The American Dream

Examining the immigration stories of MVHS parents

April 14, 2023

Cupertino is a community built on immigration, an amalgamation of people from different backgrounds and places all drawn to Cupertino because of their desire for a better life. In this story, we examine the immigration journeys of three MVHS parents — learning what they decided to sacrifice and what they stood to gain.

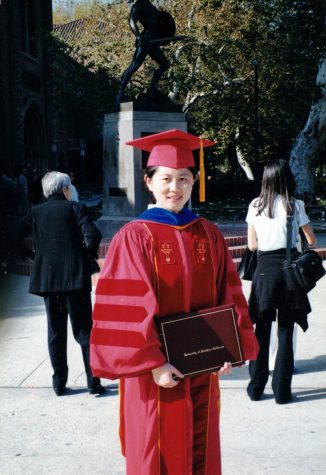

Tong Zhang

Before MVHS parent Tong Zhang decided to immigrate to the United States, she was faced with the decision of either accepting a faculty position at Tsinghua University, where she was getting her master’s degree at the time, or pursuing her PhD in the U.S. To others, taking the faculty position seemed like the obvious choice — she would be guaranteed a life of success and stability — but Zhang wasn’t so sure. She felt that by staying in China, she could envision her whole life laid out ahead of her, and she felt like she was relinquishing her only chance to experience a new world. With that in mind, she began the long and arduous process of chasing her dream of living in the U.S.

The first step was to be admitted to a PhD program in the U.S. Zhang knew she wouldn’t be able to afford to study in the U.S. unless she received a full scholarship. In addition to submitting applications to a variety of colleges, she also cold emailed professors and told them about her research as a student in China in hopes that someone would both say yes and provide her with a scholarship. After many emails, the University of Southern California responded to her with an opportunity to study there for free, provided that she worked as both a teacher’s assistant and research assistant. She accepted.

Zhang then had to find a way to physically travel to the U.S. Other than the process of getting a student visa requiring her to collect stamps from several different Chinese embassies, she also had to buy a plane ticket, which, at the time, cost five thousand dollars — equal to 10 months of her salary in China at the time. It was a costly decision, but Zhang ultimately decided to take it, and after a long and nauseating (it was her first time on a plane) flight with two layovers, Zhang landed in the Los Angeles International Airport with 200 dollars in her pocket.

Zhang remembers facing multiple culture shocks after landing in the U.S. The first time she entered her dorm at USC, she immediately called her mom to gush about the plush red carpets in her bedroom — she had never lived in a room with carpet before. She also remembers being shocked by her friends buying bunches of bananas at the supermarket: in China, they only ever bought one banana at a time, and only as a special treat when someone was sick.

Ultimately, Zhang says that other than not being able to visit her mother in China for Chinese New Year before she passed away, she has very few regrets regarding her decision to come to the U.S. Although she sometimes wonders about the alternate life she could’ve had in China, she says coming to the U.S. allowed her to both experience a new world and give her two daughters the opportunity to grow up in a more stable country.

“I just could not have any expectations,” Zhang said. “I think [the new] generation is much luckier than my generation. Back then, there was no, ‘Oh, I want to be a journalist or a lawyer or a doctor or whatever.’ Now, [my daughters] are here, and they received a good education, and they have those options.”

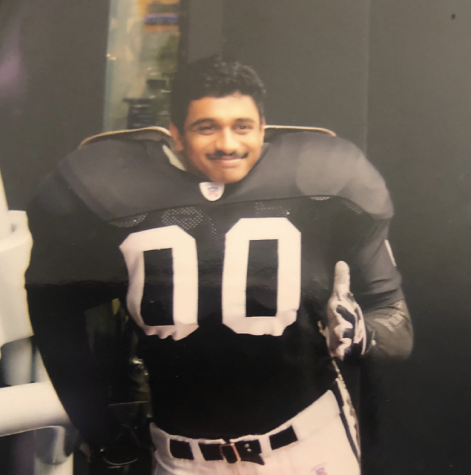

Manoj Jayadevan

The most distinctive thing that MVHS parent Manoj Jayadevan can recall from his first day in the United States is the speed of the taxi that picked him up. It was going 70 miles per hour — faster than the cars in India could go, because the taxis in the U.S. didn’t have to navigate the same crowded streets as those in India.

Jayadevan decided to immigrate from India to the U.S. in 2001 in pursuit of better job opportunities. He was interested in electrical engineering and wanted to begin working with nuclear reactors, which he couldn’t do at his current job — choosing to move to the U.S. was simply a matter of expanding his career options.

After landing in San Francisco (alone, because his family was planning to join him three months later) in anticipation of his new job in Sunnyvale, Jayadevan had to find a way to make 300 dollars last for two weeks, which was when he would receive his first paycheck.

Jayadevan remembers finding it initially difficult to adapt to the U.S. He didn’t know what he was experiencing when he found himself extremely sleepy in the days after the flight, because he had never heard of jet lag before. He ate chicken nuggets every day for the first six weeks — not only because they were inexpensive, but also because of the convenience of being able to simply order a “Number Six” at McDonald’s. He didn’t get a haircut for the first few months, because having slightly ove

rgrown hair was preferable to not having enough money to buy food. And, he remembers experiencing miniature culture shocks, like learning that unlike in India, in the U.S., people left a lot of room between each other when standing in lines — a lesson he learned after being told that he was “breathing down somebody’s neck” the first time he went to the bank.

Overall, Jayadevan believes that immigrating was “probably the best decision he ever made.” Although he misses the liveliness and connectedness of the people in India — the quiet suburb of Cupertino just doesn’t have the same festivals, dancing and ease of connecting with family and friends nearby — he finds moving to the U.S. allowed him to get out of his comfort zone and embrace new perspectives.

“I wouldn’t change anything,” Jayadevan said. “I think what happened to me in my younger years shaped me to where I am now. If I were to just stay back in India, my viewpoint of the world would have been very limited. [Immigrating] opened my eyes massively. Coming to America, I started meeting people from all parts of the world. It’s very diverse. It shapes your thinking — you take good things from all cultures.”

Tiffany Daugherty

It was late at night when MVHS parent Tiffany Daugherty’s flight landed in America, ending her long journey to the United States. Daugherty describes her childhood growing up in Vietnam as happy and carefree, living among a tight knit community. However, Daugherty’s happy childhood took a turn during the Vietnam War, when her family of 10 faced imminent danger. Because her father was a colonel in the South Vietnam military, there were times when the military of the North invaded, targeting families of high rank.

The immigration process for Daugherty’s family was relatively easy, as they were children of the war. After being sponsored by a family member in San Jose, Daugherty and her eight siblings were able to attend school. Before arriving in the U.S., Daugherty pictured America as a country filled with white picket fences, green grass and a friendly community. To her dismay, not only was there no green grass and white picket fences, but she also faced bullying and discrimination, where other kids made fun of her for being placed in ESL classes.

Due to her identity, Daugherty didn’t fully feel accepted as an American until college. To her, the college experience was different because of the lack of bullying and cliques. Because there wasn’t a select group of friends that she had to hang out with every single day, she felt that she was able to grow more independent and resilient.

“I think if anything, [immigrating here] made me stronger,” Daugherty said. “If I didn’t have to go through the bullying, I probably wouldn’t be where I’m at, because that taught me to stand up for myself. What happened when I was growing up here, it just got me to the point where I will not let people [walk over me].”

Now, Daugherty has lived in the Bay Area for almost 47 years. She says the Vietnamese community offers a feeling of belonging where her family is part of the culture, and would not think of moving anywhere else. Despite all the hardships she faced in the U.S., Daugherty says that she is most proud of her family.

“The most successful moment is when I [had] my children,” Daugherty said. “Everything else is secondary because they’re my life. I feel that’s like above everything. I think what happened to me in my younger years shaped me up to where I’m at right now. I’m very content where I’m at — I have a good job, good family, good morals [and] a lot of good great friends. I appreciate everything that I have, and I think if I didn’t have that when I was younger, I wouldn’t appreciate a lot of the things that I would now.”