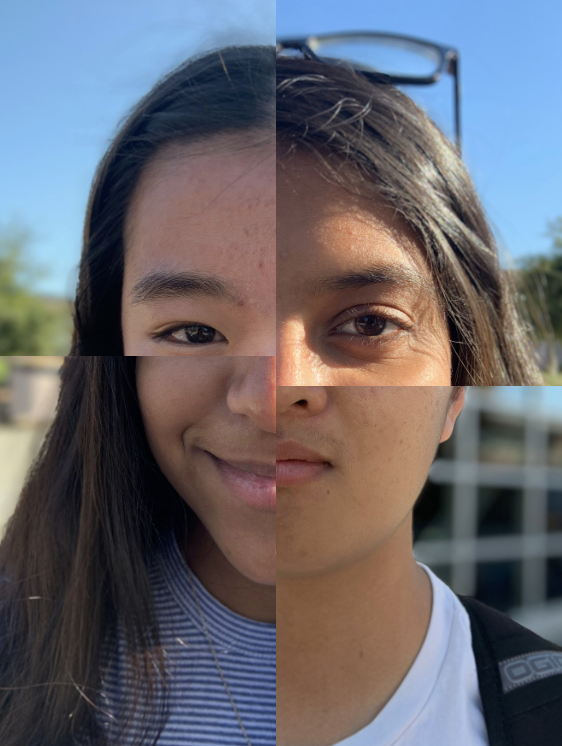

The skin we live in

Students deal with the struggles presented by their skin

September 27, 2019

Pale Means Pretty

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, light skin has been a sign of wealth and class since the Han Dynasty in 206 B.C.; only the rich could afford the luxury of staying inside. Dark, sun-burnt skin was associated with the outdoor toils of the poor. Royals and nobility would escape no lengths to whiten their skin, avoiding the sun like the plague and using white powder on their faces to appear more pale.

Centuries later, this standard of beauty began to fade. With the rise of the second industrial revolution in the 1920s, pasty skin became associated with factory workers while the rich flaunted sun-kissed skin. In the West, “beautiful skin” was defined as a golden complexion.

However, the desire for darker complexion did not extend to the rest of the world, as most Asian nations continue to hold milky white skin to a higher standard. Perhaps the most prominent example of this phenomenon is South Korea, where the skin-lightening industry is worth an estimated $13.1 billion, according to CNN.

Sophomore Madeline Choi experienced South Korea’s obsession with pale skin first-hand until she moved to Cupertino when she was 12.

“Honestly, [in] most Asian countries including Korea, pale means pretty,” Choi said. “I don’t know where that comes from. But pale automatically means pretty. That doesn’t mean we had a fetish to become white. Just that pale skin in general meant more beautiful.”

Despite being exposed to Korea’s infatuation with light skin from an early age, Choi didn’t start to internalize Korean beauty until after coming to the U.S. During her freshman year, she developed a bout of acne that covered her cheeks, forehead and chin. Her awareness of her skin suddenly sky-rocketed, and with it, her attention to the Korean beauty industry and its standards.

“Freshman year I broke out really violently,” Choi said. “I don’t know why; I wasn’t stressed, nothing really changed, I think it was just hormones. But I broke out so badly, and that’s when I started noticing like, ‘Why do Koreans have such good skin? And why is it only me that doesn’t have good skin?’ But freshman year is when I started watching Korean YouTubers and got more interested in Korean makeup and everything like that.”

The irony of starting to pay attention to Korean skincare two years after moving to the States is not lost on Choi. She uses it as evidence of her strong preference for Korean beauty standards despite living in the U.S. for her teenage years.

“I didn’t really notice a big shift in standards when I came here per se because I still have the same standards for myself,” Choi said. “I still found pale skin to be more appealing on myself. I used to be seriously pale when I came to the States, and sometimes I want to go back to that, which means that that standard is still in me.”

The standards of beauty that Choi encountered in Korea were a set of extremely rigid, set laws that did not leave room for a single pimple or blemish on one

Choi explains that Korean beauty standards are extremely narrow – a single mark or blemish can completely change how someone’s skin is judged. For her, coming to the U.S. allowed her to gain exposure to a set of beauty standards that extended over a much wider variety of facial imperfections.

“For Korean beauty standards in general, and even specifically for skin, they have a set standard — if you don’t have glass-clear skin, then your skin is not good,” Choi said. “And I feel like in the States, the beauty standards are way wider. One blemish on your face does not define whether your skin is bad or not. I’ve seen YouTubers embrace their beauty marks and actually accentuate them, and that’s something that you would never see in Korean beauty.”

The past three years in the U.S. have allowed Choi to redefine her own standards of beauty. Choi still identifies with a lot of the standards set by the Korean skincare industry, but her exposure to Western beauty ideals has had a largely positive impact in her acceptance and comfort of her own skin. Despite her issues with acne, blemishes, and gaining a tan over the past couple of years, Choi feels comfortable in her skin, a privilege she knows she would not have had in Korea.

https://cdn.knightlab.com/libs/juxtapose/latest/embed/index.html?uid=da6a050c-e1a5-11e9-b9b8-0edaf8f81e27“Honestly, what I considered to be beautiful skin really did change,” Choi said. “Because I feel like if I had the same problems in Korea, if I broke out that badly in Korea, I would feel way worse than I did here. But here, I don’t really care about the blemishes on my face as much as I would have in Korea, because everybody has it.”

For Choi, approaching the point where she is able to allow American and Korean beauty standards coexist within her peacefully has been a process, but she feels that having the experience of being exposed to two drastically different standards of beauty has had an overall positive impact on her.

Pimpled Problems

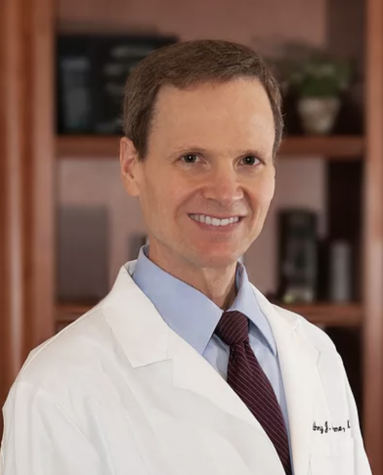

According to dermatologist Dr. Anthony Badame, acne is caused when hair follicles on the face, chest and back get blocked with oil. It appears as blemishes, red spots, blackheads, whiteheads or cysts. Because of the rollercoaster of hormonal changes experienced by teenagers during puberty, acne tends to appear around teenagers’ middle of high school years.

Senior Rishabh Ranjan first developed acne when he was around 12. He explains that after developing blemishes on his face, he became significantly more aware of his skin.

“I didn’t really care that much at first, but having pimples can be really painful. It really hurts sometimes,“ Ranjan said.

Having acne affects teenagers in a wide variety of ways, Dr. Badame explains. In his patients, he notes that teengares with acne are often more conscious and insecure about their skin.

“There are a lot of social and psychological ramifications of having a lot of acne and having to go to school everyday,” Dr. Badame said. “A lot of [teenagers] try to cover it up and are socially withdrawn from their peers.”

For Ranjan, his personal struggles did not end with the pain caused by his acne. He explains that he was also teased by his friends when he first started to break out.

“Some of my friends pointed it out to me as well, and that was really hard because it made me more self-conscious and insecure about having acne in the first place,” Ranjan said. “After developing acne, I started looking in the mirror more and I’d notice these red spots on my face. I used to get really stressed out about it, but that stress would just make my acne worse, so I had to get better at dealing with my insecurities about having acne.”

However, Ranjan has been able to get more comfortable with having acne over the past couple of years. Using his creativity, he decided to grow a beard to deal with his insecurities and become more accepting of the blemishes on his face.

“I really like having a beard – I think it’s manly, but it also helps cover parts of my skin that I feel insecure about,” Ranjan said. “I feel like it focuses attention away from my acne, so I kind of use my beard as a way to deal with the stress I feel with my skin.”

Similar to Ranjan, Dr. Badame sees many of his patients using makeup, hair and over-the-counter products to try and deal with their insecurities about their acne. He explains that dealing with acne is a process that has to do with self-acceptance, and one that cannot be rushed.

“Having acne, dealing with acne, it’s a journey,” Dr. Badame said. “Sometimes, it’s a journey that takes a year, and sometimes it’s a journey that lasts your whole life. But that’s all it is, it’s a journey. So if I could say one thing, it would be that acne is treatable, and that having it, it isn’t the end of the world.”

Dark skin makes makeup exploration challenging

Junior Sachi Roy first became interested in makeup when she was in sixth grade. Inspired by the intricate eyeshadow looks she saw on YouTube and other forms of social media, she wanted to try them out herself. But she quickly ran into what seemed like an insurmountable obstacle.

The colors didn’t show up on her face.

The foundation was too pale, the eyeshadow not pigmented enough and the blush seemed to disappear into the depths of her chocolate cheeks, leaving no trace. Like many other dark-skinned girls, Roy was forced to face the struggle of wearing makeup that wasn’t made for her complexion.

“When I started with makeup, I would only do eyeliner,” Roy said. “My mom tried to get me a foundation that would match my skin tone, but it ended up being way too light for me. And I didn’t want to look like a ghost when I was walking around school, so I would just put on eyeliner and I’d kind of ignore the fact that I have blemishes all over my skin. But there wasn’t really much I could do about that.”

Over the past decade, the availability of makeup in a wider range of skin tones has increased dramatically, most notably with Rihanna’s Fenty line housing an impressive 60 shades of foundation. However, Roy notes that despite the increasing acknowledgement of different foundation shades, most other products, including blush and eyeshadow, are made with lighter skin tones in mind.

One of Roy’s most difficult experiences with makeup was in eighth grade. After seeing what she describes as “a beautiful sunset eyeshadow look” on YouTube, she tried to replicate it, only to find it didn’t work. None of the colors appeared on her face the same way that they did on the fair-skinned girl in the video.

“I feel like that was a major setback, because that put this idea in my head that I would never be able to do those kinds of like complex looks and I would always be limited in what I could do,” Roy said. “So I just worked with natural colors then I didn’t even use eyeshadow.”

As the range of available foundation shades increased, so did Roy’s comfort in the color of her skin. Roy credits a part of her comfort in her skin color to the community she lives in, stating that being surrounded by people who looked like her definitely increased her confidence. However, she explains that she still struggled with the lack of representation of darker-skinned girls in the media.

“When I would go outside, I would see that my family and most of my friends are brown,” Roy said. “And I’d see that that’s kind of been the norm, so I never really thought about it when I was in school or when I was hanging out with my friends. But when I would go home and I watch TV shows like ‘Good Luck, Charlie,’ and everyone’s white.”

Along with her struggles finding makeup products that suited her skin tone, Roy explains that having a darker skin tone has affected how she edits pictures.

“I used to actually make myself look lighter,” Roy said. “I never really posted those pictures because I was really bad at editing, but I would always make myself look lighter. I don’t know why, I think maybe I thought it would brighten my skin.”

As Roy has grown more comfortable with the color of her skin, she explains how she has also abandoned the desire to make herself look paler in photos. Despite this, Roy explains that she still pays a lot of attention to how lighting affects the color of her skin in photos.

“Nowadays, when I take pictures, I don’t really edit them anymore, just because I feel like that’s not really authentic,” Roy said. “But I do struggle with lighting because if it makes me like if I look darker than I already am, then you can’t even see my features.”

Learning how to use makeup to accentuate her skin color has been a journey for Roy. But in spite of the ups and downs that come with having a darker complexion, she has come to love her skin.

“

,” Roy said. “And I don’t know, maybe that’s just me being biased towards myself, but I really do prefer brown skin on me.”