Sexual harassment procedures at FUHSD and Bay Area high schools

Examining rape culture and sexual harassment policies, including Title IX, at FUHSD and Bay Area high schools

June 3, 2021

Under the leadership of former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, Title IX — an expansive piece of federal legislation established in 1972 that prohibits sex-based discrimination in educational institutions — was modified in May of 2020 in regards to implications for alleged perpetrators in sexual assault cases. DeVos and critics claimed that part of the prior legislation “pushed schools to find students guilty,” although victims’ rights advocate groups claimed it had provided “long overdue protections for sexual assault survivors,” according to a Washington Post article.

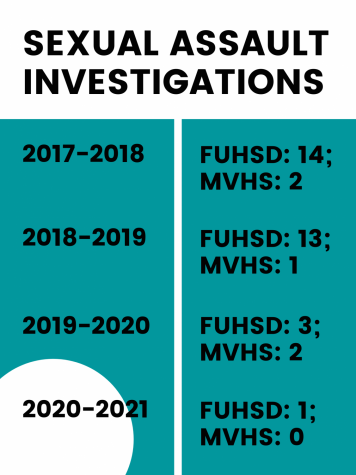

Trudy Gross, an associate superintendent of FUHSD and an FUHSD Title IX coordinator, explains that the district updated its Title IX, Sexual Harassment and Uniform Complaint Procedure prior to the 2017-2018 school year. Since then, FUHSD has also been keeping records of sexual assault cases in the district; in the 2020-21 school year, there has been one investigation in the district, and none at MVHS.

Gross explains that during investigations, the FUHSD policies look at whether the incidents were pervasive, which refers to incidents occurring across a school environment or institution; persistent, which refers to the frequency of the incidents; or severe, which refers to sexual assault or rape.

“This year, the updated legislation has narrowed what we can consider Title IX,” Gross said. “Now for us as a district, we would still follow our sexual harassment policies and determine, in investigations, if that policy was broken. The administrators and I would consult and we would decide whether or not it is persistent and pervasive enough to say our sexual harassment policy in the district was violated and we would still investigate and have an outcome to that. Although the legislation got narrower, we can still investigate everything we were previously investigating. It just falls a little differently in terms of what we’re calling it.”

The Title IX legislation includes a component about sports, which, according to MVHS Athletics Director Nick Bonacorsi, “is intended to ensure fairness and equity across the different genders,” and also includes creating safe environments for all athletes and ensuring that everyone has an equal voice, regardless of gender.

Bonacorsi explains that while athletic participation is not looked at significantly, the Title IX amendment is emphasized most often in terms of funding and facilities. For instance, the boys baseball team and the girls softball team must have equal opportunities.

“We’re thoughtful about it on the front end,” Bonacorsi said. “So it’s about being more preventative than reactionary. If we give something to one sport we try and think about, on the back end, what we need to give to the other to keep things balanced. And for us, specifically, our biggest thing is the ability to pay coaches. And that’s probably where we look at it the most, in trying to balance how we can allot stipends for coaching to keep it balanced across the different genders in sports.”

Growing up, MVHS English teacher Kate Evard attended Los Altos High School and has lived in the Bay Area since. Title IX legislation was passed as a part of education amendments in 1972 and was therefore already in place when Evard graduated in ‘81.

However, she remembers the problem of rape culture and sexual assault being pervasive during her time in high school and says that, although there has been more dialogue about it since, she believes the culture has “not changed nearly enough.”

“I do know a lot of girls that are women now, my age and older, that were assaulted in high school and never told anyone,” Evard said. “Didn’t tell their parents, maybe told their best friend, but they never told anyone else. Because of the shame and so forth, because we all know that that’s still a big thing. That’s huge. Most victims do not ever come forward for that reason. But I think there is more dialogue about it than there used to be. I don’t remember it ever even being a point of discussion around my school, in the news, in the media.”

Evard explains that some of the causes of rape culture stem from the ideas of entitlement and privilege; for instance, she says there is a particular tendency for male high school sports teams to participate in these types of actions, citing the example of the alleged sexual assault cases at Los Gatos High School. She says that it is “unfortunately a part of our culture that women are blamed for their own assaults,” and condemns rhetoric like “boys will be boys.”

“[The phrase boys will be boys] is like, ‘Let’s teach the girls how to not be raped,’” Evard said. “Well, let’s teach the boys to not rape. Let’s do that first. It’s ridiculous. I don’t think the message comes across strong enough … and I know a lot of parents with nice young men and I know that our coaches at MVHS are exceptional. So it’s not them. But for some reason there’s such a thing in [some boys’] minds as non-consensual sex. That is rape. There’s no such thing as non-consensual sex. You either consent, or you don’t. No consent means rape. No means no.”

Bonacorsi explains that during his time as athletic director — five years — there have not been incidents of Title IX violations within the MVHS athletic program or among athletes.

He explains that there has, however, been discourse about the problems of bullying and hazing in sports, and his approach to that has been to focus on student athlete leadership and training. The MVHS athletics department has partnered with a program called the Positive Coaching Alliance (PCA), which runs workshops for coaches, as well as team captains.

“Our approach has been more about trying to engage our student leaders and give them tools and training to utilize those skills, and then to give them a voice at the same time,” Bonacorsi said. “And so our thought was, if we can empower captains, they can help be leaders of change on their teams and within their programs. From our perspective, it was more about the small scale, hazing, bullying stuff, that would happen traditionally in sports. For example, when I played sports [on] my football team, it was common that the freshmen had to clean up the gear, and put out the gear everyday, or there were roles that were specifically for freshmen only, and those are by definition elements of hazing, so we wanted to try and address those kind of things.”

Bonacorsi hopes that by taking these initiatives, athletes learn to take responsibility for their actions. He notes that cases of sexual harassment or rape traditionally take place when coaches or athletic directors aren’t around, and this was his way of ensuring that MVHS had a program in place where “athletes felt comfortable either talking to captains or talking to their team leaders and having a way to get that information up the chain,” and hopes that they are moving towards establishing that type of healthy culture.

Gross adds that, in her experience, most of the sexual harassment investigations she’s encountered in the FUHSD community have pertained to problems in relationships. She explains that in a healthy relationship, communication, and therefore active consent, go hand-in-hand.

“[What matters is] not what a person is doing, it’s what a person is saying,” Gross said. “I think those are challenges for humans, but when people are younger, it’s harder; you’re just learning to communicate and to say things that might seem uncomfortable or scary or weird or whatever it might be. And then there’s also just being impulsive, like ‘Oh this is fun, this feels good,’ whatever it might be. That impulsivity might override better judgment at certain periods of time, and some of that is about growing up.”

According to Gross, previously, most students learned about topics like consent and healthy relationships during sex education in freshman Biology, as well as at the beginning of the school year when administrators talked about school regulations and expectations. The school administration has taken additional actions this year such as having students learn about issues including sexual harassment through modules and presentations during Advisory.

Gross believes that such actions have been received with substantial interest and engagement by students and points to the SAFER Choices virtual assemblies hosted by the Center for Respect as an example. Gross notes that there has been “excellent participation” at the assemblies across FUHSD schools, despite them being optional and held on an asynchronous Wednesdays, indicating that “it is something that students know they want to hear about, that they want others to be talking about [and] that they want others to hear about.”

“Whether it’s through Advisory or assemblies, I think we want to find a way where there’s some specific education each year around sexual harassment, appropriate interactions, behavior [and] follow up,” Gross said. “It’s just important for us to, after we’ve finished this year’s round of virtual assemblies [and] received good feedback from students, debrief and say, ‘OK, what’s the best way to keep doing this in the future.’”

Gross emphasizes the importance of implementing feedback, as she herself has done after having individual conversations with students who shared their perspectives with her. For instance, after speaking with several students, she added a FAQ section on Title IX to the district website and later updated the Title IX information to be more accessible on the MVHS website as well.

Similarly, Bonacorsi says he hopes to have conversations about sexual assault and rape culture with his athletes, as well as provide actionable steps — he explains that the way he set up the leadership model in the athletic program lends itself to doing so. Each sports team has captains that hold leadership positions during their respective seasons, but there is also a much smaller group called the Student Athletic Senate, who act as leaders throughout the school year.

“If this wasn’t COVID and we were together and we were actually meeting, we could bring those type of topics [like sexual assault] to that group, because I think it’s more meaningful and more important when it becomes student athlete-driven [rather] than something coming from me, or from Mr. [Mike] White or from Mr. [Ben] Clausnitzer,” Bonacorsi said. “I think something that we can do is put that power a little bit more into the Senate’s hands, and let them come up with ways to differentiate and make it different from what the school is doing, and try and target athletes more specifically.”

In past years, Evard would regularly discuss the topic of sexual assault with her class when the opportunity arose. She didn’t plan the discussions or a specific lesson, but notes that they tended to come up during more gender-oriented units, such as while reading “Their Eyes Were Watching God.” Although she hasn’t had such discussions this year because of the lack of trust and safety in a remote classroom, she still emphasizes the importance of talking about the problem, because “it’s everywhere — that’s the thing: there’s no school or district where it’s not a thing. It’s incredibly pervasive.”

Gross emphasizes that regardless of when a victim comes forward — even if it’s much after the incident, as is often the case — it is important for her to offer support.

“No matter what, no matter when [victims] decide to tell their story, it is important to tell that story and then for us to respond to it to investigate as appropriate and follow up,” Gross said. “I’ve had a number of students reach out to me over the last year and this year, so maybe as it has become more prominent — they’re hearing us talk about it more and then they are talking to us about it more.”