Surrounded by die-hard fans, blaring speakers and elements of punk-rock, Kennedy Middle School history teacher Ami Byrne could only describe what she had just seen, heard and felt as a transformative experience. The year was 1994, and after just having moved to California, Byrne would go to her first ever concert — watching lead singer Henry Rollins of Rollins Band perform at the Greek Amphitheater in Berkeley, Calif. This concert started her unwavering love for the ultimate concert experience.

“The experience was crazy, since I had never been to a concert since moving from Oklahoma, where we didn’t get concerts,” Byrne said. “You had the pit, which was a legit pit, unlike today, where it’s just a crowd of people standing on the floor — that is not a pit. I just remember thinking, ‘Holy cow, what planet have I landed on?'”

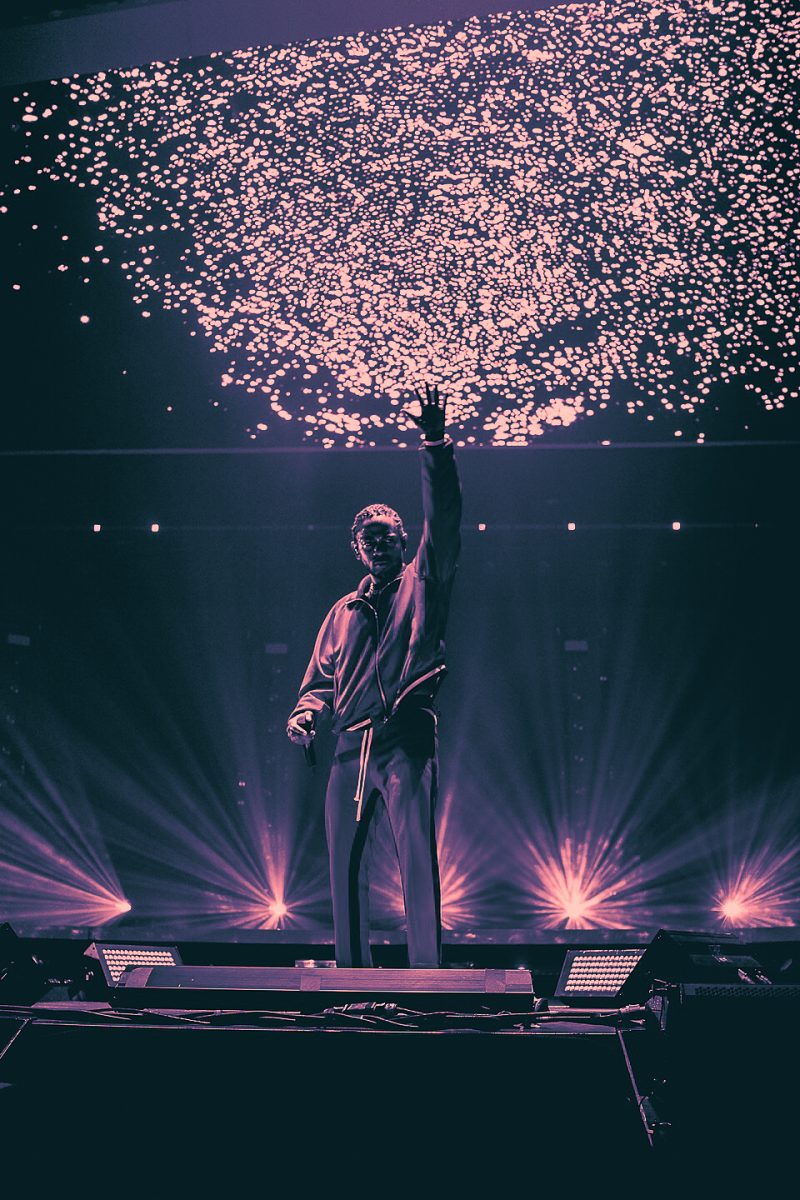

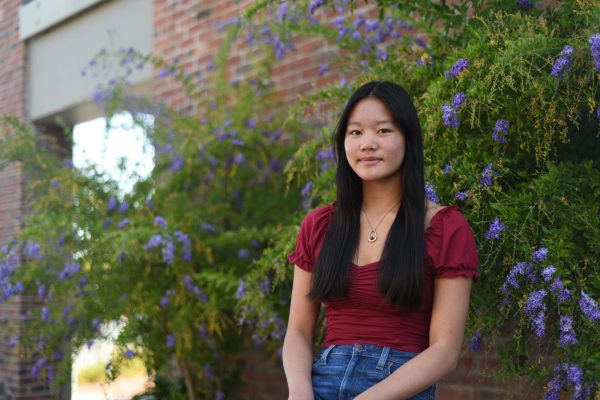

Thirty-one years after her first concert experience, Byrne still enjoys exploring concerts of all different genres, whether they’re hip-hop productions like Kendrick Lamar’s or alternative indie performances like Björk’s. Having attended several concerts around the world, from Taylor Swift in Vancouver to NJZ (formerly known as NewJeans) in Tokyo, MVHS ’24 alum Sapphire Yang expresses sentiments similar to Byrne’s.

“I go to concerts because being able to see some of my favorite artists live is super thrilling,” Yang said. “The experience is always different for each one — it’s a different group of fans each time, so the energy is different for each concert.”

Concerts have always been a popular attraction for fans looking to interact with not only artists but also a community of people with a common interest. Byrne particularly appreciates this aspect of concerts, commenting on the potential of making new friends through shared experiences and bonding over songs.

“I love live music, and I go to lots of different kinds of shows just because I like the live music experience of being in a room with a performer that I enjoy, whether it’s someone getting their career started or a big production,” Byrne said. “I don’t know how much longer I’ll keep going, but I enjoy going just for that camaraderie and feeling of, ‘Wow, there they are.'”

Although concert demand has stayed robust, the ticketing experience hasn’t been as linear. Concertgoers used to typically line up in person at a venue’s box office or area retailers in hopes of securing a seat, often standing in line for hours just to leave empty-handed if tickets sold out. While seemingly an aggravating and tedious process to attend a concert, Byrne attributes the old-school way of buying concert tickets as a fuller experience that can be cherished long past the concert date.

“The coolest thing about going to a concert back in the day was that you had your ticket, and that was your souvenir,” Byrne said. “You would stand in line and wait, and if the tickets were gone, they were gone. But then you could buy from the scalpers standing outside the shows, so paper was the way to go. And you could talk to other fans and people going to the show. It was more of a community.”

As the digital era started to expand after the turn of the century, Ticketmaster became the primary form of ticket sales, ultimately monopolizing the industry in terms of both selling tickets and advertising venues. In contrast to buying in-person, a digital queue allows for a higher capacity of prospective concertgoers to find tickets and quicker service. But to Byrne and Yang, an overload of activity by thousands of people on the same website can cause large queue numbers and website crashes that promote unhealthy anxiety. However, whereas this process is extremely stressful for Yang, junior Vivana Dave has opposing opinions, viewing the same experience positively.

“It’s thrilling just being in that queue and anticipating whether or not you’re going to be able to get a good seat,” Dave said. “I worry if it’s going to be too expensive and if my parents are going to even let me buy the tickets, but getting the tickets is a big deal to me.“

Additionally, not only has the ticketing experience evolved to become streamlined digitally by a singular ticketing system, but buying tickets to concerts has also been affected by an even bigger factor — price. Byrne, who remembers going to bands such as the Beastie Boys and The Cure for $50 and $70 respectively, now pays $300 on average for a ticket at a similar seat. In conjunction with inflation affecting the music industry heavily over the 21st century, Ticketmaster has added additional venue fees that Byrne finds hinder the accessibility of concerts as a whole.

“Now with all the added fees, young people can’t go to concerts anymore, and they can’t get exposed to live music at a younger age, which affects the energy of the audience too,” Byrne said. “When you’re sitting around a bunch of people that had the money to buy the tickets and they don’t seem into the show, it’s really frustrating and can impact your experience too. So it really makes me sad that young people aren’t often able to go to big productions.”

Many of these ticket pricing issues also stem from scalpers, who purchase tickets solely to resell them for marked-up prices in hopes of profit. To combat such practices, Yang suggests stricter control on what prices vendors can list to prevent stiff resales and keep ticket prices accessible for the general public.

“In terms of reselling, sites like Ticketmaster should only allow resale on their official platform, and they can only resell for the price they bought for,” Yang said. “This could greatly reduce the amount of scalpers there are.”

Despite potential changes to the ticketing experience, concertgoers still face a plethora of concerns, including audience etiquette, which has recently been a prominent issue. Incidents involving poor concert etiquette have risen in frequency after the COVID-19 pandemic, such as when fans screamed at inappropriate times and threw objects onstage at artist beabadoobee’s tour. Yang believes that an incident with concert etiquette can not only affect her experience with the concert itself but deteriorate her enjoyment of the artist in the future — negative experiences with other fans leave a lasting impression on the artist, regardless of the nature of the incident.

“Not being able to see the actual performer ruins the concert experience,” Yang said. “Instead of being able to fully enjoy the concert, I get frustrated that I paid money to see the back of somebody else’s poster.”

In addition to Yang’s concern about other fans being rude, Byrne feels that there has been a decrease in assistance when someone is injured. With people passing out from dehydration, Byrne has witnessed an increase in the lack of care for others around them, attributing this to the gradual loss of social awareness as concert audiences become younger. Overall, their concern for the potential inconsistency of the concert experience poses a question that dives deeper than just ticketing issues — is all the effort it takes to secure a concert seat worth it if there’s a possibility of another concertgoer ruining the entire experience?

“There’s this lack of empathy that feels like people are just meaner and don’t have that common courtesy or humanity that was prevalent in the past,” Byrne said. “It’s frustrating to see somebody hurt or suffering, and that people are not trying to help them. And an experience can turn negative for anyone if there’s something that ran out that makes you think you got slighted or evokes any feeling of jealousy. So that causes that ability to develop empathy to be really tainted — just trying to see that common experience and that commonality between us as people rather than everyone for themselves — can be hard.”