E-books are convenient, but books provide for deeper reading experience.

[dropcap1]W[/dropcap1]hen I walked into the store on a Saturday morning, the Stevens Creek Barnes and Noble was as deserted and morgue-like as every other bookstore in the country — nobody bothered to reshelve a stray Hemingway that had been abandoned among cookbooks, half the shelves were empty and there were three customers total, two of whom were dozing in the indoor cafe. Even its employees had given up long ago, and were now paid to stand and smoke outside the front door.

One woman, however, intrepidly declared that the corpse of Barnes and Noble could be revived with a single “saving grace.” From behind a 15-foot counter, placed conveniently in front of all the books, she brandished the miracle money-maker in question: a Nook e-reader. Conveniently polished and proportioned like a handheld tablet.

This new edition of the e-reader — more appropriately deemed a fatter, squarer iPad — could connect to wi-fi and access games, Netflix, iTunes and the usual internet amenities. The employee was quick to show me that yes, it could play Angry Birds, and “won’t you just look at that homescreen Facebook app!”

In answer, I asked her if the rumors were true. If print books were indeed mere relics of the past, clunky and inconvenient and on the brink of extinction.

To which she answered yes, yes and yes. [quote_right]She dragged her finger across the screen and handed the tablet to me, proclaiming that this eight-inch LED screen was, indeed, the future of all literature.[/quote_right]

I stared at the Nook for a good minute. I could certainly understand the appeal. My iPad and I were practically one, and the price of one page of a paper book is literally enough to buy a packet of 15-cent ramen. Heck, I could feed a small village with “War and Peace.”

Besides, nothing about the e-book was that much different from its archaic counterpart, I suppose: The words were still there, and even the fonts were adjustable. You could even have the text read aloud to you by a mildly creepy, pre-programmed robot-voice that turned “calzone” into “California.”

One year of purchasing e-books instead of paper ones could save you hundreds of dollars. America doesn’t need to be convinced: Amazon and Barnes and Noble claim that you can buy books in your PJs, and everybody knows that buying things in your PJs is practically the American Dream. Plus, with a handy e-reader, nobody needs to know that you’re reading Fifty Shades of Grey. In short, e-books are the younger, cleverer and thinner siblings of the nuisance paperback.

Then why did I still want to flip the counter over in a personal rendition of Godzilla? E-books, according to American consumers, lived up to the hype. They’re going to save America’s most beloved chain bookstore — a quest that has become especially frantic since the collapse of Borders three years ago. Good old-fashioned Borders hadn’t concocted a gimmicky gadget with full-color displays, and now look at what they’ve become: a liquidated franchise-corpse that has passed on from the world of the profitable.

Nowadays, people want e-books. Instant and cheap.

Still, the problem is that you can’t always trust the tastes of American consumers. Just because you like it doesn’t mean that it’s good for you. (Junk food, anyone?)

Because more importantly, I have a problem with e-readers. Not just me, but psychologists, professors and other smart people have a problem with e-readers. The main issue is the form in which these e-books arrive: These pixelated packages of text that are delivered to devices like tablets and smartphones and laptops.

All of which happen to double as gaming devices, internet explorers and social media portals. It’s an excellent business strategy. People want games and the internet, so that’s what we’ll give them, and they won’t feel so guilty because there will be a book app too. Now I can feel smart while playing Angry Birds.

Books that are accessed on devices like the Nook are dotted with millions of electronic rabbit-holes to distract us from the purity of reading a book. After all, the beauty of the book is that it is a form of perfect isolation. Instead, reading has become a test of willpower: and we can be sure that black-and-white Moby Dick isn’t faring well against the animated Fruit Ninja.[divider type=””]

Skimming the pages

According to Nicholas G. Carr, the author of The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, paperback books “force the reader to pay attention for more than ten seconds” by directing the readers’ attention to a rigid area of space. No home buttons, no apps, no texting. Only the page and its words, the physically confining area of text on paper. There are no phone alerts or touch screen games beckoning from within the book, and as a result, Carr reveals that people can read paper books much longer than they can read e-books.

In fact, a study from the University of London on e-reading has stated that readers tend to veer towards reading on their laptop and phones to “avoid reading in a traditional sense and read for briefer periods of time.” Essentially, e-books are used for guilt-free gaming and internet surfing.

With e-readers, people are instantly tempted to wile away their time “bouncing” from site to site, literally addicted to the technology-induced dopamine that floods our minds when we are jolted from point to point across the cyberspace.

Meanwhile, e-reader tablets are propelling us to become even more shallow, hyper-energetic, overstimulated-in-all-the-wrong-ways kind of people. Like all media devices, they’re shortening our attention spans and encouraging us to skim, according to The Guardian’s survey of pupils with access to all sorts of gadgets. These Kindles, Nooks and laptops have a control-F or search function that allows the reader to skip the substance and access whatever is necessary for the next day’s exam. As a result, students are no longer forced to read and absorb the material with as much depth as before.

According to a study conducted by the University of Nebraska, middle school students have already learned to cheat the system. After being assigned a novel and a corresponding vocabulary list, a majority of seventh graders located the words on a PDF file of the book instead of learning the vocabulary through context.

The same study noted that PDF and online versions of the dictionary are also detrimental to learning. When physically searching for a word in a paper dictionary, you subconsciously absorb dozens of other words by nature of rifling through hundreds of pages and thousands of words. Using a physical dictionary also allows children to learn the alphabet more quickly and remember the definition, pronunciation and etymology of words for a longer period of time.

Even worse, the new generation of tots are already learning slower when exposed to e-books at an early age — parents interact through the device instead of teaching their children how to read in a direct hands-on manner, “impeding their learning ability.”

Essentially, e-books are desensitizing us to the broad range of vocabulary and language available to us. It’s no wonder that some of our most-used words in conversation are delightfully complex vocables like “cool,” “like” and “whatever.” [divider type=””]

Causing a stir in the piracy department

Now that nearly every piece of writing ever is a PDF somewhere in the bowels of the internet, people are torrenting and downloading files as if they were movies. Or music. Or whatever other industry that has been milked by the impatient American public tempted by free stuff with no consequences.

Basically, people have been stealing more books in this past decade than in any other decade, according to an article in the March 2013 issue of TIME. (This, by the way, includes the era of communist China, in which books were physically robbed and burned.) Copies are limitless and illegal websites are only a click away, so the livelihoods of artists and authors are exploited by the vast population. E-books have turned us all into petty lawbreakers and idea-stealing young folk who have little respect for copyright.

A majority of teenagers, according to The Telegraph, simply do not understand that downloading a book illegally is roughly the same thing as breaking into a bookstore at midnight, shoving a book down your shirt and making a run for it. Now, on top of being shallow, we’re apathetic to the value of creative work. [divider type=””]

[quote_center]E-books have turned us all into petty lawbreakers.[/quote_center]

The verdict

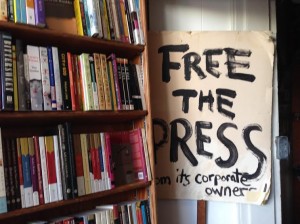

Don’t get me wrong, I love that e-books are cheaper and more accessible. But I’m against the idea that e-books are just another material commodity that can be monopolized by online corporate giants like Amazon. The fundamental problem is that our society and our economy can only see a book as an object created solely for profit.

In our capitalist world, it’s all too easy to view books as just another product to be cheapened and manipulated to fit that oh-so-elusive notion of “convenience.”

Meanwhile, countries such as Venezuela and China understand that print books are a basic staple of one’s cultural tapestry. In Venezuela, classic literature such as Cervantes’ Don Quixote is mass-printed and subsidized by the government before being distributed to schools and homes throughout the nation. And by distributed, I mean physically handed from one human being to another. Books become community.

So yes, e-books are good business. Nobody can deny that a 99-cent book is pretty miraculous. But at what cost? (No pun intended.)

We simply cannot allow convenience and economic advantage to reinvent our world, to rewire the way we read, the way we concentrate and absorb the words that surround us. Especially when the quest for convenience is literally chipping away at our ability to sit down and just read.

The rise of e-books mirrors our multitasking, hedonistic ways — and if books with actual paper and tough spines are a dying breed, then I’m not letting them go quietly.

Centuries from now, if the remaining paper books become so archaic and inaccessible that they are placed in vacuumed glass cubes and elevated on pedestals, I will personally find a way to retrieve the literature of the world while evading maximum security and becoming a world-class felon. Because in a society where the virtual and the physical blurs together, hard-bound books are the only real things I have left.