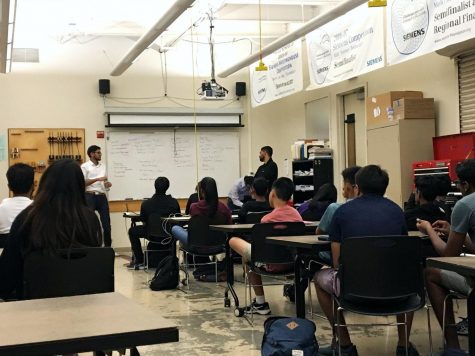

Monta Vista Robotics Team offseason trainings: a student-run experience with mentor support

MVRT alumni mentor the team in workshops to coach members on competition strategy

September 27, 2019

Monta Vista Robotics Team (MVRT) held its first of many off-season workshops supervised by mentors on Sept. 18. In the weeks before build season, MVRT received training from mentors who coach the team about the ropes of robotics — from competition strategy to robot design and programming. These mentors are not only experienced with working in the engineering industry — they were also members of MVRT when they were students at MVHS years ago.

One of the mentors who hosted the first workshop, Anant Singhania, was president of MVRT until he graduated in 2012 to pursue economics and mathematics at UCSD. Now a data analytics research assistant, Singhania has been mentoring the team since 2016. Throughout his interactions with high school students during the past few years, Singhania has observed experiences in MVRT members that reflect his own high school experiences.

“[I see] the way I was in high school in a lot of the kids the same way here,” Singhania said. “We’re fighting the same battles that I was fighting when I was in high school. As a student, it was really important in terms of being able to learn a lot of different skills, both on the engineering side and the soft skills in terms of leadership and communication.”

You’re interested in the team’s success, but you use that purely as a vehicle for the students to build confidence and get inspired about the program, and not so much specifically about only winning the competition. — Anant Singhania

However, some of Singhania’s mentalities about robotics have shifted since becoming a mentor, especially with regards to winning the annual For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology Robotics Competition (FRC).

“As a student, I was a lot more competitive about the program, meaning that I was really passionate about winning and doing really well,” Singhania said. “And now as a mentor, you kind of take a little bit of a 1,000 foot view, per se — you want to see students succeed. You’re interested in the team’s success, but you use that purely as a vehicle for the students to build confidence and get inspired about the program, and not so much specifically about only winning the competition.”

Robotics mentor and engineering teacher Ted Shinta shares Singhania’s sentiment regarding prioritizing personal success over winning the competition.

“To me, the welfare of the students is the first thing,” Shinta said. “I could care less about winning or anything about that. I’d rather have no team if students are being hurt by there being a team.”

In addition to maintaining student welfare, Shinta defines his role as the mentor for the team to being primarily concerned with machine safety, preferring a hands-off approach with mentoring the student-run team.

“Because [alumni] worked as part of the team before, they have fully bought into that [hands-off] system,” Shinta said. “Generally the students recognize that these guys do know something so they’re willing to listen to them.”

Shinta’s familiarity with the alumni provides him with more confidence in the mentors than others without as much experience with the inner workings of the team. However, when mentors aren’t experienced with MVHS students, conflict regarding mentor control arises.

To me, the welfare of the students is the first thing. I could care less about winning or anything about that. I’d rather have no team if students are being hurt by there being a team.

— Ted Shinta

“For adults [there] is this thing of being able to relinquish control to the students, to let them make mistakes [and] actually have control — not to say, ‘I want it this way, you have to do it this way,’” Shinta said. “Instead, saying, ‘This is my suggestion, but if you choose something else, I’ll support you on that.’”

Likewise, Singhania supports the team’s freedom of choice and independent nature, believing that mentors should focus on making knowledge available to students so that they can explore wider applications of concepts.

“We kind of just want to get the kids to think a little bit about these topics,” Singhania said. “There isn’t really a direct action item to say, ‘We want you to build this specific thing, we want you to implement this program.’ [We want to] take some of the more advanced concepts and get the kids to think, maybe there’s some point in between the most advanced concept and where we are currently working towards.”

Senior Chelina Wong, who has been on the team since her freshman year, grasped the ideas from the workshop as Singhania had intended: forming a connection between mathematical concepts and their application in robotics. Wong also recognizes the bigger picture behind alumni coming back after college to mentor the team.

“I think it contributes to the idea of, you learn something, and then you go and spread that back to this community,” Wong said. “I feel like the mentors [and] alumni have always been sort of this mysterious figure behind the scenes, they talk to only the most dedicated veterans and don’t really talk with us common folk. But it’s cool to see them passing on their knowledge to anyone who’s open to learn.”

As the team members are learning the mentor’s knowledge gained from working in the industry, the alumni also receive knowledge from the students. For Singhania, that knowledge was learning how to manage students.

“Being a mentor has taught me a lot about how you work effectively with people and how to be a better people manager, which is directly translatable into some of the work that I do for my job,” Singhania said. “So I find it really interesting because I can take some of the skills that I’m learning as a mentor [and] translate that into the work that I do outside of the scope.”

One of these skills Singhania has learned as a mentor — conflict resolution — comes into play in many aspects of life, both as a mentor at school and as a colleague in the workforce.

“It can be really challenging to figure out how you resolve conflicts between two students,” Singhania said. “But there are conflicts everywhere you go, especially at work between two people who have disagreements on how you build a certain thing. Two kids’ opinions on how you build the robot [and] two of the engineers’ perspectives on how you design some program is directly translatable.”

Alumni instruct MVRT on scouting strategy in preparation for competition season.

As Shinta also draws a parallel between working as a professional and as a student, he believes translating mentors’ perspectives to the team environment can be helpful in bringing real world exposure to the students.

“To have the people from the working, professional environment to come in to work with the students will give them a different perspective, not just the educational teacher’s perspective,” Shinta said. “But this is the way it is when you’re really out there working, because it’s a different environment.”

However, when certain aspects of the team are controlled by mentors, the environment changes to one that Shinta views as possibly detrimental to student growth. While Shinta admires other mentor driven teams — such as Bellarmine Robotics Team — that have their mentors set policies and sometimes, even the robot’s design, he believes that this isn’t out of the spirit of FRC.

“[FRC founder Dean Kamen] said he wanted to have students seeing engineers do amazing things, in other words, to inspire them,” Shinta said. “But that’s not going to work at Monta Vista, students aren’t going to want to watch anybody, they want to do. They’re smart enough and talented enough that they can do those things. And they don’t need that much assistance.”

In spite of Kamen’s advice, Shinta prefers the team to build the robot without his interference. Instead, he supports the team by providing assistance with tools and machines to avoid taking away from the student’s learning experience.

“Our students — they already want to be engineers,” Shinta said. “They just want to have a good experience, of something that’s fun, [and] I think they do learn a lot of stuff in robotics. I’m not saying the other teams don’t learn, they do learn from experts, but there’s a lot of a difference in how you learn when you’re doing it yourself and when somebody else is doing it for you. And I feel the richer experience is actually doing it yourself.”