Limiting food waste at MVHS

An explanation of contributing factors and ways to combat excess leftovers

When schools opened in August of 2021, California’s free lunch program increased the number of students who ordered school lunch, raising concerns about the impact of food waste on the environment.

May 13, 2022

When schools opened in August of 2021, California’s statewide free lunch program guaranteed lunch to more than six million students at public schools. At MVHS, this increased the number of students who ordered school lunch, raising concerns about the impact of food waste on the environment as food waste makes up 30-40% of the nation’s food supply.

AP Environmental Science teacher Kyle Jones explains that food waste’s harm on the environment is generally indirect. When individuals dispose of their food, the rotting leftovers release methane gas into the atmosphere, which has an impact 25 times greater than carbon dioxide and makes up 10% of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

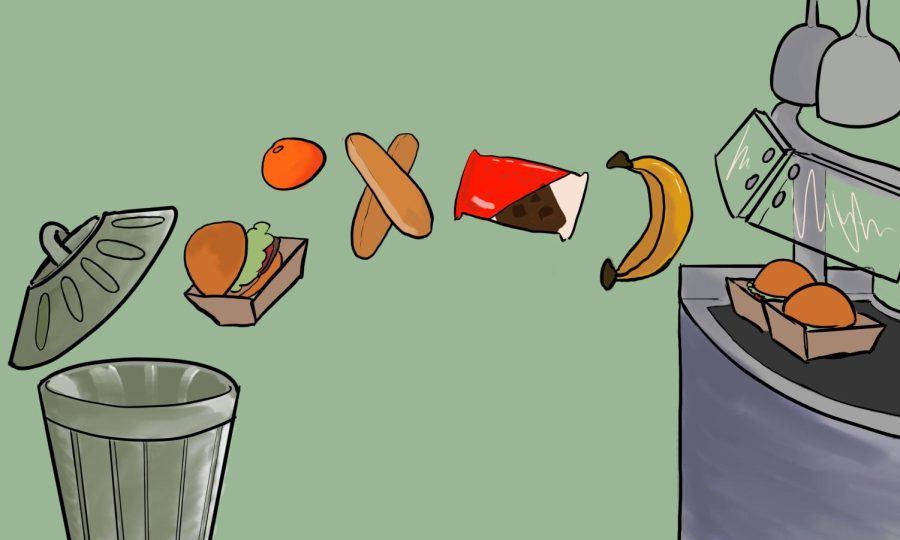

Food Services Manager Edgar Rodriguez says that the main source of food waste on campus is when students do not finish their meals and end up throwing it in the garbage.

“I don’t think [food waste] is a priority [for students],” Rodriguez said. “It doesn’t necessarily fall on their day-to-day things to do, and students are focused on classes and whatever it is that they need to focus on. Administration and myself, who is the manager here, should be the one focused on food waste.”

In MVHS’s cafeteria, junior and student worker Kevin Gong explains that it is difficult to estimate how much food the workers should prepare due to the “fluctuating” number of students who order lunch. However, since the cafeteria staff donates the extra food to a volunteer organization, Peninsula Food Runners, Rodriguez says that the kitchen’s food waste is “very minimal” with an average of 20 uneaten meals per day.

In addition to donating extra food, Rodriguez mentions the share table located outside the cafeteria where students can place the food they don’t want so that another student can pick it up. He also believes that offering friends uneaten food can help reduce waste on campus.

Jones shares that another way the school can mitigate the impact of food waste is by providing a compost bin, in which its contents can be transferred to the school’s garden or nearby composting facilities. However, he recognizes that this solution would result in “investing a little more resources at the school level, and that just means more staff, more money.”

Implementing compost bins would result in the custodial staff having to undertake extra labor to sort out the contents, which requires both more manpower and money. This system would also place responsibility on students to actually use compost bins correctly, taking time to sort their trash into different containers. Jones is skeptical that this type of plan would work, saying that most students “just throw stuff wherever it’s the closest.”

Jones also emphasizes the importance for teachers to educate students of proper ways to dispose of their food waste.

“I think food waste in general is overlooked by most developed countries in affluent communities, because food to an affluent community is not really a limiting factor,” Jones said. “We have so much food at our disposal that throwing food away, so we don’t really look at it because it doesn’t really bother us [or] affect us directly.”

Jones believes that the easiest way to solve food waste is if people were to only select the food items they need.

“When I think of food waste, I think the environmental piece is important, but I also think the idea of food waste is kind of a privilege to an extent,” Jones said. “From a social or ethical kind of framework, wasting food is something that people should be more aware of because there are people who don’t get the kind of nutrition that we can afford in our community. It’s more impactful for me to think of it less from an environmental perspective and more from a privilege and like, ‘What is my responsibility knowing that there are people in the world who would really be able to benefit from the thing that I’m just throwing in the trash.’”