True Beauty

Idolizing Eurocentric beauty standards prevents diverse representation

A narrow focus on Eurocentric beauty excludes much of the wider world.

October 7, 2022

In July of 2020, a skin-lightening product marketed mainly to the South Asian market called Fair and Lovely was renamed Glow and Lovely following marketing campaigns that emphasized lighter skin as a more attractive feature than darker skin. The change in the name was a result of backlash on how the brand profited off of Eurocentric beauty standards. However, despite this continued practice, 300 million people still use Glow and Lovely products each year.

Basing depictions of beauty around Eurocentric features aren’t confined by India’s borders — an unhealthy idolization of Eurocentric features is also deeply rooted in other Asian cultures. Eurocentric beauty standards have long been ingrained in societies around the world, with traits like fair skin, straight hair and large eyes being equated to being conventionally attractive.

In 2017, an estimated 1.3 million people worldwide underwent double eyelid surgery, according to the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. Commonly known as “Asian blepharoplasty,” double eyelid surgery is the most common cosmetic procedure requested in Asia and the third most common procedure requested by Asian Americans. Excess fat and skin are trimmed from the eyelid until a crease is formed, creating that “coveted double eyelid”. The risks include infection and bleeding, noticeable scarring, skin discoloration or, in rare cases, loss of eyesight.

Indeed, beauty is pain.

This immense pressure to fit into the Eurocentric norm is also exacerbated in pop culture. K-pop groups often have visuals, member(s) in the group who best fit the eurocentric-influenced Korean beauty standards. This “visual” label not only objectifies them as “beauty symbols,” but leaves an unhealthy impression on fans of what is considered “conventionally” beautiful. Unfortunately, this isn’t only limited to K-pop. Even comics, including True Beauty, bring light to the “classic” beauty, where the protagonist’s identity is surrounded by her makeup which emphasizes Eurocentric beauty standards. Beauty pageants and lists such as “TC Chandler’s most beautiful faces” further emphasize that beauty is influenced by objective standards that a few people are “blessed” with. Even science is used against us, as individuals like Bella Hadid, Ariana Grande and Taylor Swift are labeled “most beautiful people based on the golden ratio.”

It seems that in almost every country, every culture, every tradition, this narrow focus on Eurocentric beauty excludes much of the wider world, preventing representation of people of color in the media.

Having the social aesthetics of one race act as the beauty standard for the world influences young people of color, forcing them to compare themselves to those standards and put down their own ethnic features. This idolization of Eurocentric features that never belonged to people of color, which we try to claim anyways, further perpetuates the popularity of Eurocentric beauty in our communities. It not only creates a sense of longing for “superior” features, but plagues us with feelings of never being pretty or good enough. Essentially, it strips us of our own racial features and our identities.

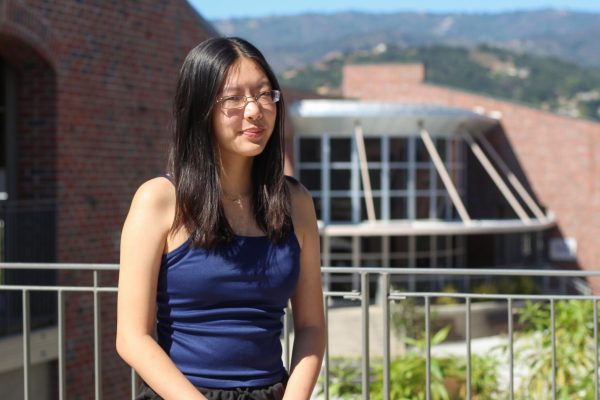

Students at MVHS may be especially susceptible to falling under the influence of such beauty standards. Given its large Asian population, students may feel more self-conscious because of the standards they are exposed to. From the culture in the community to influence from media, the influence of Eurocentric beauty has already seeped into our lives.

It’s hard to unlearn idolizing Eurocentrism given those before us have failed to do so. And it’s inevitable that no matter how hard we try to unlearn them, beauty standards that have become the dominant definition of beauty will still find their way into the insecurities of the next generation. But only by de-emphasizing the significance that Eurocentric beauty standards currently have in our lives, by embracing and representing features from all races and ethnicities, can we actively fight this social standard that caters to only one heritage.

On Oct. 1, a ban was set in Nigeria where foreign individuals were exempted as models and voiceover artists in advertisements. This ban was established to emphasize the hidden homegrown talent, beauty and diversity that stand within the nation’s borders. While it is unlikely to expect more bans in countries worldwide, taking small steps in our daily lives can contribute to getting rid of this narrative of “white beauty.”

We can start by diversifying our “for you page” by supporting influencers from different backgrounds of all types of skin colors, hair types and sizes. Especially in a world where our lives revolve around social media, a single message can make a huge impact. That message starts with us. We can start by highlighting our world’s inherent and diverse beauty through social media. We can start by spreading these ideas to our friends and family, then to their friends and family, and eventually to the entire world.

We can start by embracing universal beauty.