‘Attack on Titan’ earns its place as a classic manga

Author Hajime Isayama’s epic war thriller sets the bar high for Japanese comics of the future

“Attack on Titan” has consistently reinvented itself with every new chapter, and now that the 139th and final chapter of the manga has been released, the series has cemented itself as a classic. Photo courtesy of Kodansha Comics

April 25, 2021

Mild spoilers for “Attack on Titan” below.

Written and drawn by author Hajime Isayama, “Attack on Titan” is one of the most popular anime and manga series of the 2010s. Since it began over 12 years ago, the series has continuously gained more recognition in the mainstream community — the manga has sold over 100 million copies and is ranked as one of the bestselling Japanese comic series of all time. “Attack on Titan” has consistently reinvented itself with every new chapter, and now that the 139th and final chapter of the manga has been released, the series has cemented itself as a classic.

“Attack on Titan” set up its first chapter with a simple premise: the last remnants of humanity are trapped within three concentric walls that have been preventing large, grotesque humanoid creatures called “titans” — man-eating behemoths that are as terrifying as they are mindless — from entering and destroying the human race.

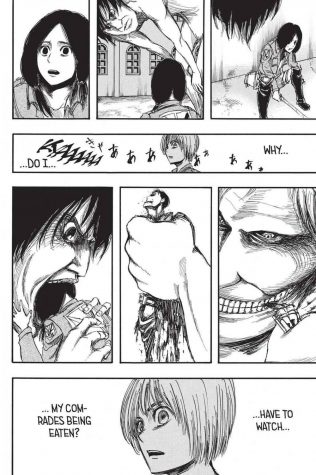

The first chapter starts off with (quite literally) a bang, when a titan, taller than the walls themselves, appears at the front of one of the outermost cities, Shiganshina, and breaks open the gates to let smaller titans enter the city. This is where main characters and lifelong friends Eren Yeager, Mikasa Ackerman and Armin Arlert live. After helplessly watching his mother be eaten by a titan, Eren vows to fight back against them and joins the military along with his two companions, where he meets a variety of personalities, each with their own unique experiences. However, as the story progresses, the plot develops into something completely unlike the post- apocalyptic drama hinted at in the premise in its nine vastly different story arcs, each with their own thematic feel.

One immediate positive aspect of its storyline is how uncompromising and unforgiving it is in following the rules that it sets up, one example being the battle scenes with titans. The military uses omni-dimensional gear to fight titans, waist attachments which allow them to grapple onto buildings, trees and even the beings themselves. However, if characters have nothing to grapple onto, or grapple into the reach of the titans, they get eaten. This gear also runs on gas, and if soldiers run out of it, they most likely get eaten as well. This rule also applies to every character in the series, with even some main characters getting killed in this way.

The jarring action of the manga is also underlined through its brutal depiction of these fatal mistakes, with many panels dedicated to showing limbs being eaten, dismembered body parts and gruesome deaths of beloved characters. Some moments feel truly hopeless, as it seems that the only way for soldiers to win a battle is through crippling sacrifices, a common conversation point for many of the characters in the story. Earlier chapters do this so often that many battles can feel claustrophobic as the characters gain very few victories compared to the price of life they have to exchange them with.

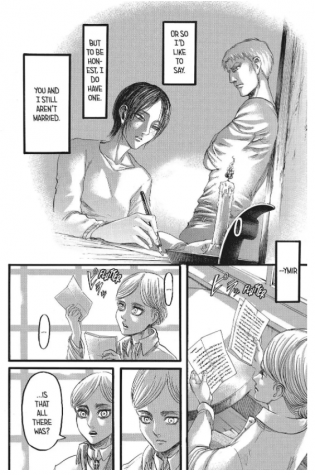

Not only known for its violence, “Attack on Titan” takes considerable amounts of time to work through making its characters likable and interesting. While character development takes a backseat in the opening three arcs of the series, later arcs focus solely on making them more complex, by adding well written dialogue that seeks to expand upon the relationships between them. Additionally, the representation of various social groups in the story is maturely handled, never being the focal point of their character. For example, the lesbian relationship between characters Christa and Ymir is a breath of fresh air, with entire chapters dedicated to fleshing out their backstory as well as their tragic companionship, delving deep into their backstories as well as how they connect back to the overarching plot.

By the end of the manga’s nine arcs, the story evolves into something almost unrecognizable as it builds on itself and slowly peels away layers of many different mysteries behind the world and its characters.

It should be noted that the story shifts so much to the point that it constantly changes genres, and this is especially clear in the “Uprising” arc, which is the midpoint of the series. The story changes the main conflict towards its own royal government, going in depth into the oppressive monarchy and the weak and greedy nature of its officials. The cast of characters are suddenly pitted against humans instead of titans and constantly question whether killing them is truly best for the human race. The story goes from focusing on warfare to tackling espionage, scheming and suspense, with the end goal of overthrowing the corrupt monarchy and solving the internal oppression towards the citizenry. Instead of heavy titan violence, this part of the series is more nuanced and contains many moving parts, all converging towards a satisfying climax, where the government is overthrown and a new story arc has immediately begun.

However, the series is not without its flaws. Besides the overall pacing of the story, the art is considerably weak and amateurish, especially in the beginning chapters of the series. Being Isayama’s first-ever published manga, it can be expected that some parts of his artwork are not fully realized or well-developed, but many of these earlier chapters contain art that can be perceived as inexperienced and even lazy.

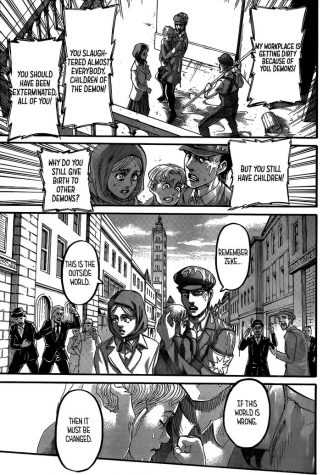

The series has also been met with criticism in terms of its portrayal of fascist and ultra-nationalist government systems, as well as questionable design choices that can also be interpreted as anti-semitic. During the “Marley” arc of the series, the world of “Attack on Titan” expands beyond its walls to reveal the existence of Marley, a military-run nation that powers its economy on the use of titans in warfare to achieve its goals. The arc also examines racial discrimination that has created horrible conditions for both sides of the conflict. The top leaders of the nation are all part of the military and have ingrained racist propaganda against the people in the walls in order to wage war and gain further economic control over the world. The people in the walls, called Eldians, are spread around the world and are openly discriminated against due to past injustices committed by their forefathers. In Marley, Eldians are segregated and forced to live in ghettos, recognizable by the distinct armbands that they have to wear, which is clearly reminiscent of how Jewish people were discriminated against in the Third Reich. While the connection as a focal part of this arc is most likely not Isayama’s intention, the way it is presented can definitely be interpreted as out of touch.

Overall, the imagination and unique world that the story builds up within its thousands of panels is well worth the adventure. The storyline improves with each chapter, each building on the last one and supplementing it with complex characters, methodical worldbuilding and invigorating thematic elements. It treats its readers with respect, withholding important bits of information and instead leaving small bread crumbs of plot points that eventually culminate into satisfying plot reveals. The constant evolution of “Attack on Titan” and the finished product of its 12 year journey easily sets it up as a go-to classic and sets the bar for all future manga works to come.