“Respect” to “WAP”: Examining the progress of women’s empowerment

Exploring the dichotomy of women’s sexual liberation presented by songs throughout history

Photo Courtesy of Atlantic Records

Megan Thee Stallion and Cardi B.’s hit single WAP is a boundary breaking anthem of women’s sexual liberation

October 12, 2020

I refused to listen to “WAP” when it first came out.

Released on Aug. 7 by Cardi B. (real name Belcalis Marlenis Almánzar) and featuring Megan Thee Stallion (real name Megan Jovon Ruth Pete), this song is a boundary-busting, comfort-crushing storm of not-so-subtle sexual innuendos. After its debut, “WAP,” which stands for “Wet Ass P*ssy,” the song rose to number one on the Billboard Hot 100 and broke the record for the number of U.S. streams for the first week at 93 million.

The three minute song is uncomfortable, unpleasant and unapologetic. Frank Ski’s “There’s Some Wh*res in This House” plays on a loop in the background throughout the track, adding a heavy bass that punctuates the exceedingly outrageous statements made by the rappers. Each line is explicit and each line explicitly mentions sex. The song was further popularized on TikTok by choreographer Brian Esperson with the creation of the #wapchallenge – a dance arguably more audacious than the song itself that had influencers from Willy Wonka to Addison Rae Easterling literally banging the floor to the beat of the song.

Despite its smashing success, however, I initially refused to listen to “WAP,” aside from the 15-second clips of the dance challenge that appeared on my TikTok For You page every so often. The song, in my opinion, was crude, obscene and had none of the meaningful lyricism and complex melodies that my usual taste in music did. Much to my chagrin, it was my mother playing the song in the car as I drove her to Target that got me hooked on the song. The fact that she, who was usually so quick to tell me to skip much less explicit songs, was singing along to “WAP” (granted with much censoring, but still, this is my mom) finally made me reconsider my initial perceptions of the song.

I started reflecting on the meaning behind the song — not what is explicitly conveyed by the lyrics, but rather, the deeper message regarding the female sexual liberation’s place in society, and how this song completely dismantles it. While hardly the first song that addresses sexual freedom, “WAP” is the first song to do it so audaciously — in fact, Atlantic Records, Almánzar’s signed label, initially asked her to put Pete on a different record because of the obscenities that occur so often in the song.

While the way in which women’s sexual liberation is referenced in the song is unprecedented, “WAP” is not the first song to have broken boundaries for women’s empowerment — it is difficult not to pay homage to Aretha Franklin’s “Respect,” a reimagined feminist and civil rights anthem released in 1967 that masterfully interplays upbeat jazz and powerful vocals to demand the listener give Franklin their utmost “R-E-S-P-E-C-T”. “Respect” also topped the Billboard charts, earned Franklin two Grammy awards in 1967, placed number five on Rolling Stone magazine’s list of “The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time” and was inducted in the Grammy Hall of Fame. I wanted to examine the musicality and lyricism used in both songs to explore how the idea behind “what women really want” has changed throughout the past few decades.

Before we start dissecting “Respect,” however, let’s set the scene: it is 1967. More women than ever before are entering the workforce, but the average woman’s salary is 60% that of her male counterpart. The Equal Pay Legislation was passed four years ago, but even so, most low-paying jobs are classified as female. Nevertheless, feminism continues to make leaps and bounds, from the federal government approving a birth control pill in 1960 to the formation of the National Organization for Women in 1966.

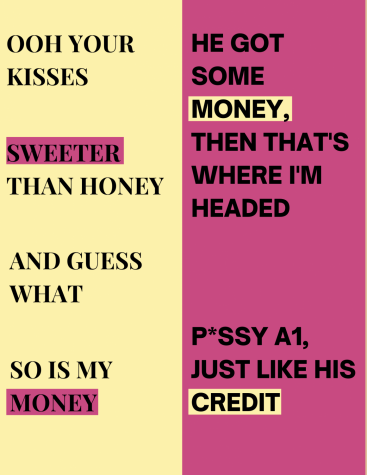

Otis Redding wrote “Respect” in 1967 as a desperate plea to receive respect from his woman at the end of a hard day where Redding is constantly degraded for being a Black man. Franklin completely flipped the message of the song, instead demanding respect from a man after she earned her own money. She references her independence with lyrics like, “Ooh, your kisses / Sweeter than honey / And guess what? / So is my moneylisten,” intertwining physical pleasure with her own financial freedom. This intersection of money and sex is also explored in WAP, but through a lens more representative of a ‘gold-digger’ through lines like, “He got some money, then that’s where I’m headed / P*ssy A1, just like his credit.listen” While these two lines appear to express nearly opposite ideals, relative to the time period, they both create the same kind of discomfort for the listener. Franklin demands that her listener stop assuming that only a man can make money, come home and then be kissed sweetly by their spouse — a deeply-ingrained American ideal at the time. And even though Almánzar appears to be reversing that ideal by referencing a man’s money rather than her own, she is also empowering women to do what they need to secure that financial freedom that Franklin so revered.

“WAP” has received heavy criticism for lyrics that appear to accept traditionally assigned gender roles. Many state that it fulfills the “patriarchal bargain,” the idea that women deal with the societal constraints placed on them by using gender roles to their advantage — often seen with women playing into the concept that “sex sells.” “WAP” undeniably uses sex as a selling point — it is, after all, the entire point of the song — but the song doesn’t try and exploit the system or encourage women to start objectifying themselves. It instead allows women to look beyond the objectification and contrasting ideals from a patriarchal society that tell them they are either nothing more than their bodies or that they should cover themselves up in order to deserve respect and simply feel, well, sexy.

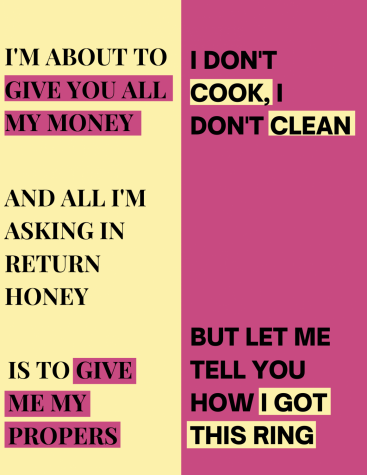

Similarly, Franklin also explores the intersection of gender roles and money with the lyrics, “I’m about to give you all of my money / And all I’m askin’ in return, honey / Is to give me my propers,listen” by again dismantling the idea that she needs a man’s money and instead asks for her “propers,” or mutual respect. Almánzar shatters gender roles less subtlety with the lines, “I don’t cook, I don’t clean / But let me tell you how I got this ring,listen” showing how she can break the mold of the traditional woman while still achieving idyllic milestones like marriage.

Franklin, Almánzar and Pete all reference largely similar gender roles and feminist ideals in their songs, but the way in which they encourage their audiences to interrupt these ideals is what is most telling about the progression of feminist movement over time. While Franklin demands respect with her powerful lyrics and captivating interplay of blues and jazz, Almánzar and Pete make it clear with their unapologetic bass and explicit bars that they don’t care if you respect them or not.

Cardi B & Megan Thee Stallion are what happens when children are raised without God and without a strong father figure. Their new “song” The #WAP (which i heard accidentally) made me want to pour holy water in my ears and I feel sorry for future girls if this is their role model!

— James P. Bradley (@BradleyCongress) August 7, 2020

In short, “WAP” is empowering because it opposes every traditionally enforced societal expectations. It objectifies women and takes power from it anyway. It shows society that despite the fact that women face obstacles at every turn, women can be empowered and love their bodies even when they are constantly degraded for doing so.

Here’s the thing. You may not like “WAP.” Listening to “WAP” may make you want to “pour Holy Water in your ears.” But whether you like it or not, there’s no denying that Cardi B. and Megan Thee Stallion have absolutely redefined what it means to own it.