“OnlyFans detected, opinion rejected,” reads the top comment on a young woman’s relatable Instagram Reel about backpacks. The implication of the comment is not hard to discern: something about the short video has convinced a slew of commenters that she is an OnlyFans model. Despite not actually being one, her joke is ignored by the video’s viewers, and her presumed lifestyle, criticized. “Women ☕,” reads the comment underneath, as though part of an inside joke against women as a whole, making fun of them for being stupid. The affected demographic of these derogatory, unoriginal comments are nearly always women, some as young as teenagers, who are regularly on the receiving end of casual misogyny.

Virtual misogyny is only the most recent incarnation of prejudice against women. Jokes at the expense of women are nothing new. For example, “boomer humor” infamously designates wives as nagging pests: fat, irritating, bad at cooking and stifling the men in their lives. “The old ball and chain,” a disparaging term for one’s spouse which once starred in wife-hating jokes, has evolved with the sentiment taking the form of comments bashing “women ☕.” On the internet, men — and some women too — blast women in their lives for their stereotypically feminine interests, lauding the usefulness of manly interests over the likes of pop music, chick flicks, fashion, diets and makeup. Meanwhile, women who are seen as too masculine end up targeted by transphobic commenters, even if they aren’t actually transgender.

In media aimed at diverse audiences, girls are sometimes seen as intelligent only if they can cleave themselves from such feminine pursuits, such as makeup, which are often demonized as vapid and shallow. “Harry Potter’s” Hermione Granger was a strong, smart character who scoffed at the series’ girly girls — the types of characters who were made to be fundamentally different from her and would never achieve the same level of popularity or respect. When millions of young girls read the books or watch the movies, Granger’s positive lessons of cleverness and achieving anything are distanced from femininity through her disgust with all things girly.

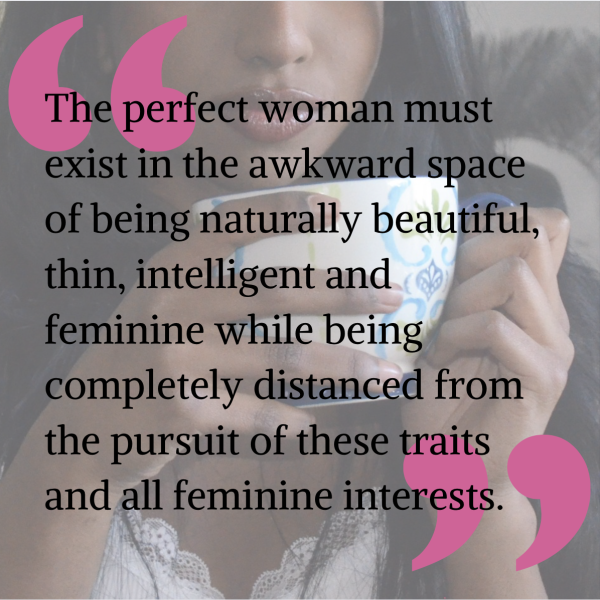

At the same time that femininity is scorned in popular media, deviating too far from the norm of thin, cisgender, conventionally beautiful and often white womanhood perpetuates a dichotomy where women are at once afraid to be seen as too feminine and thus stupid, or not feminine enough and thus unappealing. Invalidating common “girly” interests leads to shame and internalized misogyny, as girls are taught their interests make them seem vain and unintelligent. Girls may reject feminine interests to distance themselves from the typical woman to show they don’t try too hard. When done to gain male acceptance, they are subsequently mocked on social media for being “pick-me girls.” Thus, the perfect woman must exist in the awkward space of being naturally beautiful, thin, intelligent and feminine while being completely distanced from the pursuit of these traits and all feminine interests. America Ferrera’s Gloria said it best in “Barbie:” “You have to be thin, but not too thin. You’re supposed to stay pretty for men, but not so pretty that you tempt them too much or that you threaten other women because you’re supposed to be a part of the sisterhood. It’s too hard! It’s too contradictory and nobody gives you a medal or says ‘Thank you!’ I’m just so tired of watching myself and every single other woman tie herself into knots so that people will like us.”

At the same time that femininity is scorned in popular media, deviating too far from the norm of thin, cisgender, conventionally beautiful and often white womanhood perpetuates a dichotomy where women are at once afraid to be seen as too feminine and thus stupid, or not feminine enough and thus unappealing. Invalidating common “girly” interests leads to shame and internalized misogyny, as girls are taught their interests make them seem vain and unintelligent. Girls may reject feminine interests to distance themselves from the typical woman to show they don’t try too hard. When done to gain male acceptance, they are subsequently mocked on social media for being “pick-me girls.” Thus, the perfect woman must exist in the awkward space of being naturally beautiful, thin, intelligent and feminine while being completely distanced from the pursuit of these traits and all feminine interests. America Ferrera’s Gloria said it best in “Barbie:” “You have to be thin, but not too thin. You’re supposed to stay pretty for men, but not so pretty that you tempt them too much or that you threaten other women because you’re supposed to be a part of the sisterhood. It’s too hard! It’s too contradictory and nobody gives you a medal or says ‘Thank you!’ I’m just so tired of watching myself and every single other woman tie herself into knots so that people will like us.”

When the internet and social media creates a culture where women are mocked for their behaviors by both men and women, misogyny — internalized or not — follows closely behind. As teenagers, the high school years of our lives are some of the most formative. Our constant exposure to the internet, pop culture and even friends or family members have a powerful impact on our worldview, and being regularly battered by casual sexism while we’re most receptive to it can shift our outlook on what we consider to be acceptable jokes and behavior.

Validation and peer pressure can be deceptively strong social factors, and when we see the people or media we surround ourselves with peddling problematic ideas, it’s hard to not go along with them. It’s even harder to not turn around and spread the same rhetoric, becoming a bigger part of the problem. Comments like “women ☕” rarely appear in isolation, and to a male reader, they reinforce being part of a superior group and having an immunity to foolish, womanly mistakes. Consequently, to a female reader or content creator, receiving comments like these emphasizes a feeling of degradation, making it harder for teenagers who are being influenced by misogynistic ideals to develop more self-awareness and dismantle them before they fester. Lacking the courage to stand up to or ignore such rhetoric, teenage girls who experience misogyny may simply internalize it and sometimes even turn it back on other women around them.

Combating the issue of misogyny on social media and in popular culture is multifaceted and has no clear road map. When coming face-to-face with misogyny, it’s important to recognize it in its various forms. We must be vigilant in identifying and challenging these attitudes, whether they come from outside or from within, and whether they are overt or subtle. Before engaging with people on social media, or taking in media in general, examine it. Misogynistic comments, online or in person, can have disastrous effects and must never be treated as a joke. Truly, the saying must be “sexism detected, opinion rejected.”