She was there when the war began.

It was on a night 10 years before that they stole everything she held dear and beloved as she watched atop a ledge in the cold, cold night, a small, scared child wrapped in the winds, and sobbing, wishing the old stories of the kings and queens who were kind and just were true — but she knew they weren’t. Aecor had already fallen to the Indigo Kingdom, and she, Princess Wilhelmina Korte, was an orphan. In one night they had taken everything away.

She was there when the war began. And when it ended.

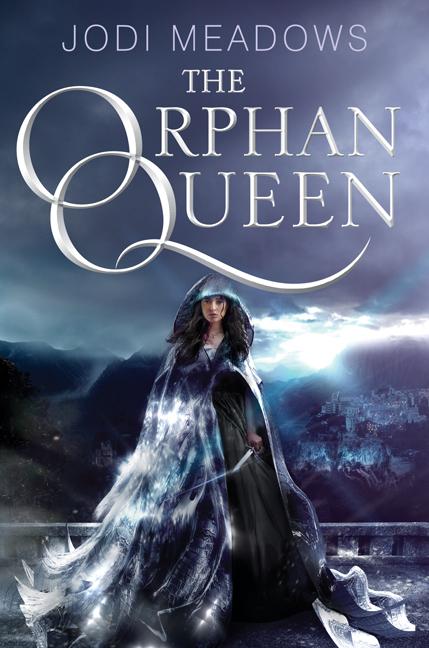

Despite sparse worldbuilding and a few plot holes, “The Orphan Queen” is a light, entertaining read with a creative world and magic system: the story of a thief, a spy, a vigilante, a princess, the story of a girl who wears a hundred lives and faces.

Wilhelmina and her band of displaced young nobility, the Ospreys, plot to reclaim their kingdom Aecor and halt the creeping, seeping ethereal wraith, fog born of magic which pours into vales and forests and threatens to claim all lands. Now in the city of Skyvale, Wilhelmina infiltrates the Indigo Kingdom’s palace disguised as a duchess and disperses wraith monsters by night with Black Knife, a vigilante she encounters while partaking in petty street crime. It is here, in the dark openness, that fragile trust and love unfurl. And it is here that Wilhelmina discovers the destructive power of lies spun from hatred, shame, fear, duty — and, most devastatingly, kindness.

Meadows’ world is dreamy. In a city built from mirrors, the people nestle in coat pockets and behind cotton shirts little round mirrors, protection charms, holding them close, praying the encroaching wraith will never come. It is in such imaginative settings and faint brushes of culture, few and far in between, that the touches of ambition and what could have been are so apparent. Sadly, Meadows fails to fill in her vague, nebulous world.

Perhaps by the very nature of a world in which magic is forbidden, the ideas which set apart “The Orphan Queen” as original amidst worlds made from patches of this or that story — the wraith pollution and animation of objects — are neither developed nor explored to their full potential. Wilhelmina uses her magic sparingly. This, in and of itself, allows little opportunity to understand how she animates, why she is a magician when others are not and where the bounds lie of what she and other magic holders can do — and should do.

The promised trickery and richly-layered “hundred” identities, beneath luscious raven lashes and pretty little satin dresses, blushing girls, courting boys and midnight masks of sable silk, are lost in predictability and lack of profundity. The characters and identities they don as coats may be fairly — yet not finely — nuanced.

In the beginning they are nothing more than worn-out tropes, the dauntless young heroine and the righteous vigilante boy, yet as the story grows and matures, they are more subtly drawn into something of their own, pieced together from their hundred identities. As Wilhelmina ventures into Skyvale and the Wraithlands, the fallen lands beneath the weeping night and unheeding stars, the unbridled fury and pain she has harbored for so long, dark within, unfurl. And she hesitantly, tenderly, passionately falls in love with a city, a people, a kingdom, with the woeful contradictions that make them human — and at last — who she is.

Yet however flawed or likeable, the characters are not painted so beautifully and creatively that they are gorgeous, lustrous, or simply different enough from the omnipresent tropes of high fantasy. And Black Knife’s identity is rather obvious, though this does not diminish the sweetness of his and Wilhelmina’s love, their story by night of the nameless girl and the faceless boy with the mask. Their story of a delicate, exquisite, gentle and unreal love, for each had fallen in love with the other’s lie.

Wilhelmina is poorly learned in the art of espionage. She foolishly and naively relies upon a flirtatious demeanor and pretense of innocence to tease out the truths she seeks. Sadly, it is a wonder that she is not discovered much earlier while sipping fine wine and glancing at courtiers beneath blackened lashes in her frilly court foppery and poorly-researched disguise, although her light-hearted banter and the shallowness she feigns are certainly fresh and funny as she navigates the bejeweled life at court.

Yet the infiltration of the palace is far too simplistic, with the Indigo King and Prince too willing to shower with trust, riches and palace rooms strangers who claim to have fled the wraith that befell them. At times, issues resolve with too much ease, as improbabilities which may strain credulity.

“The Orphan Queen,” albeit not quite as detailed nor lush and original, is beautiful in its own way, with a creative world of tall, stark white monsters and what it means to hold — and be, at least in small part — a hundred identities. Though flawed, though never quite enough to outlive the tired tropes it bejewels and embellishes, “The Orphan Queen” is still a lovely, if only entertaining, read. Worth a try.

Verdict: Borrow it.