During the process of brainstorming ideas for the project, Jain’s mentors at Stanford offered him many suggestions. That being said, Jain states that he was given much freedom to think through and recombine these concepts in his own way. Considering the fact that Jain’s lab had not yet touched upon the technology used to create the application, this opportunity was, according to Jain, truly once-in-a-lifetime.

“They literally said, ‘We’ve got a few high school interns coming in, and we’ve got some new components coming in, so let’s just give them to the interns and see what they do with it,’” Jain said. “They just threw everything on the table and said, ‘What do you think we can do with this? How can we innovate?’”

Over the span of two to three weeks, Jain programmed the application with guidance from one of his mentors at Stanford, production manager Matthew Hasel.

“This is the first year that we worked with a computer programmer,” Hasel said. “Usually we get our program work done by outside parties, but [Jain] gave us the opportunity to experiment.”

Although Jain, who began programming in the seventh grade, primarily coded the application himself, the magnitude of the project required the assistance of many other individuals from various fields of studies.

For instance, the first step in creating the application required the managing team to obtain CT scans from anonymous patient data through research clinics. Through software technology, programmers, such as Jain, then used that information to produce rough 3D models. Next, biomechanical illustrators touched up the models and added aesthetic corrections, and in the final stages, doctors and physiologists examined the models for any minor anatomical errors.

“There is no ‘I’ in science,” Jain said. “Everybody contributes.”

How it works

Using a compiler — a program that allows computer languages and codes to be compatible with multiple platforms — Jain is able to access his application on tablets such as the Apple iPad.

Among the 16,542 medical applications available through the Apple App store, Jain’s augmented reality application will be the first to introduce three dimensional models of human anatomy into real space when it is ready to be sold to the public.

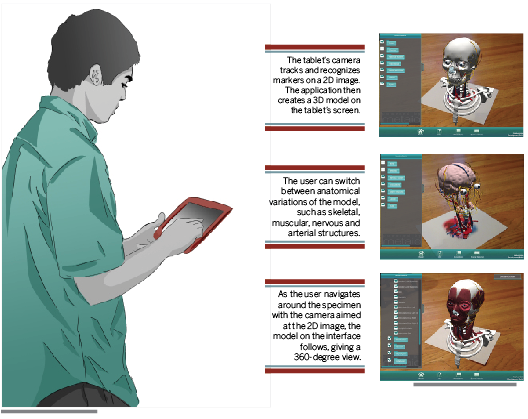

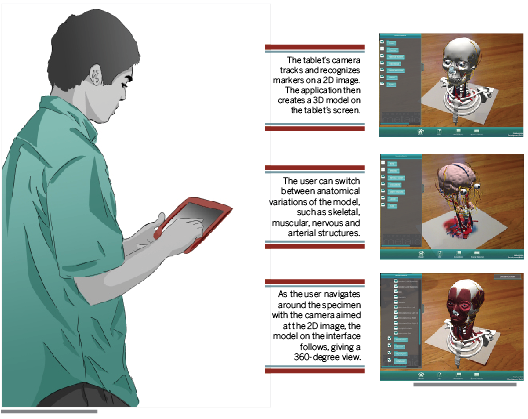

To use the application, image markers, which resemble QR codes, are placed on an image of a human body part. The tablet’s camera then tracks and recognizes image frame cells, triggering the application to project a 3D model of the image on the tablet’s screen.

Another feature that sets Jain’s augmented reality model apart from pre-existing applications is its ability to allow the user to switch between settings that display versatile views of the human specimen. Much like an online map that shows satellite, traffic and weather views, Jain’s application can impose skeletal, muscular, nervous and arterial structures onto the 3D model.

“[This] will highlight places of anatomy where it isn’t very visible to the average student,” Hasel said, “and increase learning in more visual and interactive ways.”

Discovering the connection

What interested Jain most about his research at Stanford was the fact that he was able to combine his interests in the fields of computer science and medicine into one entity by working in an interdisciplinary lab.

“Honestly, this application of computer science into medicine is something I’ve always dreamed of,” Jain said. “But I never really understood how it could come into reality until now.”

According to Jain, these types of endeavors are what science and even society are moving toward. One of Jain’s advisers at school, biology teacher Renee Fallon, similarly notes the mutual relationship between science and technology, seeing as she supports further integration of the two fields.

“It’s impossible to have science without technology,” Fallon said. “In general, students view each subject as its own [being], but that’s not the case at all.”

Moving forward

In the future, Jain hopes that his application will revolutionize the way human anatomy is taught by incorporating it into fundamental physiology lessons in high schools and middle schools with the access to such technology. According to Hasel, once the application is more developed, medical students could even use it to simulate surgical procedures.

“There would be image markers on both the dissection table and human cadaver,” Hasel said, “and the students would use their iPads to see under the skin without making any cuts.”

Though the school year has started, Jain is continuing his work at Stanford. Ultimately, Jain wants to further pursue the convergence of computer science and medicine. He finds it intriguing that until this point, the field has, for the most part, remained unexplored.

“There’s so much potential for innovation in this area,” Jain said. “It’s like a coin, and I get to experience both sides, heads and tails, medical and technological.”

Check out Jain’s application here!