Members of the MVHS community use their voices in audiobooks and commentating

Ways in which the MVHS community uses its voice aside from speaking

December 17, 2019

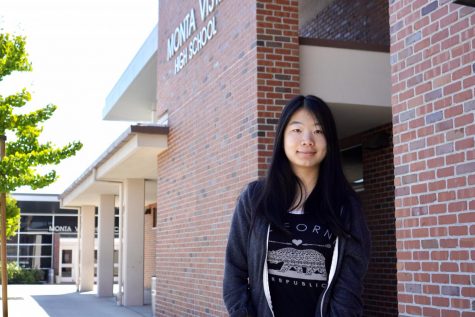

Junior Austin Ota had been interested in becoming the football announcer in hopes of gaining experience, as he aspires to go into professional sports broadcasting in the future because of the potentially high salary and added benefit of watching and talking about sports for free. He had considered getting more involved in commentating for MVHS games for a while, but he didn’t have the guts to make the move.

Finally, he talked to School Financial Specialist Calvin Wong, who sent him to Athletic Director Nick Bonacorsi, who sent him to business teacher Jeff Mueller. He got the position, and went in for his first game on Sept. 13 against San Jose HS.

In terms of preparing his voice for broadcasting, Ota has never had professional training. However, he takes voice lessons for singing, and his vocal coach emphasizes proper vocal technique of placing words in the front of the mouth, similar to the feeling of clenching the teeth and saying “e,” even in everyday conversation.

“But I kind of threw that all out the window,” Ota said. “When I started calling football games, it was a lot easier for me to just be loud and big, rather than focus on technique.”

However, Ota was able to make use of his theater experience and apply those skills to commentating.

“I think a lot of it is nerves and I think a lot of people would get kind of nervous doing it, but I just have fun with it,” Ota said. “I think it’s good because I don’t have any stage fright just because I’ve been doing it for so long.”

MVHS alumna Amita Mahajan used her eight years of training as part of Speech and Debate during high school and Mock Trial in college when making audiobooks, putting recordings of herself reading books on YouTube. However, she still emphasizes that professional audiobook readers have multiple years of training.

“A lot of professional voice narrators and people who read audiobooks go to official classes, and they do training and things like that,” Mahajan said. “So I’d say that that process takes years, and it’s a matter of continually trying to make yourself better and gain more skills.”

Mahajan began making audiobooks in middle school and her YouTube channel quickly grew, with over 4.7 million views and 13,400 subscribers. She currently works as a voice actor for Learning Ally, a nonprofit for students with physical and learning disabilities, and Audible, where she has recorded the audiobook of “The Enneagram Types” by Lawrence Williams.

Literature teacher David Clarke has also made an audiobook for his students, as he understands that audio learning may make it easier for some students to grasp the material. In addition, Clarke teaches a sheltered class where students are learning English, so the ability to read and listen at the same time becomes very important for them.

Clarke has been able to find already existing audiobooks for most books his students read, whether self-recorded ones on YouTube or commercial recordings on Amazon or iTunes. However, the specific translation of “Crime and Punishment” AP Literature was reading had no existing audiobook, so Clarke recorded one himself.

“The only preparation is I’ve read the book at least half a dozen times,” Clarke said. “So I have a pretty good idea of the way the language works in this particular translation. And I know the plot and the characters. All I did was I just turned on the recorder and recorded myself [reading] the book.”

Mahajan also emphasizes the importance of knowing the material, which enables her to plan elements like what kind of voices to give certain characters. For example, if an audiobook recorder gave a character a Southern accent without realizing that the character would be a prominent one due to lack of preparation, they would then have to speak with the accent for chapters on end.

“For a given book, you should definitely read the entire book beforehand so that you know who all the characters are, where all the dramatic parts are, if there’s certain sad scenes,” Mahajan said. “You usually have to mark all of that down … Generally a lot of people either start a Word doc or a Google Doc or something and take notes on specific things that they have to keep note of, or you can do it in Apple Reader and just add comments in the side and highlight.”

Clarke, on the other hand, does not give particular voices to characters, and he feels that the way he speaks in audiobooks is similar to how he would normally use his voice.

“I read to [my students] a lot,” Clarke said. “I mean obviously I have a style when I’m reading. [However, it] didn’t feel like a different experience. I’ve read it so many times I hear [my] voice in my head … I’m sure some of [my students] hear my voice when they’re reading after they’ve heard me.”

While Clarke’s voice does not differ significantly from reading audiobooks to speaking normally, Ota thinks there is a notable deviation in his voice when commentating during games — lower and more “grumbly.” He tries to vary his voice depending on the importance or outcome of plays.

“I like to get the crowd hyped, [although] it doesn’t always work,” Ota said. “What I’ve learned is that on bigger plays to call it differently than just a regular boring tackle. So, I was going from doing the exact same big yells on every play, and I’m trying to cut down on that to make it easier to get the crowd hyped during the actual times that that need hype.”

Ota loves commentating, as he has been doing theater for 10 years and enjoys hearing himself and his voice being loud. Meanwhile, Mahajan was not particularly aware of the implication of her voice being out and accessible on the internet when she first started.

“YouTube gives you analytics and per those, as according to them [there are people in] about 150 countries who are listening to your voice,” Mahajan said. “I think it’s fascinating to think about that there’s millions of people out there who’ve heard them speak. You’ve never seen them. You’ll probably never meet them and yet they’ve heard your voice and you’ve basically read them stories.”