Can we use the N-word? No.

Examining the recent district proposal to prohibit the use of the N-word by non-Black students in literature and history contexts

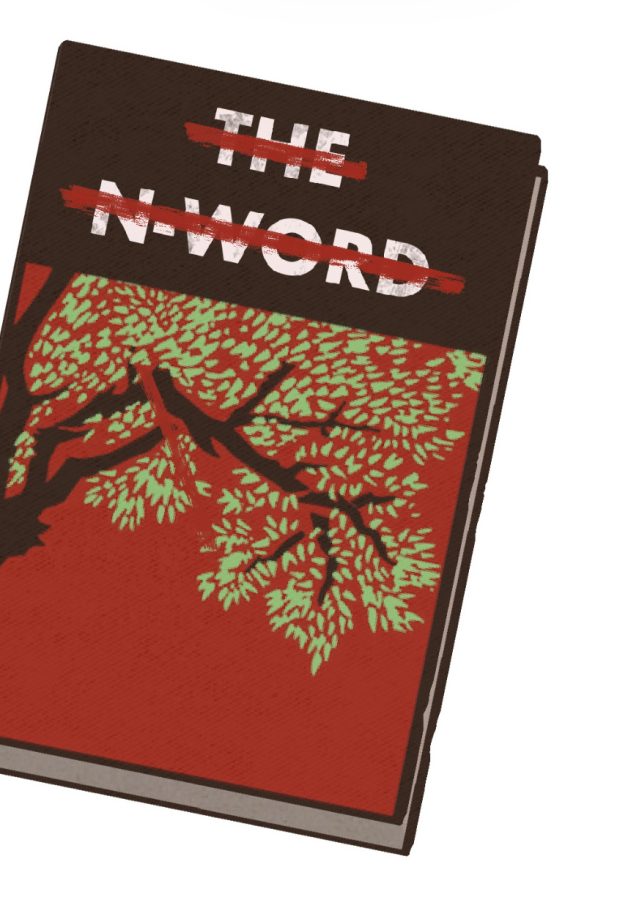

Books like “To Kill a Mockingbird” are read in literature classrooms feature the N-word.

March 18, 2022

In a recent district-wide proposal developed by Cupertino High School teacher Elise Robinson, teachers across English and Social Studies departments at all five FUHSD sites are urged to prohibit the use of the N-word under any circumstance by non-Black students, including in educational contexts where the slur might be mentioned in texts in the curriculum. The proposal states that several anti-racist texts should be employed as resources to educate the community on the word’s specific history, and that the slur is both a “chief symbol of white racism” and “a term of exclusion, a verbal justification for discrimination.”

Although many Literature and History teachers had previously prohibited the use of the N-word in the classroom, Robinson wants to standardize this norm across all humanities classes. Robinson passed along her suggestion to Robert Javier, the Fremont Education Association VP Equity Chair and Fremont High School English teacher, who then reached out to Greg Merrick, the FUHSD English curriculum lead and CHS teacher and Social Science curriculum lead Vivianna Torres. The proposal was created in January and outlines that the N-word should not be spoken aloud or written in any educational setting.

“The whole point of sharing this [proposal] with the Curriculum Leads is to broaden the scope of this conversation, especially to educate teachers to be effective, appropriate, professional, sensitive and mindful in their content delivery,” Javier said. “I have not witnessed any teachers expressing the N-word, but anecdotes from staff at different sites and from students clearly show that there are teachers who are not educated or aware that this is something we do need to systematically address. If we as teachers model this correctly for students, we can only hope we have helped students think twice about its casual usage.”

Through his experience teaching at CHS for 24 years, Merrick expresses that he has seen the N-word used in books such as “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” “Their Eyes Were Watching God,” “The Invisible Man” and “To Kill a Mockingbird.” However, he believes that the flippant use of the N-word isn’t only linked to its presence in literature texts.

“We know [the N-word is] in the media that many of our students and, to be honest, the adults on campuses consume,” Merrick said. “Whether that might be in the form of music, TV or movies, [our] patterns of media consumption probably contribute to this phenomenon to some degree. And that is part of the reason why we’re developing this norm around prohibiting the use of it in English and Social Studies classes.”

MVHS alumna ‘21 Molly Mobley describes a similar experience witnessing the use of the N-word by non-Black students on campus. Having experienced this on several accounts, Mobley stresses the “moral obligation” of teachers at MVHS to establish and enforce the prohibition of non-Black students using the N-word in their classrooms — she shares its importance in “mak[ing] sure that their students feel safe in their classrooms and equal to their peers.”

“I think that it’s normalized everywhere in America, unfortunately, which is why it’s also normalized here,” Mobley said. “There’s a lot of non-Black people who are upset that there’s something that Black people have that they don’t have. It’s this really kind of backwards logic of, ‘Why do they get some privilege?’”

Mobley says it is important that non-Black students are taught the history behind the N-word and its multiple forms. She states that if students don’t have proper historical context on all race issues, a lack of productive and meaningful conversations will inevitably cause society to repeat the past. Mobley encourages both teachers and students to pursue these topics independently through research rather than relying on other students in the Black community. With hopes of fulfilling this, the English department leads at FUHSD have done research in order to provide students and teachers with the proper insightful resources.

We found an article written by someone who identifies as Asian American and talked a little bit about how, from an Asian American perspective, it’s important to be mindful of not using the word and how it intersects with some of the interest[s] of the Asian American community,” Merrick said. “We grabbed resources like that, designed to be accessible to students so that they can understand them and hear them from a variety of perspectives.”

According to Javier, while it is crucial to establish norms for other offensive terms, it is also essential to recognize the significance of the N-word and its personal impact on many staff and students.

“It is important that we do not lump in the N-word with all offensive terms [and] racial slurs because the N-word is a very specific, systemic thing that has roots and history that continue to feed the anti-black sentiments that run rampant in society and unfortunately in our schools,” Javier said. “But it clearly falls in line with a zero-tolerance for such hate speech.”

Merrick hopes that the future of literature and history curricula maintain diversity by presenting a myriad set of narratives to students.

“I hope that we continue to move towards literature that allows all of our students with their diverse identities to see themselves fairly and humanly or humanely represented in literature,” Merrick said. “[We hope to do this in] ways that are respectful, that celebrates their cultural identities, their racial, ethnic identities, their gender identities, all those sorts of things.”