More than half of AP U.S. History students team up on Google Docs to collectively succeed

More than half of AP U.S. History students team up on Google Docs to collectively succeed

It all began during the first week of school when students who had taken Advanced Placement U.S. History last year were invited to history teacher Margaret Platt’s classroom to offer advice to current students.

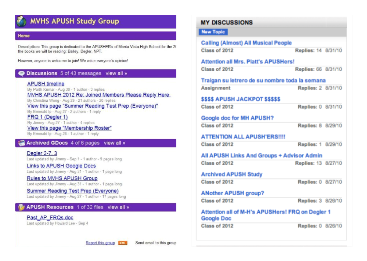

Enticed by the collaborative nature of Google Docs, Junior Taylor Shen spearheaded the movement for an online APUSH forum on Aug. 26. Within hours, 61 juniors had responded through School Loop and nine more had joined by the end of the week. By their first free-response question, Shen had 164 collaborators editing and viewing a single document made up of 15 pages.

“People would be dying to get [access],” junior Jimmy Chen said. “The page would block you because it’d say that there’s too many people trying to go in and they couldn’t let you in. You’d have to wait a couple minutes and try logging in again.”

Due to the large number of users, the first Google Doc was an anarchic concoction of themes, prompts, possible explanations, emoticons and confused questions in parenthesis.

Other APUSH students studying from the document experienced the chaos of 164 people editing one document and found it to be a disorderly hodgepodge of information.

“It hasn’t helped me,” junior Yehrin Park said. “It’s really [disorganized]. It’s just a lot of stuff crammed into one document.”

Chen and Shen hope to solve this problem by developing an administrative system to ensure content quality and organization, built upon dedicated students in charge of verifying information, organizing content and weeding out people who do not contribute. Platt sees some benefits to the students’ collaborations.

“This is a class that requires that kids outside of class talk about the content, talk about what they’re learning,” Platt said. “Anytime that they can do that—I applaud that. That’s how you learn. That’s how you make the material yours. You own it.”

Though her students’ enthusiasm for history excites her, she is concerned about what students are sharing.

“What I obviously don’t support is when kids are actually sharing information they’ve been assigned to do in class and they’re getting credit for it—that’s not appropriate,” Platt said. “I think the concept of kids becoming more and more reliant on cyberspace collaboration and communication sometimes blurs the line between, ‘Oh if I share this response to this question that Platt asked us in class with my buddy, is that cheating? Well, we’re just collaborating over it and talking about it.’ ”

Because online collaboration is a relatively new concept, no one has officially defined the difference between collaborating and cheating when you’re online with someone. Chen maintains that one cannot cheat while analyzing hypothetical prompts and outlining the texts.

Besides cheating, students face another issue with the use of Google Docs.

“It’s come to the point that solely studying from [the Google Doc] could actually benefit one significantly on the test, [so] it’s possible that we may [be] too reliant on the group,” Shen said. “We still [do] need to study on our own, this is just a supplement.”

Online collaboration transcends social groups and cliques. Chen believes that everyone is on the same playing field and everyone has an equal voice. Some introverted people may not have anyone to collaborate with, he explains, and using the Internet will let them.

“I’ve really seen a bunch of people open up and communicate more effectively,” Chen said. “It doesn’t matter who you are or whatever class, whatever group you hang out with, it’s more who you are and whatever you do to help contribute to the effort.”

{cc-by-ny}