“[The towel] is pink in color and square… As I grew up, I started using it, and then I obviously started getting older and bigger, so we just kept it in one of the cupboards. Then when my sister was born, we used the same thing for her,” senior Rhea Solomon said. “So my mom decided to keep it.”

Rhea’s first towel holds a special place in her heart. Worn with time and use, the threads are now coming off of the 17-year-old fabric. Yet that towel still evokes memories of her childhood, and so it still sits in Rhea’s house, folded nicely atop a cupboard shelf. The towel, with Rhea’s name sewed on in ancient black thread, is no longer used. But it is still cherished and kept.

“[The towel] was a gift given by my sister when Rhea was born,” Rhea’s mother Sujatha Solomon said. “We still have it, and everytime I see it I remember [Rhea] as a baby. It’s my sister’s gift to her.”

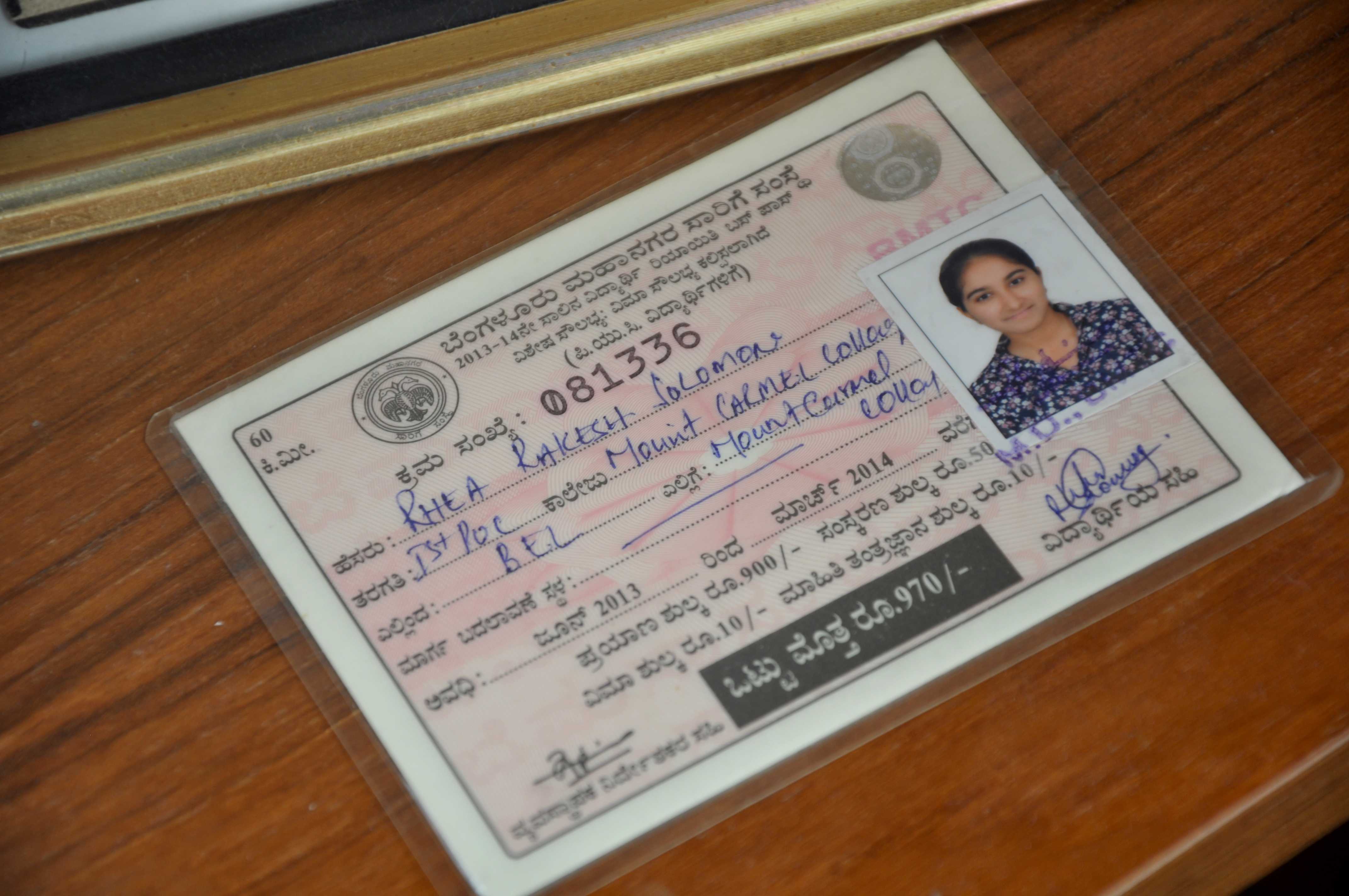

Two plastic ID cards are kept for a similar purpose. They are just like any other school identification cards, but they are issued from Presidency School and Mount Carmel College, one for tenth grade, the other for eleventh. Rhea keeps these cards, along with a government-issued bus pass, because the schools have played a major part in her life.

Rhea moved to Cupertino this past June from Bangalore, a city in India, and brought along the cards which represent her school years in India. These cards remind Rhea of the life she had before moving to Cupertino for her senior year.

Rhea keeps her ID card with her other personal memorabilia in a designated drawer.

“I keep clothes in there too, so I access the drawer everyday,” Rhea said. “That way, I won’t lose it. When I miss my friends I just look at [my ID card] and think, ‘Oh, okay. We had a good time then.’”

It’ll be safe there

As a result of having to move, Rhea and her family faced decisions regarding what to do with their possessions. They gave their electronic appliances — their fridge, oven and toaster — to Rhea’s grandmother, who moved into a different house at roughly the same time. They threw away clothes that were too old and faded to be worn. They sold furniture that held no special meaning to them. They donated more clothes to orphanages. Their friends, family and acquaintances alike even, by word of mouth, passed on news that the Solomon’s were moving and looking to give away certain household appliances. Thus Rhea’s family was able to dispose of the items they could not keep.

But due to weight restrictions on airplane flights, they still could not bring many things.

Along with clothes, collages, books and shoes, many of the family’s more precious, meaningful belongings ended up in a terrace-level room at Rhea’s aunt’s house. Among the many boxes of Rhea’s belongings stored in her aunt’s house is one with an art easel Rhea received from her father for her 15th birthday.

At two kilograms, the five-and-a-half feet tall art easel was too heavy to bring to the United States in addition to Rhea’s clothes. Rhea remembers the night she received this present: after the cutting of chocolate truffle cake in her dining room, Rhea opened an unexpected, rather heavy box to discover a wooden easel inside. Her father helped her set up the easel, and at the suggestion of her father, she immediately drew an underwater scene with a scuba diver, a shark and treasure box.

Rhea parted with her easel reluctantly.

“Since I was so attached to [the easel], I didn’t want to let go, but I had to,” Rhea said. “But I knew that it would be safe, so I was kind of reassured. [Still,] the fact that I don’t have it [with me] — it feels really bad.”

According to Sujatha, the art easel was one of the things that the family did not want to carry on the flight, but could not bear parting with. They packed such possessions carefully, so as to prevent any damage by termites, and kept it in the houses of brothers and sisters. Whenever Rhea’s family visits their native country, those objects will be there for them.

Seventy years of music left behind

Aside from her art easel, Rhea’s guitar was carefully packed away. Her father Rakesh Solomon gave away his own guitar to a relative. Even the family heirloom, a 70 year old harmonium, was left behind.

Rakesh’s grandfather was a music composer and director for music and Indian films. He composed his music on the harmonium, which has since been passed down in the family, from Rakesh’s grandfather to Rakesh’s mother, who was the eldest daughter. Rakesh then received the treasured harmonium from his mother as the eldest son.

Rakesh and his siblings had sung and played the harmonium since childhood; the harmonium was always in the family. Even when Rakesh moved from Bombay to Bangalore, Sujatha’s hometown, he brought the harmonium with him. But Rhea’s family did not want the harmonium to get damaged or lost on the flight to the United States, so the harmonium was left with Rakesh’s sister.

“Wherever I went [the harmonium] was with me always, all my life,” Rakesh said. “It was very difficult. But I knew that it would be in safe hands because everyone [in the family] is musically-inclined and talented… We all know the value of the music instrument. And we knew that everybody would take care of it.”

“Wherever I went [the harmonium] was with me always, all my life,” Rakesh said. “It was very difficult. But I knew that it would be in safe hands because everyone [in the family] is musically-inclined and talented… We all know the value of the music instrument. And we knew that everybody would take care of it.”

Resetting the counter

Sometimes the most-loved things are not kept, simply because they are not the most practical things.

Rhea’s family faced quite a few tough decisions in choosing what possessions to bring, and which to leave more than 8,000 miles away in suitcases and storage rooms — and in some cases, farmhouses. The family’s large dog required much exercise and space, and was ultimately given away to the resident of a farmhouse.

But in general terms, Rakesh believes that his family was mentally prepared to start life once more with only the absolute basics; they understood that life moves forward. Though other residents of Cupertino may possess the exact same objects the Solomon family had to leave in India, Rakesh says that his family will eventually learn about their new environment.

“Either way, we’ll inquire with some people who have already been here before us. Or we discover — go around the [city],” Rakesh said. “It’s a good feeling, to start life. Not many of us get the chance to restart life again. The counter gets reset; that’s the interesting thing. [There’s] a lot to discover and learn and move forward.”

“Either way, we’ll inquire with some people who have already been here before us. Or we discover — go around the [city],” Rakesh said. “It’s a good feeling, to start life. Not many of us get the chance to restart life again. The counter gets reset; that’s the interesting thing. [There’s] a lot to discover and learn and move forward.”

Stored memory

Even now, Rhea believes that memory or tradition is why many people may keep and store the things that they do not need.

“[The objects] may be a family thing that’s been passed on for generations,” Rhea said. “[Maybe] there is something to do with their culture, tradition, or heritage. And maybe it’s for memory’s sake. If your friend gives you something in first grade and it really means something to you, you keep it to look back.”

Storage often conjures up images of dusty boxes, suitcases and file cabinets hidden away in a room hardly ever entered, but Rhea believes that everyone should have a personal storage space.

“I feel like everyone should have a specific place, somewhere where you can keep [things],” Rhea said. “What if you lose [something] someone gave to you with a lot of love and good intention? You’re valuing not just materials, but also emotions and feelings.”