Criminologist Jackson Toby wrote in a 2001 issue of Weekly Standard that “although mass murders inside of American schools are statistically very, very rare, when they do occur, they are more likely to take place in good suburban schools than in bad inner-city schools.”

The same is true more than 10 years later. On Dec. 14, 2012, 20 children and six adults were fatally shot and killed at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn. Just one day prior to that, a bomb threat directed at an MVHS teacher was scrawled in graffiti at three schools in the Cupertino area.

“You always think of Cupertino as being a little twinkling bubble, but then this and the cement plant thing last year — it’s weird, like a wake up call,” said junior Allyson Gottlieb, a student of the MVHS teacher who was threatened in December. “We think, ‘Oh, it happened somewhere else. It’ll never happen here!’ And then stuff like this happens here.”

As identified by the Hartford Courant, over 80 percent of America’s 21 worst massacres happened in suburban or rural areas, as did each of the five worst school massacres.

The recent gun control legislation assumes that guns are the problem, but according to Toby, the shooters are the ones who need help. Toby writes, “The more exalted the reputation of a school, the worse it is for a student who feels trapped in such a school.”

It makes sense, then, that the first line of defense consists of those that spend the most time with these students: the teachers. Across the nation, including at MVHS, many teachers are taking the initiative to approach and help students who have difficulty engaging.

It makes sense, then, that the first line of defense consists of those that spend the most time with these students: the teachers. Across the nation, including at MVHS, many teachers are taking the initiative to approach and help students who have difficulty engaging.

English teacher Vennessa Nava relies on her personal observations of students’ interactions and behavior in the classroom, in particular looking to help those who seem quiet and less engaged. Yet Nava is also wary of speculation, since a quiet student’s disconnect may simply be a matter of personal preference and relationship.

“It almost becomes a tacit kind of process, where you just get a feeling about certain people … because some students gel with teachers and some students don’t gel with certain teachers,” Nava said. “As a teacher, I have to assess whether that student is going to be receptive to me being the one to reach out and say, ‘Hey, is everything okay?’”

School psychologist Sheila Altmann notes that there is no strict formula to detect warning signs that indicate a student is at risk. The susceptibility of a student depends on the specific stressors in his or her environment. Change of any sort can be particularly stressful, building pressure that gradually becomes more difficult to deal with.

“It’s very much individual factors,” Altmann said. “It could be genetic factors, constitutional factors, home environment, the stressors in their life … We know certain things about stressors that put people at risk. How [people] break down is different.”

While each student may need a different kind of help, the main goal, according to Altmann, is to prevent such incidents by maintaining a general state of psychological well-being, then working inward to help students individually.

“It’s like a funnel; if you have [psychological support] going on for all, you will have fewer that need that degree [of help]. No matter what we do, though, there are a certain amount of mental health problems,” Altmann said. “We’re not going to eliminate it 100 percent.”

Even simply identifying students that need help, especially with students whose problems are not as outwardly apparent, requires deep psychological thinking.

Even simply identifying students that need help, especially with students whose problems are not as outwardly apparent, requires deep psychological thinking.

“With the shooter at Sandy Hook, they had stuff all over the news about his psychological well-being. I’d love to know what the guy who [made the bomb threat] was thinking,” Gottlieb said. “But his name shouldn’t be equal to a celebrity’s name, where you don’t know the names of the victims.”

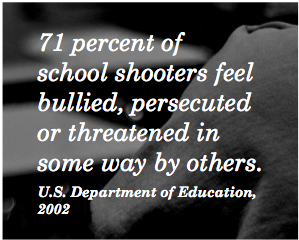

Yet it must be noted that often the problem starts with in-school bullying. In “The Final Report and Findings of the Safe School Initiative,” the Secret Service and U.S. Department of Education compiled crime statistics suggesting that 71 percent of school shooters felt bullied, persecuted or threatened in some way by others. And while there are many external factors, according to Nava, each individual case has to be examined in depth to prevent a potential shooting.

“It isn’t about the academics at that point; you need to make sure that the student is emotionally equipped to focus on school, but you need to take care of the emotional side first,” Nava said. “You have to start with the individual and open discussions there.”