Eat bitter(sweet)

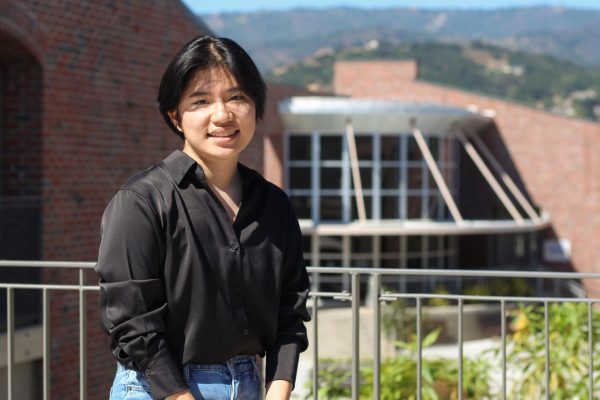

Learning how to 吃苦, or “eat bitter”

Learning to “eat bitter” forced me to confront the pessimistic mindset I’d built around hard work and success.

Around the winter of fourth grade, I got a cold. This wasn’t anything out of the ordinary; in fact, it was pretty much guaranteed that I’d get at least a small cough every year when winter rolled around. Yet, I still went to my parents complaining of a sore throat, hoping that perhaps I could get out of doing some homework, to which they reasoned that I did not need my throat to do math, and dismissed me.

After that, I spent the whole day trying to subtly hint at my parents that my coughing was killing me and I’d die without interference. They noticed, of course, because an angry 9-year-old is about as subtle as a bull in a china shop, but instead of letting me kick back and relax, my parents pulled out a jar of herbal cough medicine. It was a thick molasses-esque cough syrup that coated your tongue with a cloying, choking sweetness and yet was also unbelievably bitter at the same time. It was also, in my 9-year-old eyes, either the reincarnation of Satan himself or literal devil spawn and I didn’t trust either, so I stayed the heck away from it until it was inevitably forced down my throat.

Already tired and grumpy from lack of sleep, the giant spoonful of medicine that my mom doled out to me was the straw that broke the camel’s back and the next thing I knew I was bawling on the floor. My parents were also (understandably) tired and grumpy from listening to me pretend to cough my lungs out every time they walked past, so they snapped that I needed to learn how to 吃苦, or “eat bitter” — a phrase that’d soon become intertwined in every aspect of my life.

“Eat bitter” is a Chinese proverb that means to endure hardships or persevere despite difficulty, and it was a phrase that I despised for the longest time. When I was younger, it seemed like my parents were constantly pushing the narrative that I needed to experience pain to do well.

No pain, no gain. What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.

Every time my achievements weren’t up to par with my parents’ expectations, they’d tell me I hadn’t truly learned how to “eat bitter.” As a 9-year-old, I didn’t understand why I needed to seek out pain to be perceived as hardworking or to achieve what I needed to do. In fact, there were times when even when I did well on tests, my parents would still tell me that I hadn’t truly learned how to “eat bitter.”

I looked at math problems my parents made me do, the mistakes I made on those tests as an obstacle — an iron wall that stood impenetrable and unconquerable no matter how hard I pushed. Eventually, I started giving less effort each time I encountered one; what was the point of expending time and energy on trying to break a wall that remained unyielding despite my best efforts? I avoided having to study or work, and when I was forced to, I approached it with the mentality of a battle-weary soldier.

To me, it was almost ironic in a way. “Eat bitter” really was such an apt description, because hard work was just like eating a spoonful of that bitter herbal medicine — nauseating and hard to swallow, with a bitterness that lingered far longer than I thought it could.

However, as I grew older, I realized that I was looking at things the wrong way.

My problem was never with my results or my scores, but rather my mindset. I’ve always dreaded working hard because I was so caught up in everything I couldn’t do rather than what I could. I did the bare minimum to scrape by without putting in any more effort than I needed. With an attitude like that, it was no wonder my test scores would take the occasional nosedive into the deep end. The good scores were always met with annoyance from my parents because they knew that I hadn’t worked for it, but rather relied on my own natural smarts and luck. My parents weren’t upset with the results, but that I was giving up before I even started, that I was limiting myself from reaching my full potential. The iron wall shouldn’t have been an obstacle, but rather an opportunity for me to hone my skills further.

The truth is, nothing that you want can be achieved without hard work, without giving something in return. Eating bitter doesn’t mean to hurt yourself in search of something you can never reach. It’s inevitable that life will bring hardships your way. You don’t go looking for pain because pain will naturally find you. What “eat bitter” promotes is that you should approach this pain as a chance to learn and grow rather than something that’s impossible to overcome.

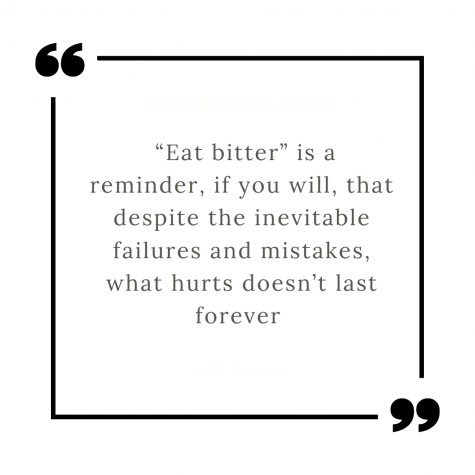

Despite its seemingly negative connotation, “eat bitter” is a reminder, if you will, that despite the inevitable failures and mistakes, what hurts doesn’t last forever — and that after you overcome it, there’s something sweeter waiting for you on the other side.

And after it all, I can confidently say that I’ve finally learned how to eat bitter(sweet).