Story by Jessica Xing and Jackie Way

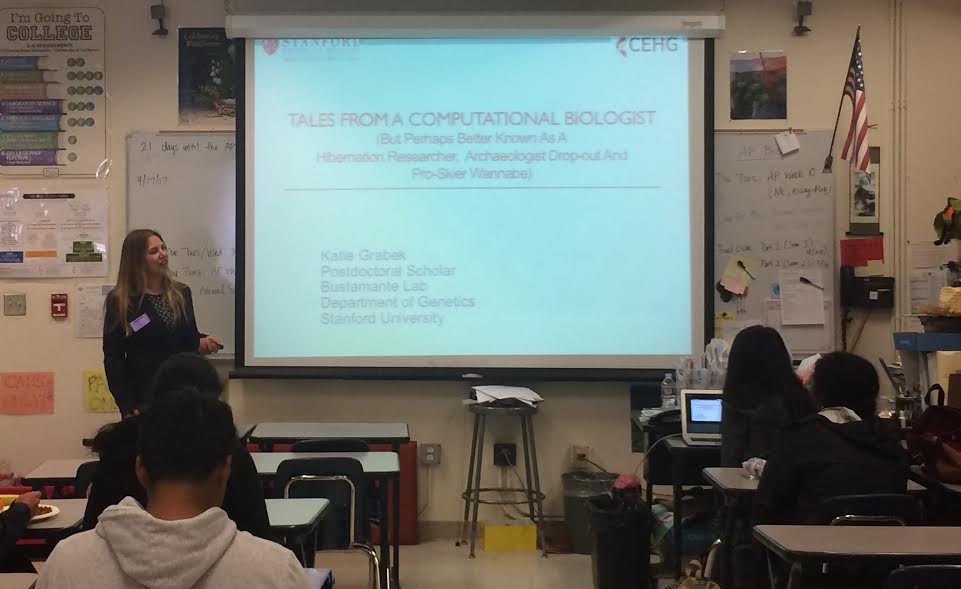

On April 17, Stanford postdoctoral researcher Katharine Grabek spoke about how she became interested in computational biology and how it applies to her current work focus: analyzing the hibernation cycles of squirrels by looking at their genetics. To the room full of SNHS members, she started out by discussing how she wasn’t interested in science at all at first: in fact, when she started high school, she wanted to be an archaeologist and a professional skier.

EE: So why computational biology? How did you first get into it?

KG: The methods we started using and adopted were a lot more complicated and high dimensional. We started looking at one gene, then we started looking at thousands of genes. At first we were working with a bioinformaticist and she was doing all the data analysis, but she was doing other projects too so we’d had to wait two weeks to get something, and it started getting annoying. My first desire was to just change the color on a graph and so that’s when I started learning more about the methods and I said ‘Oh, I can do this’ so that’s how I got into it.

EE: How have improvements in technology changed the field of genetics overtime?

KG: Sequencing costs have come down. When you think back in 2000 about how the first genome was sequenced, it was millions of dollars. Now we are getting down to a thousand dollars a genome and even less. The technology for sequencing just keeps getting cheaper and cheaper so we are able to do more and more. What we are getting now is more and more data — before you only got a handful of data so you had to do what you could with it, and now the order of magnitude of data collection just keeps increasing.

EE: What is the most interesting experience you’ve had since starting your postdoctoral research?

KG: One of my Ph.D works, I came up with an unexpected result, and one of my thesis committee members said that I shouldn’t even be seeing this. So either the experiment was wrong or there was something completely different going on with the squirrels going on than I thought. As it turns out, I didn’t design the experiment wrong. It was something different going on. That was really interesting as it kept me up a lot of nights wondering what it meant, and how it fit into the bigger picture.

EE: You stated in your presentation that what first got you interested in science in college was seeing all the unknowns there were. What about the unknowns in science intrigue you?

KG: I think that’s just my personality — even when I was a kid I always had a lot of questions. I used to think of a lot of ‘what if’ scenarios, and used to stare off a lot, so my mom had to go like ‘Earth to Kate’ a lot of the time. I wanted to be an archaeologist at first because I wanted to make discoveries. The most rewarding experience is making new discoveries, like you are the first one to ever see this new thing, that’s the best feeling. It’s like you are an explorer back in the day when the world was still new and you want to know what it means and what do you know. You feel like you are making a contribution to the world.

EE: What advice would you have for future students going into scientific research?

KG: I think if they are looking to go into academic research, they are going to be in it for the long haul. There’s never going to be a point where you’ll be done learning. No, you’ll always be learning, and if you love learning and you are curious about the world then it’s great because that’s what research will be like for you. You are living for that moment you finally get that discovery. You have plenty of time though because as a high school student you have so many career paths — you just follow what you are passionate about and it’ll work out for you.