remont High School senior Ana Maria Vazquez had always pronounced her name with a lilt that highlighted her Latina descent. And on the first day of her freshman year at FHS, she said her name in that same manner when the teacher took attendance. Her teacher began asking her about where she was from: whether she was from Spain, whether she knew who her father was, whether her father was a construction worker. She wasn’t sure if he was simply curious but it didn’t matter, the questions about her family and whether she was born in the U.S. still made her uncomfortable.

It’d never drawn any attention when she attended Columbia Middle School, a school that had a large amount of students of Latino descent. But immediately after the teacher’s questions that day, Ana Maria stopped pronouncing her name with the familiar cultural intonation. She dropped the second half, Maria, altogether. If she accidentally introduced herself as Ana Maria, she would get mad at herself. Her teachers and friends now know her as Ana.

“As soon as I said that I’m Mexican, it felt like my teachers lowered their standards for me and so I changed the way I pronounced my name to sound like ‘Ana,’” Vazquez said. “I cut off the ‘Maria’ because I didn’t want teachers to treat me differently.”

Throughout the year, she recalls that the teacher would offer to give her a calculator if she couldn’t afford one. He exempted her from group projects and told her she only had to do every other problem on homework assignments. But Vazquez had grown up taking advanced classes and she knew that she didn’t want this treatment simply because of her name.

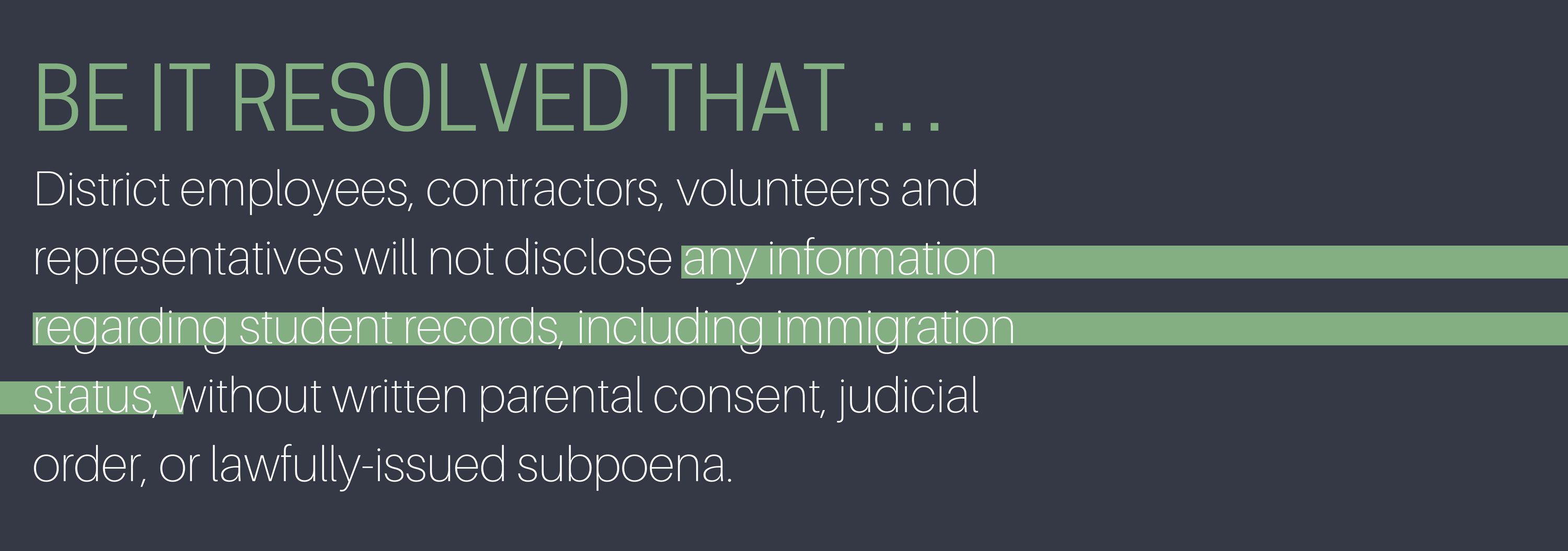

Vazquez is among the many individuals who played a part in the adoption of a new FUHSD resolution. On Feb. 7, FUHSD passed Resolution #1617-12 at their board meeting, establishing that district employees will not reveal a student’s documentation to outside officials unless obliged to by law. FUHSD Student Board member and Cupertino High School senior Sanika Mahajan helped by reading over the FUHSD’s letter, getting signatures for the petition and speaking about the resolution in her student report to the school board. But during their conversations, Mahajan sometimes found herself in shock when she discovered how unsafe some students felt at school and she unquestioningly responds that it is both FUHSD teachers and students like Vazquez that pulled the resolution together.

With the political climate growing tense over Trump’s executive orders limiting immigration, Vazquez couldn’t help but feel fear at times. Even though she isn’t undocumented, she realized she still wasn’t the only one feeling the fear.

“The fear I felt was not only manifested in my mind but in all the hallways that undocumented students walk through,” Vazquez said. “The fear comes from the uncertainty of not knowing if when we get home, our families will be there or not or even [if] we’ll make it home because deportation has the power to deviate the entire course of our lives.”

Mahajan and Vazquez both know the school district is diverse— not just in terms of ethnicity, but also in terms of sexuality and race. To them, that’s where the resolution offers hope. It runs far deeper than protecting undocumented students in the district.

Vazquez noted that the board meeting placed an emphasis on making it clear that the district’s purpose is simply to provide a place for youth to receive an education, to give them an educated voice. Mahajan echoes that sentiment. The resolution is merely a step towards a school district that truly accepts the diversity of its students in all aspects.

At the board meeting, Mahajan watched the board members around her submit their votes. She also had submitted a vote too, which was recorded as an advisory note that wasn’t part of the overall vote. And when the resolution was adopted unanimously, Mahajan looked out and saw Vazquez in the crowd, smiling. Without words, that smile reminded Mahajan of all the reasons that the resolution was important. The weekly meetings on Tuesdays that had been taking place since November to discuss the goals of the resolution, the conversations between Vazquez and Mahajan had culminated in this moment.

“When they adopted the resolution and the policy, she was smiling and I saw that and I just felt like a moment of sort of closure for her and that made me more happy than anything,” Mahajan said.

Vazquez recalled the strength it took for her to fight back the tears of happiness that brimmed in her eyes as she watched the board adopt a resolution that represented so much for her. She’d always looked up to the civil rights leaders who had fought to give education to all. To let the marginalization of students continue only seemed to dishonor everything those leaders had fought for. And in her own way, Vazquez contributed to this resolution and just like those leaders before her, fought to preserve one of the most basic rights of education.

“It felt amazing to know that the district cares about all of the students, not just the documented students and the citizens,” Vazquez said. “Now I knew that the FUHSD doesn’t stand just for the majority, but for also equal opportunity and inclusion… it just felt amazing to know that they were there and they were going to fight for all of the students.”

According to Vazquez, the concept of educating teachers to prevent accidental insensitivity towards a culture or ethnicity floated around during recent board meetings so that no one will feel uncomfortable in the same way Vazquez did that first day of her freshman year.

Vazquez also hopes to talk to other schools within the district about the resolution and more. To both Vazquez and Mahajan, the resolution’s importance lies in not just the words themselves but the welcoming message it conveys. Mahajan agrees that this resolution is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to communicating the board’s accepting stance.

“It’s not just about passing the resolution,” Mahajan said. “It’s just about how the board communicates that to the community… that all students, regardless of what their… documentation or lack of documentation may or may not be, have a right to show a face in the district and get an education without a fear of going to school.”

The resolution has only been in effect for a less than a month, yet Vazquez can sense a shared feeling of relief ripple through the student population.

“From talking to students, there are a lot of students that do feel alleviated because now they know they can come to school and know they’ll be safe and the district’s not going to give away their information and jeopardize their stay in this country,” Vazquez said.

To Vazquez and others, the resolution offers comfort, enforcing that the idea that the district has a student’s best interests at heart regardless of whether they are documented or not.