The first thing U.S. veteran Philip Wayne Arroyo Jr. sees as he steps through the doorway is the fiery explosion of burning gunpowder and gas. To his right, the muzzle of an AK-47 is pointed at him. Gunshots ring and Arroyo jerks his firearm to the right, trying to aim, but a bullet strikes him like a kick to the chest. Muscle memory from his close quarter combat training takes over. He falls to the ground and rolls to the left to prevent his body from blocking the doorway, which could put his entire team at risk. The man behind Arroyo surges in and kills the attacker.

CQC training was a regular part of daily operations for the 10th Mountain Division, the light infantry unit Arroyo served under in Afghanistan. A few months prior, 18-year-old Arroyo never imagined he would be serving in Afghanistan. Arroyo’s mother, Diana Satele, recalled that he enlisted before the 9/11 attacks to make money for college with hopes of becoming a police officer after graduation.

“I remember when the 9/11 bombings happened,” Satele said. “Knowing that Philip was in the military, when I turned on the news and saw what happened to the Twin Towers, I knew that he was going to go to Afghanistan. And that was frightful. My whole family, my mom, my sister and I were crying knowing that he was going to go to war.”

Even after Arroyo returned, he was tormented by his time at war. Arroyo would have flashbacks of his most traumatic memories, moments so vivid they felt indistinguishable from reality. He flinched at the sound of fireworks because they sounded like gunshots. He refused to walk on grass, a habit from Afghanistan because even a step off the path could mean stepping on a landmine. He would avoid the mailman, afraid he would be sent back to combat.

At night, his symptoms worsened. Nightmares of his war experiences and the violence he witnessed plagued his sleep, so he often drank and played video games until 3 a.m. He believed he would have to live the rest of his life like this. Retired colonel Arturo Thiele-Sardina agrees that many veterans are deeply changed when they return from war, often unable to even speak about deployment. His uncle, who served in World War II, never spoke about his time in the military until Sardina grew up and joined the military himself. These are all symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, which, according to the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, 15% of deployed veterans struggle with.

“The government trains our soldiers how to fix their guns, clean their guns, how to shoot their guns — but they didn’t give my son any training on how to come back to a civilized world,” Satele said. “These men were suffering and we did not know how to help them. Some of them may have married young, and now there’s a young wife who doesn’t know how to deal with her husband who’s having post traumatic stress. Also, mothers who were taking the kids back, unless they were familiar with medical stuff, how would they know how to help their kids? They left us to figure that out ourselves.”

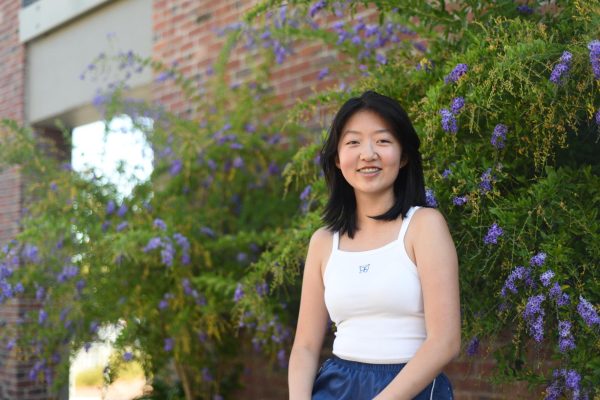

Eleven years after Arroyo left the military, he applied for veterans’ benefits. The VA had no record of Arroyo’s deployment, forcing him to contact various people he served with for a written account that he was in Afghanistan. Arroyo applied four times, with each application taking several months, before finally receiving a 100% disability rating from the VA for his PTSD in 2019. A disability rating determines both the severity of a veteran’s condition and the compensation they receive. After regularly visiting a therapist, discovering Christianity and joining the pickleball community at Memorial Park, Arroyo escaped his cycle of alcohol and video games.

But according to Arroyo, being denied a disability rating was a “horrible process,” as veterans felt like the trauma they endure is being invalidated. Three of his friends died by suicide after their disability ratings were denied. After receiving his full disability rating, Arroyo now spends time helping other veterans navigate the VA.

“When I help my friends, I don’t ask for a dime,” Arroyo said. “It’s that old mentality that as a veteran, you have to take care of your buddy. Because my buddies passed away, they’re not going to get their benefits. The way I see it, the government just got off scot free for not paying dues on those individuals. I’m trying to get them through the system so they can get what they’re owed and we’re not feeling mistreated.”

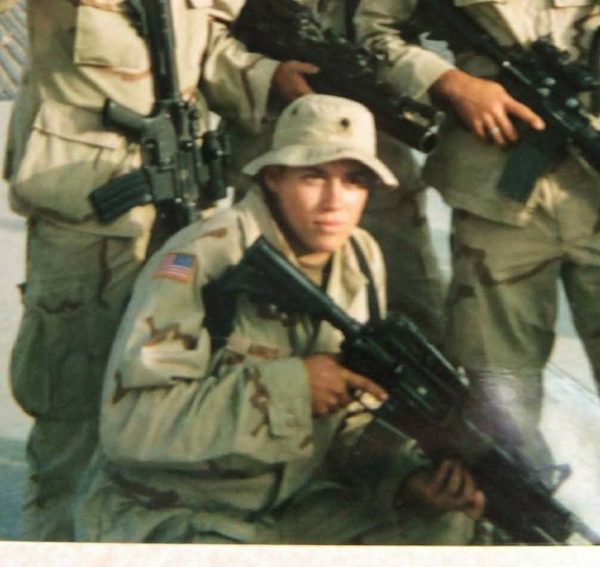

Sardina says this mindset of helping fellow veterans is something characteristic of the military — a bond forged through shared experiences and the understanding that no one else can fully grasp what they’ve endured. He joined the American Legion, an organization comprised of veterans or active military dedicated to supporting veterans and community.

“You may be Black, you may be Asian, you may be from wherever,” Sardina said. “The military reflects what this country is. We’re one of many and we work together as a team. I’m not going to let you down, you’re not going to let me down, because nothing is worse than letting down one of your teammates. You may be a Democrat, I may be Republican, but at the end of the day, we’re Americans. We all want our country to succeed.”