wo years ago, I joined the Facebook group “You know you are from Cupertino if you remember…” With about 10,000 members, the group engages in daily discussion about memories and places in Cupertino. But even after living in Cupertino for the last 16 years, I scroll through the page seeing names I do not recognize:

The Surf Shop. Aloha Boats. Sunshine Supermarket. Winchell’s Donuts. Bob’s Big Boy.

These places are foreign to me.

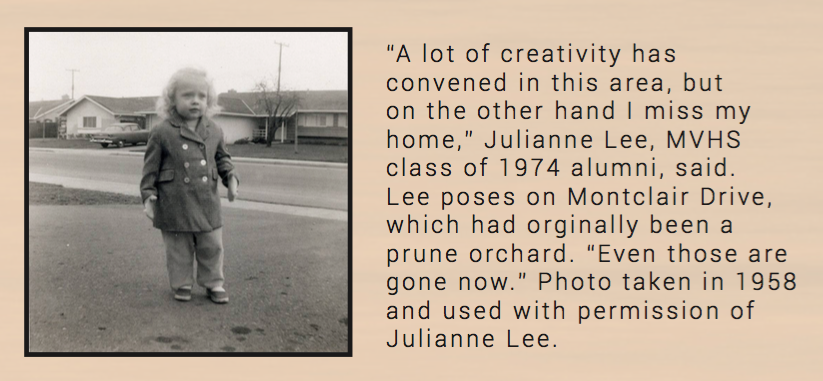

MVHS class of 1974 alumni Julianne Lee recalls a different Cupertino than the one I know. When she was a young girl, she remembers getting in trouble for playing cowboy in the orchards that stretched for two-and-a-half acres. In the spring, Lee would hide among the three-foot-tall mustard plants, smelling the air around her. This scene, to her, was idyllic.

“I remember I would just lie in the ground where nobody could see me,” Lee said. “It was incredible – the peace. That’s right about when property value skyrocketed, and things changed.”

This Cupertino is foreign to me.

The Cupertino Lee talks about — the one with orchards and horse stables — is a distant place lost under the mask of the Cupertino I live in — the one that’s home to Apple’s headquarters and new downtown. Development has inarguably changed the landscape of Cupertino.

This November election posed the question of this development to the citizens with Proposition C — an initiative to slow development — and Proposition D — an initiative to revitalize Vallco Mall into The Hills. The community voted “No” on both.

These results seem to display a dissatisfaction with modernization and an influx of people. As Cupertino takes strides with its new developments, there is a simmering sense of abandonment of Cupertino’s history.

This modernization is not something unique to Cupertino, but the speed of this change is disorientating for some.

Just in my four years of high school alone, Cupertino has built a Main Street, evicted small business stores in Vallco and added hundreds of apartments.

Change, in Cupertino, happens fast. Whether good or bad, it’s time we slow down to ask “why?”

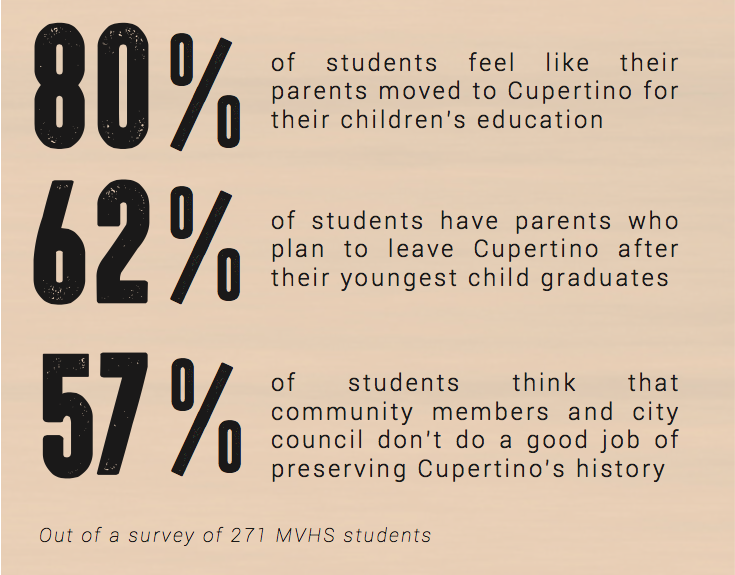

My parents moved here for the same reason many of my peers landed here: education. And next year, when my parents will say their goodbyes and send me off to college, I know they will also be bidding our expensive house goodbye. My situation is not unique. In a survey of 271 MVHS students, 80 percent felt their parents moved here for their children’s education, and 62 said their parents plan to leave once their youngest child graduates.

My parents moved here for the same reason many of my peers landed here: education. And next year, when my parents will say their goodbyes and send me off to college, I know they will also be bidding our expensive house goodbye. My situation is not unique. In a survey of 271 MVHS students, 80 percent felt their parents moved here for their children’s education, and 62 said their parents plan to leave once their youngest child graduates.

With high housing prices, Cupertino acts as a temporary home for many.

Teachers work in Cupertino until they decide to buy and house and can’t afford anything within a reasonable commute. Small businesses clutch onto their property until taxes become unbearable. Parents pay the high property taxes until their youngest child graduates and they depart from their houses.

Cupertino is constantly changing. Every 10 years community members are filtered out as they search for a more affordable housing.

When Cupertino acts as a temporary home, the community question can often shift from “how can I preserve this city’s history?” to “how can I shape this city to be profitable for myself?”

Adding more chain businesses, revitalizing Vallco and constructing a downtown adds tangible economic value to the property in Cupertino at the cost of tearing down less profitable small businesses and other landmark locations full of memories.

Cupertino resident Susan Pimlott’s first job was making falafels at Vivi’s in the 70s. About two months ago, the place, to her despair, was torn down.

“Vivi’s was a special place,” she said. “A lot of the early ideas [that led to products like the iPhone] were hatched over falafels.”

Much of the attraction behind the Cupertino Facebook group has to do with nostalgia: “day of old Cupertino and the Landmark buildings are gone,” “sad to visit Cupertino anymore,” “a real Cupertino tradition gone with the wind.” This page, as one of its members pointed out, “is often an obituary for things we enjoyed back in the day.”

“It’s just part of human nature: Change is hard,” Pimlott said.

And I can sympathize with that. I would be devastated to come back to a Cupertino where the place I had my first kiss — Three Oaks Park — was replaced with another set of apartment buildings or our family’s go-to restaurant — Cicero’s pizza — was replaced with another Pizza Hut.

As Lee put it, “change is coming in and homogenizing everything.”

With each development, with each passing year, Cupertino assimilates to a more generic city. A city with more corporate places and fewer family-owned businesses. A city with more apartment buildings and fewer community gathering spaces.

Change is not the enemy. Homogeneity is.

Twenty years down the line, if I join a Facebook group, “You know you are from Cupertino if you remember…,” I fear the only name I’ll see is “Starbucks.”