Closing off the semester

What Closing Week means and where it came from

Junior Devin Gupta highlights an AP US History DBQ || Photo by Devin Gupta

Teaching during a pandemic is difficult.

Teachers not only lack robust feedback from the visual cues they would get in a physical classroom, they also can’t practically assign traditional assignments or formal assessments. These differences are why FUHSD decided to implement Closing Week, a replacement of traditional Finals Week.

For Closing Week, teachers have been encouraged by FUHSD administration to arrange low-risk final exams or projects — testing that doesn’t negatively impact students’ final grades — as a way of reducing stress for students and staff in a difficult online learning environment. According to Clausnitzer, the rebranding of Finals Week provides an opportunity for teachers to administer assessments differently.

“You could give a final exam, yes,” Clausnitzer said. “But what else could you do? You could give a unit exam rather than a comprehensive final exam. If you gave a final exam, it could be a no-harm final exam. You could have some sort of culminating activity. It could just be a normal class.”

While the administration hopes that teachers reshape their final exams to better accommodate for the challenges of distance learning, California Education Code 49066 designates teachers as the sole decision makers for their students’ grades and assignments in all cases except when teachers are charged with fraud, mistakes, bad faith or incompetence.

Yet for the past few years, U.S. History teacher Bonnie Belshe has noticed that teachers have already been talking about how to make final exams no-harm. But the uniqueness of the COVID-19 pandemic and the push from administration have expedited the process, bringing conversations about alternative final assessments like no-harm testing to the center of teacher discussions.

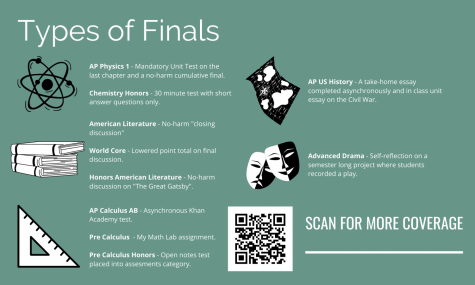

Before distance learning, Belshe used to host a cumulative set of AP exam style short answer questions on the Friday before finals week, in addition to a two-hour cumulative multiple choice test and document-based short essay (DBQ) on the day of finals. This year, Belshe is considering opting for only a take-home DBQ, a test students can work on in their own time, with the possibility of another memory-based short essay during the 90-minute closing period.

“The big difference between online and in-person [learning is that] we just can’t do the same amount of things online,” Belshe said. “So I’m trying to be very reflective of that and match that understanding with respect to the understanding that finals are always stressful. Then adding a pandemic, we’ve moved into the purple tier, people I know are concerned about their family … and so [I’m] just trying to make sure that I can have practices that [match] those concerns and mak[e] sure that both the emotional needs and academic needs are being met.”

Throughout the semester, junior Atmaja Patil noticed teachers giving many low-risk tests instead of “high-risk” tests. For Patil, one of the advantages of this system, in addition to having a “far less stressful” learning experience, is that internet issues or not ideal testing environments won’t negatively impact a student’s grade.

On the other hand, she is worried by the lack of consistency with teachers around Closing Week. The change in assessment style and varying degrees of compliance to the recommendations among teachers have created a very diverse set of testing methods, causing variability and uncertainty in expectations for students, even among students who are taking the same courses.

“There are some teachers, I’ve heard among sophomores, that have threatened to violate the no-harm policy, but haven’t announced what their final will be, so no one knows for sure,” Patil said. “If teachers leave that lingering threat, it’s another source of stress and that’s frustrating.”

As Closing Week approaches, teachers will begin to release class plans and grading policies for final assessments that try to accommodate students during distance learning. In the meantime, Clausnitzer wants to ensure that while teacher use accommodating testing methods, students don’t abuse the privilege they are being given and continue to work hard.

“I would hope teachers react [by] trying to think about the unique circumstances that we’re in … and providing students an opportunity [to have alternative finals],” Clausnitzer said. “For our students, if a teacher is doing something different, providing an opportunity, then yes, I want folks to enjoy that opportunity, but it also means put[ting] in a good faith effort … into doing the best that you can.”