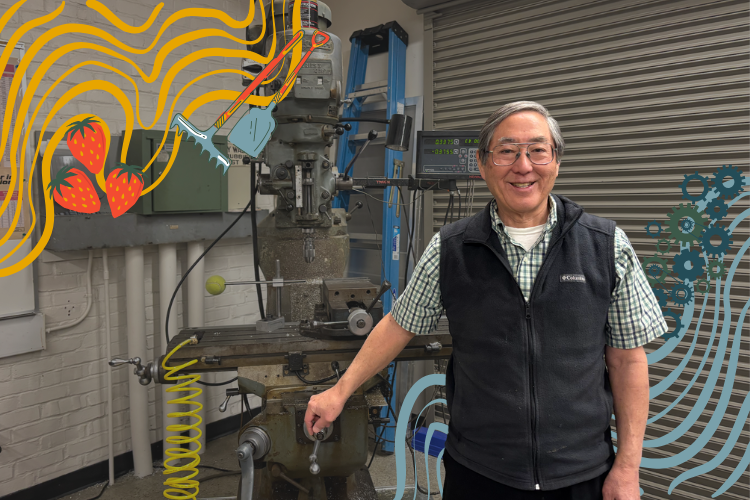

EE: Hi everyone! I’m Kathryn Foo and I’m going to be your host for today’s podcast. Today, we’re going to jump into the life of engineering teacher Ted Shinta, from being a strawberry farmer to working in the military and eventually becoming a machinist. Today, we’re going to explore more about his life prior to joining MVHS as an engineering teacher.

EE: Can you give me a little more insight into your childhood and your time on the strawberry farm? What was that like? Did you learn any lessons from that time?

TS: Well, things were different back then. The area we lived in, which is near Fremont and Sunnyvale — there’s actually an Arco gas station where our house was — used to be primarily orchards around us. It’s pretty good as a kid to grow up in that kind of environment. You can do whatever you want. Whenever my mom had to go to the farm, we would have to go to the farm, so I spent a lot of my time at the strawberry farm. Then, we would sometimes have jobs that my father would ask us to do. Sometimes early, like he wanted to encourage us to work, so he used to pay us.

EE: Can I ask how much you were paid?

TS: Whatever the minimum wage was at the time, probably like, 50 cents an hour, or something like that. It wasn’t a lot. The idea was to teach us about work and try to get us used to the idea of and the discipline of going up there and doing the job.

EE: Do you think you have any particular experience that you take from there, or something that stands out to you from then?

TS: My father tried to instill in us that working on the strawberry farm is hard labor, and you don’t want that to be what you do. You want to do more than the hard labor. It’s not pleasant. You don’t want to do it for your whole life.

EE: Can you give me more insight on your time in the army? What was that like, and what did it teach you?

TS: The training is hard, but that’s not the bad part. The bad part was when I went to the regular duty station, then I found, first of all, we’re under strength because they can’t get enough volunteers. Then, the second thing is, half of the guys there are guys who would have been in jail otherwise. They were given the option of joining the army this all-volunteer army, or going to jail, and so they joined the army. If you have that kind of background, your background is always in conflict with theirs. In other words, you’re always trying to “get over.” That’s what they’ll say. They want to get over on you, so that means that you have to fight. It’s that conflict all the time that I really didn’t like within the army itself with your supposed comrades in arms.

EE: How did you get interested in machining and become that initial job as a machinist?

TS: Well, when I got out of the army, I was pretty upset. The army was not a pleasant experience for me. I was so angry at the time, I honestly didn’t think that I was employable. Then coincidentally, my sister had been taking a program in clothing design in Los Angeles, and she had just graduated, so she was coming up looking for a job, and she was going to the California Employment Department. She said, “Well, I’m going, why don’t you go along, you know?” That was the sort of support that I needed at the time. I went over with her that day to CED. Right away, you go up to the window, and she goes, “What are you interested in?” I go, “I don’t know. I’m interested in my firearms. If I could do something that’s like gun-smithing, that would be interesting to me.” The woman said, “Well, we don’t have that, but we have this machining program. It’s an internship training program through De Anza.” I started taking classes at De Anza, then after I finished that program, we were offered a chance to do an internship at NASA, where I worked at NASA for a little over two years.

TS: I decided to apply to San Jose State. When I got in, my intention was to study part time while I was working and then complete my degree. But switching from economics to mechanical engineering meant that I had to take all the engineering classes. My father asked me how long it would take. “Maybe 10-15 years.” He’s going, “Well, if you want to, I’ll pay for you to go. I’ll pay your expenses if you go full-time.” I did go full-time. It’s kind of a long story, but my father and I did not get along, but he wanted to get me through college. He wanted me to have a degree because, his parents were not educated, but they got him through high school, and then it was his duty to get us through college.

EE: The last question I have is, going through the different experiences that you’ve had — whether it be as a farmer, as an engineer, as an infantryman — what are some life lessons that you’ve taken away from each of these jobs? What advice would you give to high schoolers who are just starting their future?

TS: Like I mentioned before, I had a conflict with my father, and he’s always called me a loser because I want to stand on principle all the time. If I thought something was right, I wasn’t going to compromise. In real life, you have to look at the situation and be flexible and resilient, because things are going to happen that you don’t really want to be part of, or that you have no control over, but the better thing to do is to get along. It took me a long time to realize that this thing that my father was saying, that I was a loser, was true in that getting indignant and saying, “I won’t do it.” is not really smart. It’s better to be smart about stuff, not to be self-destructive.

EE: That’s it for today’s episode. Thank you so much Mr. Shinta for sitting down with me and letting me hear more about your life!