The Rise and Fall of CUSDs Enrollment and Expenditures

Exploring CUSDs financial and enrollment situation throughout the years

November 26, 2020

The central question on CUSD board members’ minds going into the night of March 3, 2020 was: Would CUSD receive financial assistance for its current deficit spending? Parcel Tax Measure O would have provided CUSD an additional 4.3 million dollars a year. With a two thirds majority needed to pass, voters said no, defeating Measure O and forcing CUSD board members to make complicated choices including the possibility of closing some schools.

Photo from Lawson Middle School

Lawson Middle School during the summer.

Part 1: The heyday

Exploring CUSDs past financial wellbeing in the early 2000s

When Dr. William Bragg took over as CUSD superintendent in the late 1990s, CUSD was in a state he refers to as “growth mode,” in which the population of the district was growing at a rapid pace. Pearl Cheng, who was a board member at the time, saw Bragg as the perfect candidate to improve student learning, open a new middle school and transition CUSD junior high schools to middle schools.

“[The late 1990s and early 2000s] was a time when we definitely saw another upswing in population, and our demographic studies showed that those upswings were going to have us hit major capacity issues at the middle school level,” Bragg said. “One of our big actions at that time was to plan for and determine how to open a new middle school.”

Bragg was originally an elementary school teacher for 11 years. He first became the first principal of Pioneer Elementary School before becoming the Head of Personnel and then the Assistant Superintendent in Southern California. Bragg later became Deputy Superintendent of the Oceanside School District, and finally, accepted an offer from CUSD to become its new superintendent in 1990.

While creating his plan, Braggs reached out to the community to brainstorm ideas and figure out how to best redraw the districts.

“One of the issues we had was determining how we were going to redraw the districts for the middle schools,” Bragg said. “Everything involved a process; everybody had to be heard and everybody had an opinion on what was going to work and what was not going to work. We took a lot of time with the community [and] engaged in these conversations about what the fifth middle school would be like.”

Bragg notes that the board and community came up with “about 12 to 15 alternative plans,” but they ultimately settled on one that redrew the district by moving some students from the Kennedy Middle School zone to the new Lawson Middle School.

“We knew [that redrawing the district’s school zones] would take … a very intentional and strategic community outreach and community input process,” Cheng said. “My team and I, with Dr. Bragg, did a many-months process [with] community members, no different then what’s happening today, that helped assess the demographic study, the current state of boundaries and current populations to then determine a full range of options.”

Cheng notes that at the time of the planning of Lawson Middle School, some KMS parents were concerned about the academic standards at the new middle school.

“There was hesitation, trepidation and concern all throughout that process,” Cheng said. “To this day … we are [still] an amazing school district with quality and excellence everywhere you look. So, of course, [Lawson] today is excelling.”

During Bragg’s tenure, the district’s population was steeply increasing, which meant a subsequent increase in CUSD funds.

“Because we were such a populous school district … we didn’t have any problems getting kids to come to our schools,” Bragg said. “If you’re a growing district, you are financially much better off than if you’re declining. That’s because the increased revenue you receive through increased students, not all of that has to go to pay for the teachers and the cost of educating kids. A lot of that can go to [other projects such as] infrastructure.”

Bragg converted multiple junior high schools — schools with only seventh and eighth graders — to traditional middle schools with sixth, seventh and eighth grade levels.

“The board [at the time] felt the need to move to a true middle school concept,” Bragg said. “We felt that sixth graders would have a more engaging opportunity at a middle school where they are interacting with sixth, seventh and eighth graders.”

However, Bragg adds that he felt that his reform of CUSD’s teacher leadership was more influential than opening Lawson Middle School.

“One of the reasons we tried to build up leadership capacity is to have teachers take more ownership of how the schools run and responsibility for the effectiveness of what they were doing and working together, as opposed to having all [of the leadership] vested into one group of people,” Bragg said.

Chris Roels, a Murdock Portal Elementary School teacher present during Bragg’s tenure as superintendent, believes that this type of teacher-run leadership was effective and useful. He believes that through his years of teaching, teacher-led programs have become farther and fewer between. Roels believes that an increase in these programs would be highly beneficial for newer teachers who may apply these leadership skills to their teaching style in the future.

“I don’t think the experts [or lead teachers] are very visible today,” Roels said. “In terms of our organization as a district, as a veteran teacher, I don’t see a science newsletter or things of that sort … Just in general, I don’t think that if you went from teacher to teacher and said, ‘Who [are] the math lead teachers right now?’ or ‘Who are the science lead teachers?’ I don’t think that people would actually come up with any names.”

Despite the district having enough funding, Bragg states that CUSD is also funded by the state, which passes annual budgets. Therefore, he believes it is important for school districts to keep low costs just in case school districts — especially those reliant on state funds — funding is cut.

Bragg’s administration oversaw the majority of growth of CUSD in the last 30 years. With no predictions of declining enrollments in CUSD, the administration was in growth mode; CUSD would continue to grow until the 2000s. According to Cheng, CUSD and Foothill-DeAnza are now experiencing declining enrollment in contrast to the early 2000s, which had an impact on funding.

“The biggest issue schools always face is state funding and whether or not there’s going to be enough money and whether the state has the money they need to do,” Bragg said.

Bragg believes that his administration had no major shortcomings, and that the current deficit spending could not have been predicted by his administration since they were more focused on growth. However, Bragg does not see CUSD’s financial issues as new. According to him, around 30 years before his leadership, CUSD managed over 30 schools before reducing in size due to declining enrollment. His administration oversaw a significant growth due to the increasing relevance of Silicon Valley.

“You have to be cognizant of [what happens] once you turn that corner and start declining, which happens in every district; it happened before I got there in Cupertino,” Bragg said. “It was a huge district in the [1950s], I think they had an enrollment of over 25,000 students — they had probably 50 schools [and] they closed and sold off many of those [as enrollment declined].”

Cheng adds that the Cupertino Education Endowment Foundation (CEEF) 一 which provides funding from private donors to support educational purposes 一 was established due to Cupertino’s shrinking population in the early 1980s.

Bragg says that by the time his tenure at CUSD ended, much of the growth that had occurred in CUSD had plateaued in 2006.

“When I had left, we had done most of the growth that was going to happen,” Bragg said. “We had plenty of room to anticipate some [more] growth [in the future], so I don’t think the district was in a position to worry too much about [enrollment].”

Cheng relates to her current position as a board member of Foothill DeAnza College. She says that there are ups and downs but it’s important that the leadership remains strong.

“I’ve seen it at Foothill DeAnza myself, I’ve been there for dozens of years and we’ve been through ups and downs and we are [also] in a down,” Cheng said. “When you have that challenging time of the more austere, difficult budget. Difficult enrollments that feed into the difficult budgets, then you have to make some tough decisions and it is not easy. But the elected body is elected to [make tough decisions].”

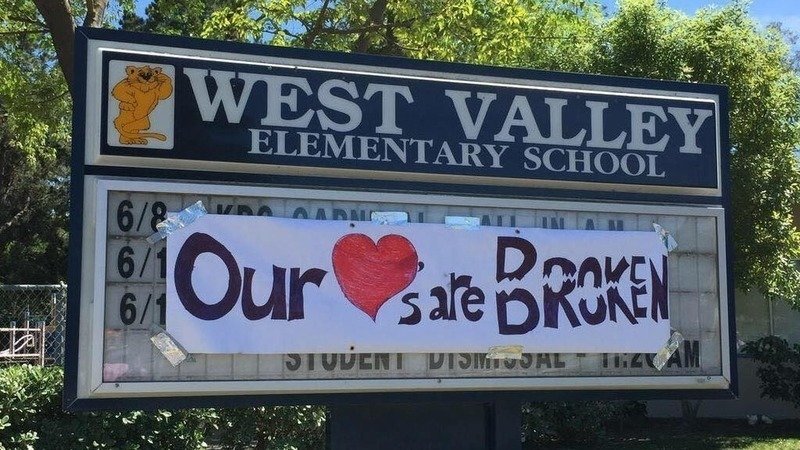

West Valley Elementary School parents and students were shocked after every staff member was reassigned.

Part 2: The tide turns

Exploring the start of declining enrollment and the community’s loss of trust in the CUSD board

By 2012, CUSD superintendent William Bragg had been retired for six years and CUSD’s phase of growing enrollment was starting to slow. Vogel, along with the rest of the board, appointed Wendy Gudalewicz as superintendent in 2012, replacing Phil Quon.

“We were looking for someone who was really strong in the curriculum,” Vogel said. “We hadn’t adopted new material in various areas for a long time. Our whole curriculum had gotten a little bit stagnant and we wanted somebody who had some expertise there.”

Gudalewicz believes she accomplished this by implementing new standards and curriculum in literature and math.

“I think changing some of the way teaching and learning happened [was] a major focus for us,” Gudalewicz said. “Getting technology up and running and in kids’ hands, the one-on-one iPad was another big accomplishment. But I think most of [our success] was a big shift in the culture of teaching and learning.”

Along with modernizing CUSD’s curriculum, however, Gudalewicz faced declining enrollment. In 2014, CUSD saw its first year of decline, but Gudalewicz says that certain board and community members were unresponsive and would not acknowledge the idea of declining enrollment. Gudalewicz believes that Cupertino City Council member Liang Chao and other community members fought the idea.

“I went out and shared [the information] with the community [and] every single school shared with [the community] that there’s a declining enrollment, which means you’re going to have declining revenue,” Gudalewicz said. “Every time I would go out, the group would say that we were making it up, that there was no decline. Liang [Chao] herself fought it, she said I was making it up, it’s fake, [that] there’s no decline in enrollment and there obviously was.”

Chao disagrees that Gudalewicz was transparent with her and the community. She also adds that she believes that declining enrollment was good for CUSD, stating that schools are currently overpopulated and notes that under Gudalewicz and other CUSD superintendents, the budget had increased every year. Board members say that schools using portable classrooms are not overcrowded as the majority of portables used at the time were not meant to move and that funds increase yearly because of the state’s Cost of Living Adjustment which adjusts funding to schools year to year.

However, Gudalewicz’s most controversial and upsetting decision to parents was her handling of the West Valley Incident, in which teachers at West Valley were all told that they would have to reapply for their positions. No teachers were rehired. Craig McPherson, a parent of two West Valley students, describes the West Valley incident from a parent’s perspective.

Gudalewicz says that she stands by her decision to not rehire any teacher to West Valley because she believes it ultimately benefited the school.

“There [were] some things that were happening at that school site that were not good for kids and one of the things that I had said after we [changed West Valley] was [to] wait and see what happens,” Gudalewicz said. “I’ve looked back, I’ve seen what happened, [West Valley] became a distinguished school. So if someone wants to say that was terrible, I always say look what’s coming, look what’s coming of it and it doesn’t look to me as the school went backwards, it looks as if it’s gone forwards.”

In contrast, McPherson believes that the West Valley Incident was mishandled and could have been easily avoided. As a professional manager at AT&T, McPherson believes that better administration management could have solved the incident amicably.

“I’ve had many sales teams and service teams and sometimes people butt heads,” McPherson said. “You’ve got to be a strong leader to push forward and bring people back in and so forth. If you have a group like that and you don’t have that leadership, then yeah, things can kind of get out of control. Do I think that it was to the point where that entire school needed to be blown up? Absolutely not.”

McPherson adds that his opinion was shared by other parents. He believed that while there may have been issues in West Valley, there was no reason to completely implement a new set of staff.

“Talking to a lot of people [at the time], they just felt like here and there, there [were] some things, but nothing that you would ever think the administration would say, ‘This is so bad that everybody’s got to go,’ or everybody [has to] reapply,” McPherson said. “I think that if you have the right leader in that school, none of that would have ever happened.”

But Vogel disagrees, as her opinion at the time was that the board and Gudalewicz’s decision to disband the entire school was the best way to resolve the alleged infighting at West Valley.

“We supported that decision [but] in retrospect, looking back, would I have supported that same decision today? Probably not,” Vogel said. “But at that time, it’s all about timing, it felt like the right decision.”

Vogel also doesn’t agree with the community’s assertion that the West Valley incident was Gudalewicz’s fault alone. Vogel says that the decision to not give any teachers their jobs back at West Valley was a decision made by not only Gudalewicz, but also the rest of the board.

According to McPherson, the largest impacts of the incident were felt by the older students. However, he says that contrary to what some in the community believed, younger students did also have an understanding of what was happening.

“We had some of the protests or meetings down at the school and all the kids were down there,” McPherson said. “They were writing messages of thanks to their old teachers on the school grounds. And so I think some of them, especially the older kids, were really impacted.”

Vogel believes that, while she supported Gudalewicz’s decision, the decision turned the public against Gudalewicz. She believes they scrutinized every subsequent decision she ever made as superintendent.

“[West Valley] was the start of [Gudalewicz’s] downfall in terms of her image with the community,” Vogel said. “After that happened, the community began to nitpick. It was like everything she did, she couldn’t do anything right.”

Vogel believes that the public often overstepped with its criticism online and through social media, which she believed was unfair and uncalled for. But she maintains that the board, andat the time, never lost faith in Gudalewicz. It wasn’t until the winter that the board’s opinions on her began to split because of the community’s views on her.

Gudalewicz, on the other hand, does not believe that parents overreacted. She says that a level of concern comes with unexpected decisions.

“I think that there’s a level of concern anytime you have anything that happens that’s unexpected, you’re going to react that way,” Gudalewicz said. “It’s like the world right now when people work in an environment of uncertainty, what happens is people’s anxiety goes up and people have concerns — they push back.”

The CUSD board faced public pressure to remove Gudalewicz from office, which they eventually did by unanimous vote in 2017. Vogel, as one of the board members who voted for Gudalewicz’s removal, says that she only made the vote to remove because she wanted it to be unanimous. Vogel says that she had hoped to work with Gudalewicz in order to resolve the issues at hand.

“By March, it was a 5-0 vote to release her from her contract,” Vogel said. “I voted yes, to release her but the only reason I did that … was because I wanted it to be a 5-0 vote in the face of the community. I didn’t want the community to see the board as split.”

However, Vogel believes that some of the criticism was unwarranted and just outright mean.

“I just remember all the stuff on social media and all of the phone calls and emails about what a bad job [Gudalewicz] was doing and how awful she was for the community,” Vogel said. “Granted, she made some mistakes, but she really cared about kids and that’s what really mattered to me is that it’s about kids. I thought she was mistreated by the community so I think for her mental health and her own career, it was a good move for her.”

Gudalewicz accused board members at the time, but now accuses Chao, for spreading dissent among the board members. Gudalewicz also says that Chao did not give her a chance before starting to call for Gudalewicz’s removal.

Chao states that she was just doing her job, and she was just one board member who could only influence so much in the community.

“I’m just doing my job asking for things I think a board member should ask, and she’s unwilling to answer such questions,” Chao said. “But then I was one board member, I couldn’t remove her … I don’t feel [like] I’m asking for things that [were] unreasonable. So eventually, two of the other board members were the ones who also realized they would like to maybe have a change of leadership.”

Gudalewicz believes that although her tenure at CUSD was cut short, she had an “excellent evaluation before [she] left.”

“The board and I left on good terms,” Gudalewicz said. “It wasn’t a case where they thought poorly of me. It was more of, if you have conflict like that, at some point you have to be able to say how you’re going to resolve it and what you had was you had a group of people who decided they were angry with me and they were going to keep pushing and pushing until they got their way. That’s what happened. Plain and simple.”

Part 3: How schools are funded

Exploring how CUSD and other school districts in California are funded

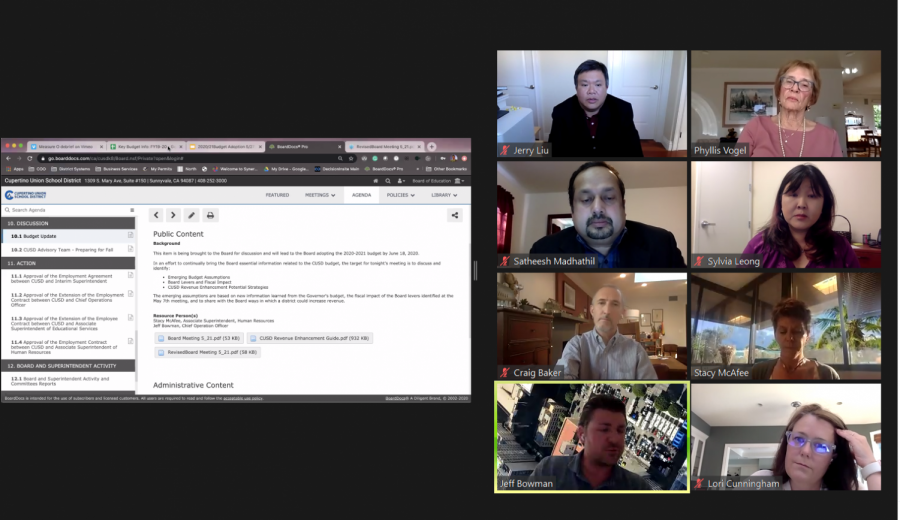

CUSD board members discuss options for budget cuts. The board meeting lasted over four hours.

In 2017, the CUSD board selected a new superintendent, Dr. Craig Baker. Board member Phylis Vogel notes the community was divided after the recent release of Gudalewicz and subsequently, Baker would have to resolve much community distrust, stemming especially from parents.

“The community was really split and divided and mad about what the district had done,” Vogel said. “They were angry with all of us. We wanted a healer. We wanted someone to come in and bring the community back together. We were being accused of lack of communication [and] lack of transparency. We had all kinds of anger leveled at the board and at the district.”

Additionally, Baker would have to resolve a new, more prominent issue: how to increase school revenue and decrease expenditures to prevent deficit spending.

Board member Jerry Liu explains that the state sets a level of funding per child at around $8,500 per year. Districts that fulfill the $8,500 per year per student through property tax do not receive funding from the state. Districts that do not do so receive state funding to compensate to meet the threshold. However, districts that exceed the $8,500 per year per student are allowed to keep and use any excess money, known as the LCFF model. Districts that are only funded to the minimum threshold created by the state are also known as the Basic Aid model.

Liu explains that the figure of $8,500 per year per student is changed yearly through the Cost of Living Adjustment (COLA) which California uses as an adjustment for factors such as inflation, cost of living and rising wages. While CUSD does not have a significant number of special education students, reduced lunch and ESL students, these figures also affect the COLA. Because of COVID-19, Liu says that California’s COLA for the next three years will remain stagnant, but board member Phylis Vogel argues that COLA has never been enough in Cupertino to begin with.

“COLA ends up being around two or three percent if [anything] at all,” Liu said. “Our operational costs increase by about 4% a year … COLA is another unreliable source [of money] for us because the legislature just decided every year what the COLAs are going to be and it’s never enough to cover our operational costs.”

In 1978, Proposition 13 froze all property tax assessments at the assessment value of the property in 1978. Unless the property was sold, the property received a 2% annual increase. This freeze in property tax hurt many school districts, keeping LCFF funding at 1978 levels until businesses and homes were sold.

In 2020, voters in California voted on Proposition 15, which would make commercial properties exempt from Proposition 13, meaning that their property would be taxed at market value. Proponents argued that this would provide billions of dollars in increased funding for government services and schools; however, Proposition 15 failed to pass with California voters. Liu says that if Proposition 15 had not failed, it would have given CUSD approximately eight million dollars of additional revenue that could have offset its seven million dollar deficit spending.

“It’s a hard question to answer because numerically you could … say that you are looking to take five to seven million dollars out of the facilities and if you got another eight or nine million that could have plugged that hole,” Liu said. “But then we have other needs. For example, we haven’t adjusted the salary for our employees since 2018. So then the question is, ‘Do you want to use [the money] to prevent school closures or do you use some of that, for example, to give raises to the teachers?’”

With the failure of Proposition 15, CUSD continues to be a school district reliant on Basic Aid from the California government as property taxes are not enough to fund the district. Former superintendent Dr. William Bragg argues that schools that are growing are always better off than schools with declining enrollment.

“One of the things that happened based on the way schools are funded, [is that] if you’re a growing district, you are financially much better off than if you’re declining,” Bragg said. “That’s because the increased revenue you receive through increased students, not all of that has to go to pay for the teachers and the cost of educating kids. A lot of that can go to [other things such as] infrastructure.”

But Vogel says that the financial issues of CUSD are not just a current problem, and argues that many of the financial issues of CUSD have been persistent throughout the years.

“There have always been financial issues in Cupertino,” Vogel said. “The big downturn in 2008 — we were recovering from that [and] the state was helping us out a little bit. By comparison to other times in our school district I would say [the 2010s] were good years for us.”

With declining enrollment, Liu argues that a combination of various cuts and an increase in other revenue outlets could prove to allow CUSD to become more financially solvent. A potential solution could be to receive more donations. CUSD Board member Lori Cunningham says that she has witnessed a lack of knowledge within the community about CUSD’s financial situation, which may affect the funding for the solution.

“They didn’t believe it,” Cunningham said. “They [say] ‘What do you mean Cupertino is low funded? Cupertino is not low funded. Cupertino is one of the Silicon Valley [school] districts.’ And it’s like, no, no, Cupertino is one of the lowest funded districts in the state.”

Liu acknowledges that CUSD raises significant amounts of money, but he notes that most of those funds raised are for individual schools, not for the district as a whole.

“[Donations to individual schools] doesn’t really help us with things like keeping the lights on and paying the teachers and all [and] that because that’s not what that money is for,” Liu said. “We’ve tried district wide donations — that hasn’t really [worked]. I think last year, the donations were in the hundreds of thousands. So it’s magnitudes off, because we’re talking millions and tens of millions here.”

Liu adds that there is a misconception throughout the community and corporations that CUSD generates revenue from Apple Park. However, the location of Apple Park falls outside CUSD boundaries, meaning that its property tax funds the neighboring Santa Clara Unified School District. Cunningham says that corporations are looking to make donations to school districts that are more historically disadvantaged.

“I think when they are looking to make large charitable donations, they are often looking to fund projects and programs for people and things that truly are for a very disadvantaged youth,” Cunningham said. “School districts that have really high numbers of high needs students, where you have high numbers of kids coming to school every day hungry, high numbers of kids coming to school every day from, you know, families where mom and dad are working two and three jobs around the clock.”

Used with Permission from the Regnart PTA

The Save Regnart car rallies drew support from students and parents alike.

Part 4: CUSD board and community members address the possibility of school closures

Exploring CUSD’s potential school closures and its impact on students, parents and teachers.

As parents logged on for the monthly board meeting to see how the CUSD board would resolve the district’s financial situation, The Cupertino Advisory Committee, a group of community members who advise the board, proposed a plan to make the district solvent again. It would require school closures.

In response, community members protested, making signs reading “Save Regnart” and “Save Cupertino Schools.” Regnart PTA board member Yari Toleno says that her first reaction to the possibility of school closures was “frustration, sadness and anger,” adding that she believes the closures would cause confusion among students.

“If Regnart would have closed during this pandemic, I really don’t know how the students would have taken the news,” Toleno said in an email. “The last eight months have been hard enough for these kids, to compile a school closure on top of all of their worries would have been quite catastrophic in my mind.”

As a result, car rallies were planned to voice opposition to the board’s plan, which Toleno believes was necessary in order to raise awareness about the situation.

“The car rallies and protests were a prime example of what every citizen should do if they feel the need to be heard,” Toleno said in an email. “Sadly, we tried the ‘email/phone call route’ and no one was listening to us. We then decided to mobilize and make sure our community was made aware of the proposed closures. The Save Regnart Campaign quickly grew within two days and we had hundreds of community members joining in on our rally cry.”

Board member Jerry Liu says that he and the board are committed to trying to keep all CUSD schools open, but that the board must keep its options open. He believes that in a financial crisis, the district will do what they have to to keep the district solvent, even if that requires closing schools.

“I believe, fundamentally, the problem with this district is we’re underfunded,” Liu said. “That’s why we can’t take [school closings] off the table. But I’m willing to commit as a board member, and I will very much advocate for, [that] we don’t just say, ‘Oh, [we will run out of funding in] three years, let’s worry about in three years’ but [instead], really actively work on it.”

Liu believes that as of now, the board will make decisions about closing schools based on the environment of the school.

“There is a difference between closing schools because you need the money versus closing schools when the learning environment has gotten bad for the students,” Liu said. “I think right now, I don’t believe we should run schools with one class per grade. I think that’s just not a good environment for the kids. It’s not a good environment for the teachers.”

According to Liu, one possible solution is to allow parents to choose what elementary school to send their child to instead of requiring parents to send students to their local elementary school. Liu argues that this will help fix the current enrollment disparities at different schools.

“Right now we have these alternative programs — we have Faria and McAuliffe, Clip and [Murdock Portal],” Liu said. “They all have long waiting lists … I think there are incentives we can put in place to have [school sizes] balanced out. But we need time — it’s not something we can do right away.”

With the addition of these alternative programs, Liu hopes that the community as a whole will choose to pass parcel taxes that will help the district, as the district doesn’t have many options left to combat the issue.

“[If] the community can pass this parcel tax, we will commit to work with the community to put these things in [and] make it all transparent,” Liu said. “Right now, you can’t even find out how many kids [your school is] up to. I would, at least for my part, advocate for making that information public so [people] know what the metrics are, what their actions were doing and where we are today. [That way] it’s not going to come as a surprise in 2023. People [won’t] go, ‘Oh my God, what’s going on here?’”

Board member Lori Cunningham believes that because of the community’s reluctance to discuss school closures, the board is unable to affirm that schools will stay open.

“We are not at the point where we can say [that any school is safe from closure] because we never got to that point in the conversation,” Cunningham said. “I think that the community really was not comfortable with any of the conversation that was happening and did their best to stop the conversation happening about certain school sites.”

While Toleno sees the challenges of the current budget situation, she believes that better avenues should be pursued in order to prevent school closures. She thinks that the board should improve communication about financial issues and the boards plan.

“Many parents and community members are not aware of the dire straits CUSD is in currently,” Tolene said in an email. “People assume we are a ‘rich’ community with the best schools, so there is no way that the schools are [facing] financial issues. The disturbing fact is that they are wrong. Granted, most of Cupertino is in an affluent community, but not every neighborhood reflects that.”

Vogel believes that community involvement in decisions of CUSD depends on what is being discussed, noting that school closures are an eye-catching move that parents would want to be involved in.

“I think the issue of school closure has brought a lot of people out who maybe even though they had kids in our district, maybe they weren’t paying attention to the district, maybe they were only paying attention to their own school,” Vogel said. “Now, there’s a huge level of involvement and I think … no matter what we do, we will not make anybody happy, we all know that. I think it’s our responsibility to listen to them and if a decision is made to close schools, I think we have to really involve the community.”

However, on Nov. 12, parents declared “victory” when board members decided to table the decision to close schools until later. In the meantime, the board is asking the community to help pass a parcel tax in the upcoming 2022 election. According to parents, this would resolve their objection to closing schools as well as help fund the district. Despite this, Vogel notes that school closures remain a possibility in the future, adding that closing schools will never be an easy decision.

“It’s an emotional thing to close a school — it’s tough,” Vogel said. “Not only in the decision of what to close, but also in the decision of how to move forward and help the communities move forward.”

—

In the 1970s, CUSD experienced a gradual decline and later a rapid increase in enrollment. Through the work of Dr. William Bragg and board members around him, CUSD opened new schools including Lawson Middle School. The 2010s came with declining enrollment, spurring community distrust between administration and the public and finally, reaching the depths of deficit spending. As parents and community members rallied around schools to save them from possible closures, a variety of methods were suggested attempting to save CUSD’s solvency, and some implemented. Former board member Pearl Cheng summarizes the life of our local public school district.

“Our community will come out strong — it always has through these times of up and down,” Cheng said. “I think we just have to know that and be able to support that as difficult as some of these decisions.”