As the cable car glided along it’s path in the air, she couldn’t help but shed tears in response to the gut-wrenching terror. Every single time one of her family members shifted slightly in their seats, peering over the edge to catch a glimpse of the green forest below, without fault she could feel the cart shudder in response, sending adrenaline pulsing from her head to her toes. The feeling worsened when the suspended cart switched cables mid-air, causing her to shake from side to side.

Her overflowing, salty tears didn’t come to an end until the ride was over, seven kilometers after their initial boarding.

Junior Mahima Kumar was in fifth grade when her family went on the gondola ride while on a vacation in Australia. Her fear of heights, more specifically the fear of falling, worsened.

Nowadays, as a high schooler whose legs are a little longer, hands a little tougher and mind a little stronger, heights and falling intimidate her on a smaller scale. However, her fears from days as a child had evolved, transformed with time, some leaving her mind, others laying low in the depths of her stomach, a few completely new to her body.

“As you grow up, you learn more about the world, and you learn more about other people’s perspectives and other people’s stories,” Kumar said. “You realize that there is a lot more to your fear than what it was when you were eight years old.”

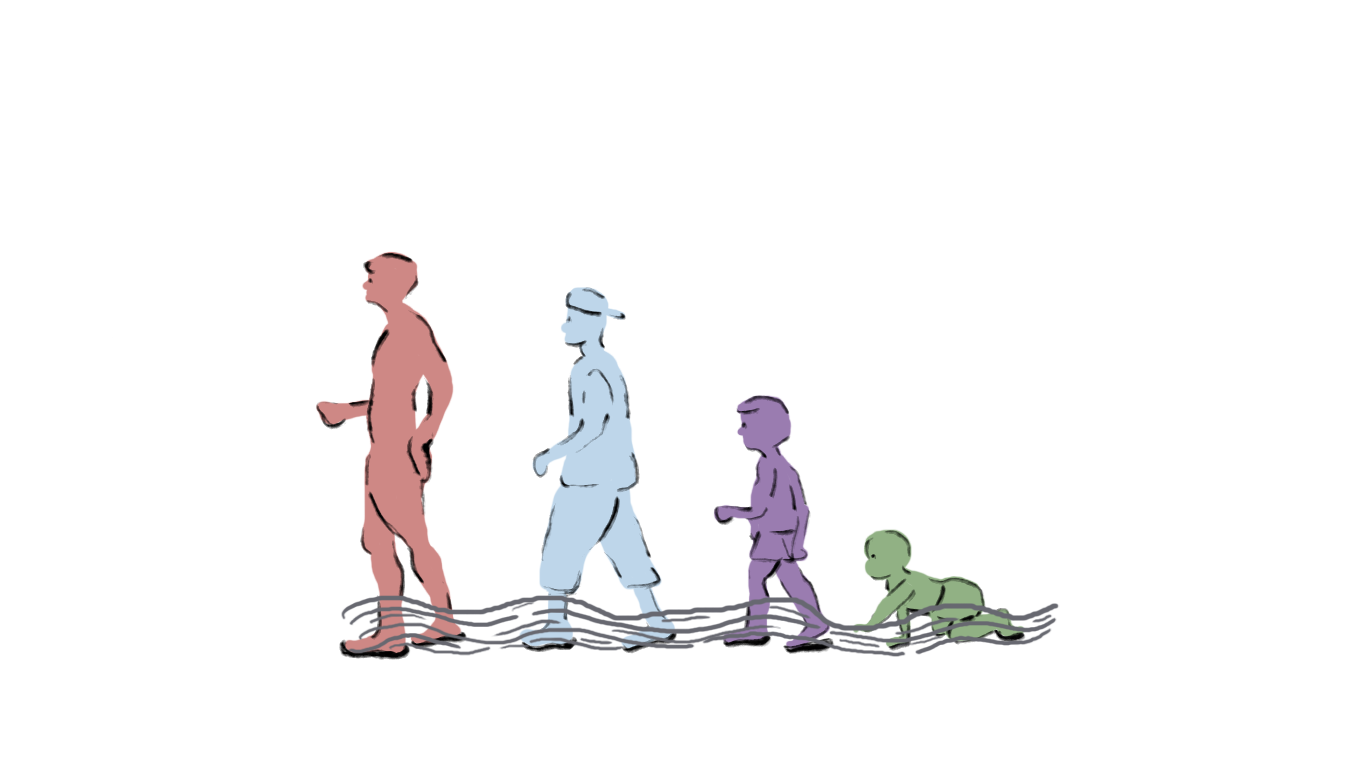

Age does more than simply transform your baby fat into muscle or once hairless arms into bushy jungles, it furthers your thinking, matures your mind and adds depth to your fears. From clowns to the unknown, from running around the playground while being chased by your friends to running around the house after your screaming children, people at different stages of life are terrified of different things.

English teacher Vanessa Otto know this process best, as she’s experienced fear transform from one stage of life to the next.

As a child in third grade, Otto was scared of Chucky.

The concept of a doll with piercing blue eyes, red hair and jean overalls paired with the scars across the face and a maniacal laugh coming to life and killing people terrified her. Otto’s fear sprouted from the trailers of the movie which played on T.V. in 1998, but she never watched any of the “Chucky” films until senior year of high school with her friends after prom. As a third grader, she would hide behind the couch to avoid looking at the doll, but by the end of her high school career, she laughed at what she later decided was poor cinematography.

Years later, she went to Universal Studios in 2008 where she entered House of Horrors and coincidentally, there was a room full of Chucky dolls.

“I was an adult by then, but it was terrifying,” Otto said. “And then, to make matters worse, out of nowhere, one of the Chucky dolls comes to life and starts chasing me around with a fake knife.”

In middle school, Otto’s fears expanded, grew in maturity as Chucky no longer remained her main source of terror, but rather the issue of identity became a source of anxiety. There had been pressure to succeed yet at the same time, there was pressure to be popular among peers.

“You didn’t want to have that label as being a ‘nerd,’ which is kind of different, I suppose, nowadays and maybe specifically at Monta Vista,” Otto said. “But I distinctly remember wanting to excel academically but not wanting to have that label of ‘nerd’ placed upon me.”

While Otto worried that she wouldn’t be part of the “popular” group, Kumar worried she wasn’t part of a group at all during her own middle school years. As she transitioned from elementary school to sixth grade, where unknown faces became more prevalent, she noticed her sudden fear of the social aspect of life—she worried about the people around her not truly liking her, of exclusion.

“There were a lot more insecurities and there was a lot more ‘am I be friends with these people?’ Is it possible are they going to let me in?’” Kumar said. “Eighth grade was the year when none of [those feelings] actually mattered, it was just me being in my own head, and I knew who my friends were.”

Soon after, high school brought upon Kumar a whole new revolution of fear: now it’s all about the future.

Kumar is struggling with the constant fear of accidentally tearing herself down and ultimately ruining her future—a fear she thinks to be irrational because she knows well that it’s possible to make up any mistakes made in high school later on in life.

“There’s so many ways to make up for it but I think it’s just the environment we’re in is just very … pressured to do well in high school,” Kumar said. “We’re kind of taught that what we do in high school will be a direct reflection of the rest of your lives.”

This pressure is something Otto felt as well and something that spurred her fear of disappointing her parents during her own high school years.

“They’re your champions throughout life, and they give you a lot, so you want to make sure you’re worthy of all that they’ve given to you,” Otto said.

Yet while she wanted to play the role of a good daughter and live up to their high expectations, there was always a part of her yearning to venture out and explore, and fearing that she wasn’t experiencing life enough. She describes that her parents had what they called a “fun limit,” restricting her from doing too many things on the weekend. She feared that she would miss out on the parties, field trips and other life experiences her friends seemed to be having. Even now, she fears that she didn’t rebel enough as a child. That she was a little too compliant and if she had been a little more of the classic “teenage rebel,” she might have had more of the experiences her friends had growing up.

Now as a parent herself she’s beginning to understand the overprotective actions of her parents. As the mother of seven-year-old twin daughters, she fears placing too many rules and expectations on them and then failing to set a good example—practicing what she preaches.

“It’s very easy to give a bunch of rules, right?” Otto said. “Not so easy to live by them and serve as an example.”

However, the fears Otto has now are fears that were once non-existent in her life. A child, like second grader Arjun Joshi, doesn’t think about leaving a positive imprint on this world or the regrets that accumulate over time.

After completing his own fears and the fears of those around him, he came to a quick conclusion:

Adults were afraid of everything, but specifically his adult father was afraid of breaking the fan, or getting robbed. He also believed adults were afraid of tornados, unless they had basements because then they could hide there.

He too is ultimately afraid of getting robbed and tornados. And of lion cubs attacking him. And of getting in trouble whether it be by mom or his teachers at school. But he is not, he boasts, scared of jumping down from a very tall pole at his school, while his friends are. While they look at the pole in fear, he can jump off the pole from high up, from as high as the height of his house (the imagination of a child is a beautiful thing).

“I jumped off into the tanbark,” Joshi said. “And then I landed on my butt.”

Did that hurt?

“No.”

Really?

“A little bit.”

A little bit. Facing or dealing with a fear, whether it be jumping from a tall pole or walking into a room full of Chucky dolls, might always hurt, at least just a little bit. And as an adult, it can become even more of a challenge with growing responsibilities, such as becoming a parent. But Otto feels that dealing with fears can actually become easier as one gets older, as she has learned new coping mechanisms along the way.

“I feel like as a child, as a young adult, as a high school student, as a college student, you’re more concerned with goals that are more immediate, fears that are more immediate,” Otto said. “But then as an adult, it’s beyond that … There’s a greater world around you, you’re a member of the global community … there’s a lot of pressure I think that comes along with that, but your ability to cope with those types of pressures become easier as you get older.”