n Sept. 29, Gov. Jerry Brown signed a law making Calif. the first state in the nation to adopt a “yes means yes” policy regarding sexual consent at all colleges and universities that accept funding from the state. According to the law, consent must be explicitly given at the onset of intimacy and may be retracted at any point. Additionally, consent may not be legally granted if one of the parties is under the influence of alcohol or drugs.The law also describes procedures for providing confidential counseling to campus sexual assault victims and mandates prevention strategies for addressing sexual assault, dating violence, domestic violence and stalking.

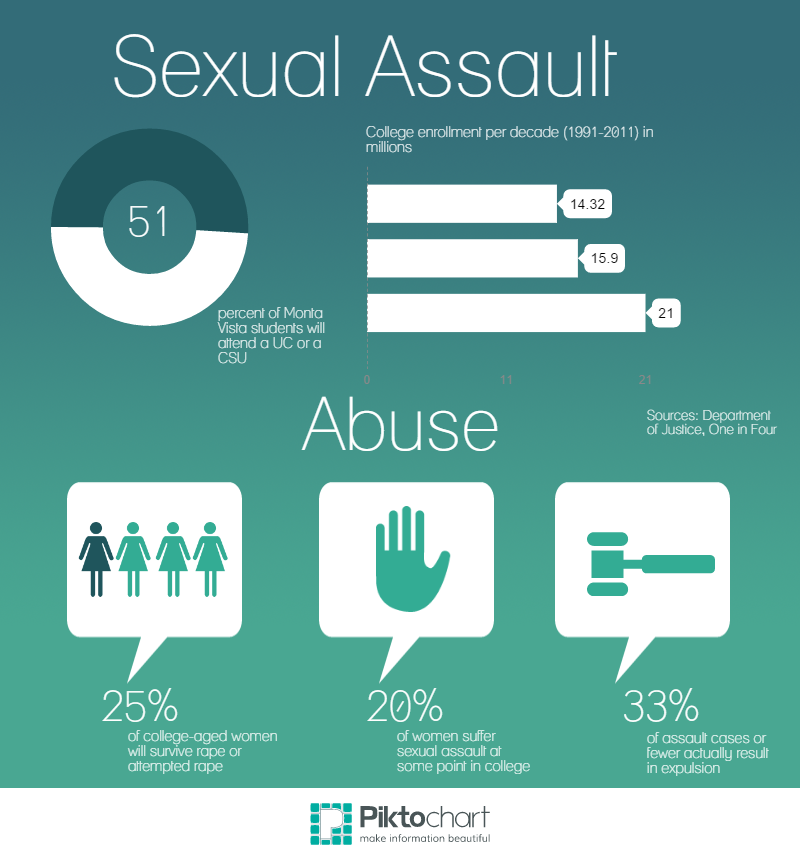

The law represents an appropriate step toward countering the wave of sexual violence present at these institutions. According to NPR, earlier this year the Department of Education said it was investigating over 55 colleges and universities — including prestigious universities like UC Berkeley — for possible violations of federal law related to sexual violence and harassment cases. The issue came to the forefront of public attention, when Columbia University student Emma Sulkowicz famously began carrying her twin-sized dorm mattress everywhere she went, and the issue has continued to make headlines with incidents of abuse occurring at schools ranging from Florida State to Dartmouth. According to the Huffington Post, less than one third of these assault cases actually result in expulsion. Sponsoring provisions to address this abuse at the state-level definitely appears in order.

The legislation signed into law by Brown does just that. It attacks the issue by addressing the crux of the problem: the ambiguity of consent. By abandoning the more ambiguous “no means no” doctrine — which implies that the absence of “no” is tantamount to consent — in favor of “yes means yes,” the law breaks the barriers sheltering abusers and defines consent in clear terms. The support system sanctioned by the law should not be ignored, as these provisions force universities to recognize the abuse present in their student bodies and take steps toward improving the situation, whether through additional counseling or proactive action against offenders.

However, we should also recognize how steep of a hill we still have to climb — one in five women suffered sexual assault at some point in college. A combination of proactivity, awareness and regulation can help reduce a truly harmful and disturbing phenomenon. One in four college aged women survive rape or attempted rape during their university experience. In addition, this auditing and regulation of state-funded universities, while revolutionary in a sense, attacks something which is notoriously difficult to monitor. Official statistics show that school reports deal only with offenses reported to college officials and are therefore notoriously unreliable, due to the underreporting surrounding rape. This difficulty of monitoring translates into difficulty of enforcing the provisions of laws, posing a serious conundrum. One step that could be taken to augment the the law would be the use of “campus climate surveys” that include questions on sexual assault, as a White House Task Force recommended. These would help colleges get closer to the root of the problem: the difficulty of accurately measuring and detecting the presence of sexual assault on campus reliably.

While the effects of the statute are restricted to Calif.-funded universities, they still will dramatically shape the post-secondary educational experience for the average MVHS student. Fifty one percent of MVHS students will attend a UC or CSU campus, all of which fall under the jurisdiction of this law. Sexual violence at these universities should decrease if the provisions of the law are effectively enforced in the coming years.