Life after death

September 17, 2018

Death. A process that occurs every day but isn’t talked about often because it represents something unknown. However, there are a number of people who believe in an afterlife, potentially changing their perspective about losing their life because their soul continues to another place.

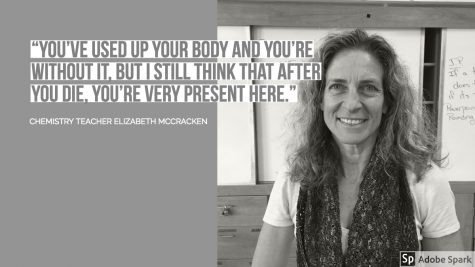

Chemistry teacher Elizabeth McCracken not only believes that an afterlife exists but also that leaving this world after death is advantageous for an individual.

“I think it’s positive,” McCracken said. “I think that as we continue to evolve, it can only get better. So, wherever you are when you start in your life, by the time you leave your body, you’ve learned certain things. Whatever comes after that will just be better [because] you’ve learned.”

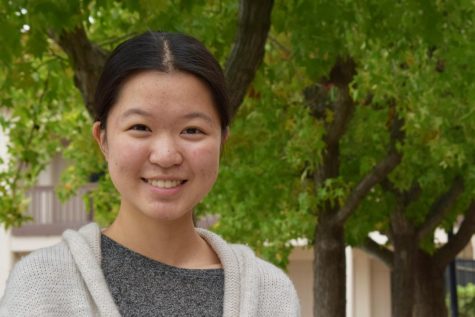

Belief in an afterlife can be comforting, especially for young children who are curious about the concept of death and what comes after it. Junior Ashley Yeh believes that introducing a positive belief to children who are curious about the subject can help alleviate their fear of death. She would tell them there is a “better place” ahead that they will love and where they will also find their happiness. Although Yeh wants to give that comfort to children, she also believes that it’s important to give them their freedom to explore on their own.

“I don’t want to impose my beliefs on the child,” Yeh said. “The child has the right to make their own beliefs. They have the right to choose whatever they want to believe. I’m not going to tell them they go to heaven or hell because they don’t need to believe that.”

Like Yeh, English teacher Clarke is also open toward different perspectives of the afterlife.

“I mean, so many different religions have different [sorts] of world views and different conceptions of the cosmos,” Clarke said. “And they’re all conflicting or nearly all conflicting with each other. I don’t have any problem with any one of those, as long as it fundamentally prioritizes the kind of values which I sort of respect in this world.”

In fact, Clarke doesn’t find the thought of the afterlife interesting at all. Rather, it’s the life here on Earth that matters to him: more specifically, he wonders how belief in a so-called “afterlife” determine one’s actions in their present lives.

If one is a Christian, for example, Clarke notes that the adoption of values such as charity, good works and humility as preparation for heaven are perfectly fine.

“[However], if your version of Christianity is something that leads you to go to foreign countries and try to convert people and kill them if they won’t convert like [in] the Crusades, well, okay, that’s not a good thing, right?” Clarke said.

Clarke himself, however, is not religious. He considers himself agnostic. An atheist does not believe in the existence of a God, but Clarke has neither faith nor disbelief in God or an afterlife. Like Clarke, Yeh isn’t necessarily devoted to any religion, but she still believes in an afterlife.

“Basically, heaven is for good people and hell is for bad people,” Yeh said. “But, normal people, like [if] you can’t really decide if they’re strongly in heaven or hell, they kind of go into limbo. It’s basically like a waiting room for when you die and [for you] to wait there in perpetual mediumness until you get upgraded to heaven for doing something.”

Similar to Yeh, English teacher Shozo Shimazaki and Social Science teacher Pete Pelkey have also mused over some personal conceptions of the afterlife. Perhaps, Shimazaki describes, it’s one room where one can only watch a video of their entire lives over and over again — every single second. The “movie” might be complete heaven or downright hell, all depending on how one lived their life. Technically, one would “relive” their lives for eternity.

Pelkey admits he is unsure of the specifics of an afterlife but certainly expects some sort of reckoning.

“I don’t know if you go to heaven and God says, ‘Nuh, uh you’re not good enough. Off to hell with you,’” Pelkey said. “I don’t know if it happens like that. But there’s got to be … some kind of internal [conflict] too.”

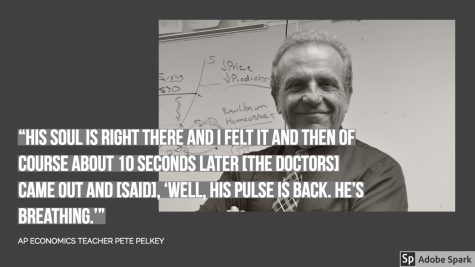

In fact, as an ex-paramedic, Pelkey believes he can tell the difference between humans with or without a soul, especially after seeing hundreds of patients who were close to or at death’s doorstep.

“I’ve watched a lot of people die,” Pelkey said. “You can watch people go from human beings to inanimate objects and you watch them do this. You see the soul disappear.”

Personally, he recalls his nephew who lay in El Camino Hospital after a failed suicide attempt, without a breath.

“He’s coming back,” Pelkey said. “I don’t know if he’s going to stay [but] he’s coming back because his soul is still intact. His soul is right there and I felt it and then of course about 10 seconds later [the doctors] came out and [said], ‘Well, his pulse is back. He’s breathing.’”

His nephew died 10 days later from complications related to the suicide attempt, but Pelkey is sure there must be some place dead souls reside. It might not be a heaven and hell described in the Bible, but he does believe in an afterlife of some sort. He is also confident there is some sort of entity out there, connecting the souls of everybody together. This same belief in the afterlife is what McCracken believes alleviates the fear of leaving the present world.

“I think death is less scary than when you know that it’s just your soul changing form — that you’re not done,” McCracken said.

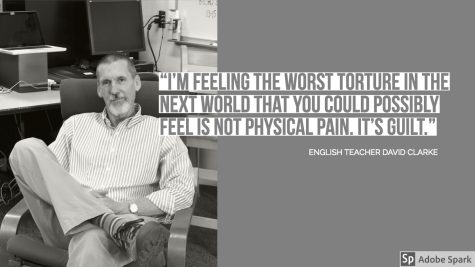

However, while it may be reassuring for some to know death isn’t the very end, Pelkey wonders how one will be judged at the end of their life. He believes it is based on whether or not one lived honorably, how one felt at the end of their life. Clarke is in complete agreement with Pelkey.

“I’m feeling the worst torture in the next world that you could possibly feel is not physical pain,” Clarke said. “It’s guilt.”

Clarke doesn’t consider himself morally perfect, but he isn’t at all scared of what’s to come. And if the supposed world ahead punishes him for failing to dedicate himself to a particular religion, rather than determining salvation based on his personality and actions, Clarke can certainly “live with” being punished for his agnostic beliefs.

However, for this potential afterlife, he does have some qualifications.

“I certainly don’t want to get in a situation where I say, for instance, that we can look the other way at pain and suffering in this world because it’s all going to be okay in the next [world] and the people who did it in this world are going to be punished in the next world,” Clarke said. “[Or that we can say] the people who are suffering in this world are going to be living happily in the next. I don’t think the [rewards] of the next world can be used as a justification for the way for the ills of this world.”

And Clarke feels that if that’s truly the case, the afterlife is a “messed-up world.”

Unlike Clarke, Yeh has particular ideas about what the afterlife — specifically, hell — could potentially feel like. Instead of hell being a place that can cause pain, Yeh believes that it’s nearly the opposite.

“Frozen in time. Like in hell, if there’s fire, there’s like heat, warmth, and fire, kind of represents, like symbolizes passion sometimes,” Yeh said. “But the way I see hell, it’s just devoid of anything. Devoid of emotion, devoid of warmth. Basically the opposite of passion.”

While Yeh believes that there are solid divisions in an afterlife, McCracken believes that an individual remains on the planet, connected with human beings, based on what the person they’re interacting with believes in.

“I think it’s the same [but] it’s more like you change your form so you’re not in the same body that you were [as a human],” McCracken says. “You’ve used up your body and you’re without it, but I still think that after you die, you’re very present here.”

“I think it’s the same [but] it’s more like you change your form so you’re not in the same body that you were [as a human],” McCracken says. “You’ve used up your body and you’re without it, but I still think that after you die, you’re very present here.”

Shimazaki also brings up the integration of both the deceased and living. He believes those who pass away “live” within those who are still alive, similar to how McCracken believes those in the afterlife can choose the living person they really want to interact with.

“I think that after you die you are definitely accessible,” McCracken said, “But I think that people have to be open to knowing that.”

So, according to McCracken, while one’s present life really does matter, it ultimately fades in comparison to what’s waiting for them beyond the grave.

“Everything else we do in life, right, it’s we could almost call it busy work compared to these questions you ask,” Shimazaki said. “They keep us occupied. But these are, to me, the real questions.”