The California Department of Education published a revision of the California Mathematics Framework (CMF) on July 12, 2023 to “offer guidance for implementing content standards,” according to the California Department of Education’s website. It influences policies in school districts and serves as a guideline for textbook manufacturers.

The CMF was written by a team of five: Jo Boaler, a professor at Stanford University; Katy Early, an instructor at CSU Chico; Ben Ford, a professor at Sonoma State; Jenny Langer-Osuna, an associate professor at Stanford University; and Brian Lindaman, a professor at CSU Chico.

The drafting process was overseen by the Mathematics Curriculum Framework and Evaluation Criteria Committee (CFCC), which was made up of 20 mathematics instructors and education professionals.

MVHS Math Department Lead Kathleen McCarty says she and the other FUHSD Math Department Leads are planning on reviewing it via monthly meetings. The first took place on Oct. 19 with District Math Curriculum Lead Jessica Uy and Assistant Principal Brian Dong.

“Right now, we’re just trying to understand what this giant document’s saying,” McCarty said. “And then there’s the whole connection we need to do between, ‘OK, what’s there? What are we doing? Are there changes that we want to make? Are there changes that are appropriate?’ We’re still answering that. We have this huge question mark over our head.”

The CMF aims to increase math proficiency — only 33% of California students met or exceeded state math proficiency standards in 2022, and there are achievement gaps for Black, American Indian or Alaska Native and Latino students.

However, Brian Conrad, a professor of mathematics and the Director of Undergraduate Studies in Math at Stanford University, thinks the CMF is heavily flawed. After reading drafts of the new revision, he wrote extensively about his concerns, including an opinion essay in The Atlantic. For instance, Conrad says an earlier draft of the CMF attempted to back its arguments by citing studies that actually contradicted the arguments, such as a 2013 study on approximate number systems and their impacts on complex math skills in adults, which the CMF misleadingly claimed was conducted on students. The Framework also mentioned “brain communication” when there had been no brain imaging involved in the study.

“It’s outrageous that nobody was held accountable for this,” Conrad said. “You have a team of five writers — somebody’s responsible. Why did the board not determine who is responsible to make sure that whoever’s responsible will never again be involved in setting public policy education in the state?”

Although Conrad acknowledges that nearly all the citation misrepresentations were fixed in the final version of the 2023 CMF, he still believes the problems they caused have not been fully resolved.

“I’m not claiming they fixed the citation misrepresentations throughout the entire document, because I told them, ‘Given the vast scale of this dishonesty, you can’t trust anything cited in this paper, so you’re gonna have to treat this like an academic treatise and check all of the citations,’” Conrad said. “And they didn’t.”

Citation misrepresentations aside, Conrad does not believe the CMF will help achieve its goals, calling it “bloated, poorly organized and lacking in substantial details” — a sentiment echoed by McCarty.

“Overall, the CMF is not easy to read,” McCarty said. “The Framework’s messages are interesting, but they’re vague. Most math teachers want to know specific examples. How do you do this? How would I move this into my classroom?”

The CMF hesitantly proposes removing Algebra II or Precalculus as prerequisites for AP Calculus, in order to increase mathematics proficiency and decrease inequality. It argues that Algebra II repeats many Algebra I topics, and Precalculus repeats many Algebra II topics, so the new requirements would allow students who have not taken said high school-level courses in middle school to take AP Calculus before graduating.

In earlier drafts, the CMF went further, advocating for a pathway in which “data science” courses replaced Algebra II. After severe backlash from an open letter signed by over 440 academic staff at California colleges and universities, including Conrad, the pathway was cut from the final version of the CMF. Conrad and other instructors claimed the “data science” courses were more like data literacy courses, and therefore could not replace Algebra II. Conrad says that without taking an Algebra II course in high school, it is “essentially impossible” to pursue a major in college related to careers in fields such as artificial intelligence, machine learning and data science.

MVHS class of ‘22 alum and Stanford sophomore Devin Gupta, who is double-majoring in physics and management science and engineering, says the math education he got at MVHS, which consisted of Algebra II/Trig, Precalculus Honors and AP Calculus AB, did not adequately prepare him for college.

“When you get to college, you do a lot of proof stuff, like rigorous derivation, that I don’t think high school courses you prepare well for,” Gupta said. “I would have had a better experience in college had I been prepared with more rigorous mathematics, specifically in rigorous proofs.”

However, the CMF discourages tracking students into different levels of math courses, saying it worsens inequalities, although it acknowledges that it can at times give students “high-quality instruction geared to their needs.”

Conrad points out that the first draft of the new CMF cited the controversial policy of removing Algebra I as a course option in middle school, adopted by the San Francisco Unified School District in 2014 in an attempt to decrease gaps in mathematics achievement along racial lines.

While SFUSD saw a general increase in the number of students taking advanced math courses across all ethnicities, the overall gap between low-income students and non-low-income students actually grew in terms of standardized test scores. According to Conrad, the reference was removed in later drafts of the CMF after a recent working paper from Stanford researchers indicated the policy was a failure.

Gupta, on the other hand, believes the education system should readily allow students interested in math to take higher level courses.

“There’s a lacking in our education system that is trying to cater its math curriculum towards everyone, rather than catering it to those people who really, really want to excel in math,” Gupta said.

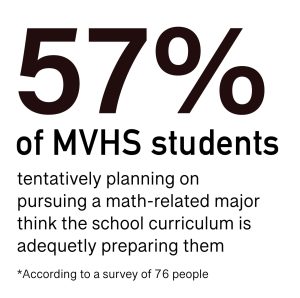

For MVHS and the district overall, it is still too early to draw a conclusion about the impacts the Framework may have, according to McCarty. She says that ultimately, FUHSD aims to meet the needs of its community. As of now, she doesn’t think it is likely that any major changes to the curriculum will occur due to the CMF.

“I think that here at Monta Vista, we’re doing a decent job with our foundational classes and our honors and AP classes,” McCarty said. “I don’t see us all of a sudden deciding to get rid of everything that we’ve developed so far.”