The moment Melisa Lu set foot in Lynbrook High School as an English teacher, she knew she was going to love her job. As a child, Lu found school to be an unengaging, tedious chore. She often wished she could be back in the comfort of her home, doing something that actually made her happy: watching anime. Now, she had a specific goal in mind: to implement diverse media such as anime into her theme-analysis curriculum, giving students an opportunity to enjoy the learning process in a way she had never gotten the chance to.

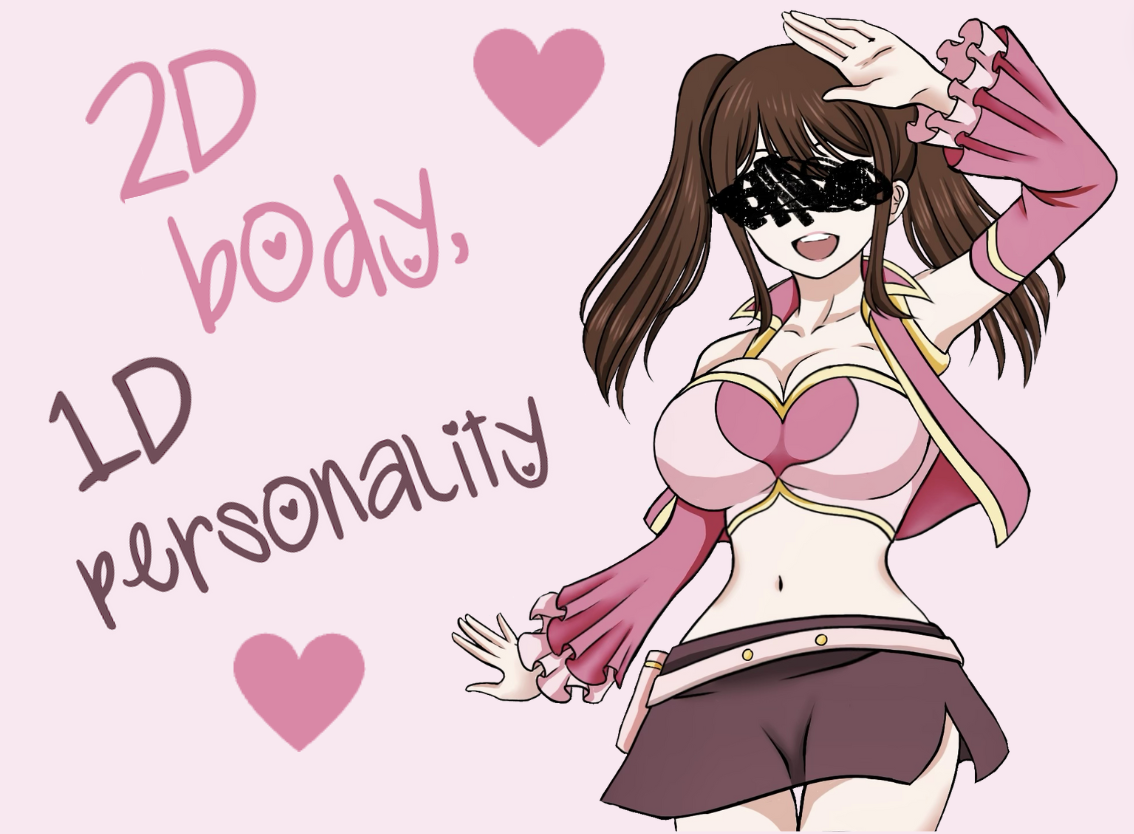

As much as Lu loves and appreciates anime, she admits there are times when anime is hard to watch. She has often found herself extremely disgusted by the sexualization of female characters, especially through interactions with male characters. Lu describes herself as almost jaded about it. Now, when she does see fan service — sexual material intentionally added to please the audience — Lu says she simply rolls her eyes or stops watching the anime entirely.

“Female characters tend to get less screen time or else they get power-ups off-screen,” Lu said. “It’s thoughtlessly reducing female characters to only their love for a male character or their role as a love interest, either equal to or overpowering their role as a hero. These tend to be very big defining traits of female characters that aren’t as prominently seen in the male characters.”

MVHS English teacher Shozo Shimazaki says sexualization dehumanizes girls and women. Shimazaki has a teenage daughter of his own and worries that anime may indoctrinate audiences with stereotypes about certain genders, implicitly sending the message that the male perspective is more important than the female one.

“I have brought this up with my daughter, too,” Shimazaki said. “A lot of anime imagery objectifies certain body parts of women. There are these moments, like in ‘Demon Slayer,’ where there is a scene about a character who does objectify women from that character’s point of view. It’s not necessary — it’s inappropriate and very male-centered in point of view. That part of it, as a father, I don’t like.”

Sophomore Christopher Lamfalusi has also noticed many instances where female characters are portrayed as “horny” and in need of protection, whereas males are depicted as “manly studs.” Having started his anime journey watching “Naruto” at an elementary school sleepover, Lamfulusi has become increasingly familiar with the disproportionate female bodies and skimpy clothing that he explains are practically trademarks of many anime.

“It’s to appeal to their audience,” Lamfalusi said. “Young boys are like, ‘Oh wow, it’s a guy with a ton of girls around them’ because that is a stereotype of what a guy wants. Sexualization appeals more to a male audience, especially younger men and boys.”

Lamfalusi is most familiar with shonen anime, which he says is a style of anime that caters to a young male demographic with action-packed fight scenes and harrowing adventures. On the other hand, shoujo anime is a genre made for a female audience according to . Often mistaken for the slice-of-life genre, shoujo mainly focuses on young girls’ journeys through growing up, forming relationships and exploring the emotions of heterosexual romance. Lu considers modern shoujo to be an interesting type of anime to watch and analyze, as writers and illustrators of shoujo are typically female, just like the characters they create.

“Over time, as discussion and discourse about female representation, portrayals, roles, relationships and romance have evolved, they’ve expanded a lot more,” Lu said. “You will still have shonen and shoujo that are focused on romance, with a love interest or female characters who are weak and trying to get stronger, but there has been a lot more variation, a lot more awareness and intentionality, about how we’re constructing these narratives.”

One factor Lu feels contributes to the overarching male domination of anime is women’s complex role in Japanese history. In particular, Lu points to geisha — women and young girls who would serve and entertain men, performing traditional Japanese arts and hosting in teahouses. Sometimes, the girls were forced to perform sexual services for clients in the form of indentured servitude, and were considered by many to be prostitutes. Lu notes the similarities between geisha women trapped in the patriarchal society of Japan and female anime characters, who only exist within narratives created predominantly by males.

Lamfalusi muses that to many people watching anime, the objectification of women likely goes unnoticed or dismissed as a simple quirk of the show. After he realized how ubiquitous it is, Lamfalusi now sees sexualization and objectification as grotesque. He hopes to see a change in the anime industry soon.

To Lu, “My Hero Academia” is a relevant case study of sexualized female characters due to the creator’s art style. She finds that Kohei Horikoshi, the writer and illustrator of the manga version of “My Hero Academia,” commonly draws female characters with a primary focus on their butts, hips or breasts, objectifying them. However, Lu says such depictions are nothing she hasn’t seen before, and mentions that even through layers of sexualization, it is possible to find a silver lining. Lu mentions that in certain cases in “My Hero Academia,” as well as in other anime, she is able to overlook an anime’s sexualized character design provided the characters harness their appearances in an empowering way, whether through strength, confidence or ability to achieve their goals.

“I very much appreciate when female characters are owning their sexuality,” Lu said. “They use it as a form of power in their sense of self, in their identity. There is a difference between being sexual and being sexualized.”