Textisms act as communication cues

The language of text messages acts as communication cues

November 20, 2019

The first text message, sent in 1992 by Neil Papworth, sparked a new form of communication. Since then, texting has grown in popularity, with Americans sending and receiving more texts than phone calls for the first time in 2007, according to the Nielsen Company. Texting, as well as the emergence of instant messaging platforms like social media, has shaped how people communicate through textisms — abbreviations, acronyms and irregular punctuation or capitalization.

Binghamton University professor Celia Klin, who studies psycholinguistics, has researched computer-mediated communication, specifically text messages. At a lab meeting, an undergraduate student who worked in Klin’s lab questioned if the way people read formal language, like articles or stories, differs from text messages, sparking a new research topic for them.

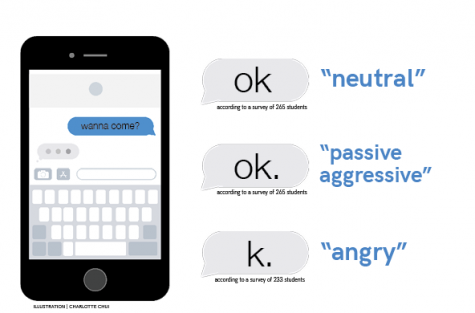

In the resulting 2016 study, 126 Binghamton University undergraduates were presented with either text messages or handwritten conversations, where the sender asked questions, such as “Dave gave me his extra tickets. Wanna come?” The responses, such as “okay” or “yup,” either ended with no punctuation or with a period. Then, participants were asked to rate the response’s level of sincerity. The research found that text messages with a period were perceived as less sincere than texts without punctuation.

“What was most surprising to me was that our research subjects were so tuned in to tiny, tiny differences,” Klin said. “They were just reading them fast. You know, they’re there because it’s part of a class requirement. They weren’t super invested. They were just reading them through, rating how sincere they thought they were, and that tiny difference made a difference on how they interpreted it.”

However, the handwritten conversations received similar sincerity ratings, regardless of whether or not they included a period at the end. The study speculated that this was because “the exclusion of periods in text messages is the default.” Junior Jamie Lau agrees with this speculation and how it affects her interpretation of texts. She points out that because the norm is to text without punctuation, adding punctuation can change how the text is perceived.

“[With a] period means they took the time to actually put the period,” Lau said. “So it’s like they’re more serious or mad or something.”

Junior Meghana Dhruv also notes that due to a mutual understanding of the connotations behind punctuation in texts, using punctuation is a way to consciously signal emotions.

“‘Okay’ with a period means they want you to know that they’re mad at you, but they might not actually be mad at you,” Dhruv said. “But they just want you to know. They want you to think about it. Pettiness.”

Junior Brooke Young believes the context behind who’s sending the text and their typical form of texting language also affects her interpretation of it. For example, the norm for Young’s parents is to text with proper punctuation and grammar.

“Parents usually add things like exclamation marks and periods as they are used, but if we do it, people will think about it a different way,” Young said. “If your friends send you ‘okay’ period, they’re definitely mad. There’s no question about it. But if their parents do it, they’re just saying okay.’”

While Lau, Dhruv and Young point to generational differences in how their parents text versus how their friends text, Klin believes the distinguishing factor may be familiarity or experience with text messaging, not necessarily age.

“People who were less tech-savvy or tech fluent might have not noticed a difference between a period and no period,” Klin said. “These were 18, 19-year-olds, who not surprising, spent a lot of time texting and have been doing so on other sorts of social media. They certainly spent a lot of time and were quite fluent.”

When Klin published the paper, she says it was met with people who were “weirdly outraged” by the findings, leaving comments saying that they wouldn’t put up with it if their kids started writing like that. Some critics have also expressed beliefs that texting is “sloppy, lazy communication” or “penmanship for illiterates.”

“I totally disagree,” Klin said. “From the beginning of time, you can find these quotes 500 years ago and 1,000 years ago of people saying the way that people use language now is wrong and sloppy. People have this odd sense that whatever language looked like when they were growing up, that [is] how language should be.”

Klin believes that the nature of language is that it changes with the times, and texting, as a form of language, is another manifestation of those changes.

“Language is always evolving,” Klin said. “You read Shakespeare, and you realize how dramatically language has changed since then. I picked up an old novel — not that old, like the 1960s — when I was on vacation, and I was amazed at how stiff that language even seemed. But language evolves, so there’s no reason why written language shouldn’t also evolve.”

Though texting is a form of written communication, the quick back and forth makes it like a conversation, according to Klin.

“A lot of the things that we convey in a conversation, we do, not just with the words we use, but in our tone of voice, the way we pause, the ups and downs with our voice,” Klin said. “It’s really a big part of how we can make meaning. So here we are in the situation where people were having almost a conversation, and they were missing all of that eye contact, tone of voice. So what do people do? They very quickly found ways to add in some of the things that they are missing.”

For example, one Twitter user commented, “See also the ways in which we emphatically add our agreement, the different ways in which we *emphasise* the important or mock the ~important~, express our utter suRPRISE, and use emoji to better convey tone with concise language,” while another tweet pointed how they “use capitals to emphasize The Point [or] use extra letters or characters for emotion!!!!!”

An article by The Outline also noted how older generations tend to use excessive ellipses. While some Twitter users say they interpret a text message of “ok…” to have a connotation of “Are you kidding me?” or that the sender is mad, NYU professor Eliot Borenstein told The Outline that he uses ellipses as a trailing off of thought, unlike the hard stop of ending a sentence with a period.

Dhruv, however, comments that she and her friends don’t use ellipses. Similar to some Twitter users, who have also noted the generation gap in ellipses use, ellipses are something Dhruv sees more frequently in older generations. Instead, Dhruv uses comma ellipses in messages like “ok,,,” as “an extension of thought,” indicating that the conversation isn’t over or that she wants the other person to respond.

“I feel like it points to how creative people are,” Klin said. “So I’m all for the changing of language, and I think the reality is, most people know when to use informal language and people know when to use formal language, right? We don’t text the same with our friends as we would with a professor. I think having that kind of informal language, with our punctuation and things like that, I actually think it serves a purpose. Language is to communicate and it helps us communicate.”