as a curvy woman with sexual descriptions of her generous breasts. Tita’s sister Gertrude joins a brothel, playing into hypersexual stereotypes, but she also fights in the revolution and subverts stereotypical gender roles. Both Tita and Gertrude play into many cultural expectations and stereotypical portrayals, yet they also subvert them in some instances. Thus, to truly understand their motives, readers must discard the stereotypical narrative and predominantly consider their intersectionality.

The book is similar to Zora’s Neale Hurston’s “Their Eyes Were Watching God,” which is taught in both American Literature courses and has been both criticized and praised for its portrayal of gender and race. Similar to “Like Water for Chocolate,” Hurston’s portrayal of the protagonist, Janie, navigates the intersectionality of her identity as a Black woman. Both of these books explore women of color’s self-actualization, and desire for sex.

To understand the complexities of such books, students must be equipped with knowledge of race and gender stereotypes and be prepared to approach sexual encounters in the books with maturity. They also must be able to identify the role cultural traditions play in characters’ motivations. This becomes especially important in books where characters represent marginalized communities, such as Black and Latina women, as they have been historically hyper sexualized.

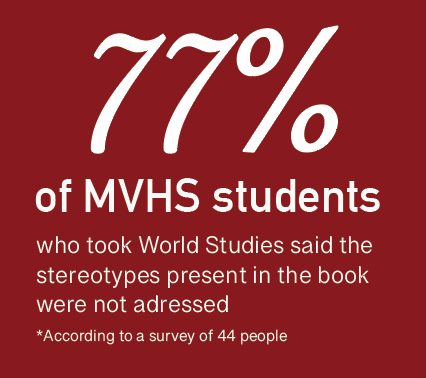

While MVHS does have a diverse literature curriculum, there is always room for improvement. “Like Water for Chocolate” fits the needs of both the history and literature subject matters of the World Studies unit, but stereotypes and intersectionality must be part of the conversation. “Like Water for Chocolate” has the potential to teach students to think critically about the intersectionality of gender and race before taking an American Literature course their junior year, but to do so, teachers must teach in-depth and critical lessons on how to navigate the complex use and subversion of stereotypes.

Teaching a racially and culturally nuanced book without equipping students with the proper tools only proves to be harmful. The World Studies curriculum must either begin to incorporate critical lenses — such as the ones introduced in Honors American Literature — to fully understand “Like Water for Chocolate” or remove the book from the curriculum altogether to stop perpetuating stereotypes that impact the Latino community at MVHS.