When sophomore Banan Badran first walked into her World History classroom, the first detail that caught her eye were the variety of flags from countries from all over the world that hung on the four walls of the room. She expected the curriculum to be as diverse as the decorated classroom was. However, as it nears the end of the first semester of her history class, Badran finds her expectations of the class to be unfulfilled. Badran notes how the class only discusses certain parts of the world in depth, specifically European countries, leaving other parts undiscussed.

“Some teachers do talk about conflicts around the world,” Badran said. “But they only talk about certain conflicts. For example, they haven’t even mentioned the Middle East and the conflicts that are going on there, but they focus on, for example, the Ukraine-Russian war.”

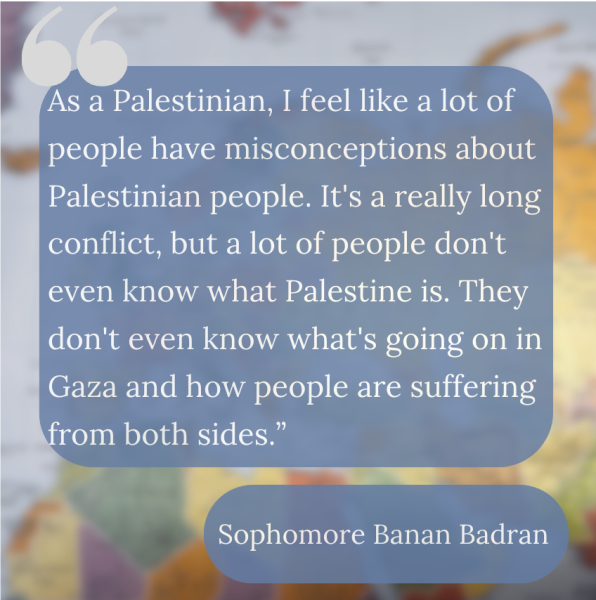

As someone who identifies as Palestinian, Badran often finds herself frustrated with the history curriculum at MVHS for not educating the student population about the long-standing history behind the conflicts that are currently occurring in the area.

“As a Palestinian, I feel like a lot of people have misconceptions about Palestinian people,” Badran said. “And it’s a really long conflict, but a lot of people don’t even know what Palestine is. They don’t even know what’s going on in Gaza and how people are suffering from both sides.”

Sophomore Jagriti Parimi also believes that even though the curriculum makes an effort to explore a diverse range of countries, the perspective is often made with a connection to a European country that may convey a biased version of the history.

“We have started learning about different countries but it branched off of European countries,” Parimi said. “We started with learning about countries in Europe and then it branched how Europe colonized other countries, so we only learn about that but not the exact history of those countries before they were colonized.”

Parimi believes that highlighting European influence on a country instead of having a more holistic view can lead to students developing a biased or even incorrect view of the world. She also argues that in an ethnically and racially diverse school like MVHS, the history curriculum should be adjusted to encompass a vaster view of the world.

“It focuses more on one particular country or nation, and we don’t have a lot of background knowledge and we are learning a lot about Europe so we don’t have history about other countries,” Parimi said. “It’s weird since a lot of people in MVHS are from different countries rather than Europe and they are not learning about their own history. It can impact how they see their own country or nation.”

World History teacher Robyn Brostowicz also agrees with Parimi and Badran about the work that needs to be done in order to bring more inclusivity to the World History curriculum. However, she believes that MVHS and the district have come a long way in their efforts to improve the history curriculum.

“For World History specifically, we definitely have tried to branch out from it being too Eurocentric, which is what the state standards had seemed to be,” Brostowicz said. “But we have found ways to incorporate different perspectives, different experiences within the different units that we study, whether it be minority voices and experiences, and women, changes that have taken place in terms of rights around the world for different people. We certainly have branched out to different regions of the world as well, in order to cover more of the globe.”

Regardless of the significant improvement from past years, Brostowicz continues to implement other strategies such as using sources other than the textbook and having designated lessons that ensure that minority voices are exemplified. She argues that the best lesson the history curriculum has to offer its students is the ability to recognize the holes in what they learn in the class.

“It’s important to also consider the voices that aren’t in the textbook by using supplemental primary sources and making sure that students are aware to supplement the curriculum on their own,” Brostowicz said. “Also to constantly be looking for a different angle or different perspective and making sure that they are looking beyond my classroom and at current events and that people are a little bit more well-rounded in how they see things.”

When it comes to continuing to diversify the class, Parimi suggests that the way that the curriculum tackles teaching about different countries needs to be adjusted. Instead of branching offEuropean history, Parimi argues that the curriculum should delve into the history of each country separately before studying how they intersect with each other.

“We learn about French history during the 17th Century and then we learn about Chinese history in the 19th or 20th Century,” Parimi said. “But I feel like it would be better if we talked about the countries during the same time period. We would have a better idea of what was happening in the world at the same time.”

Nevertheless, as the history curriculum develops over time, Brostowicz believes that she andher colleagues are continuing to do their best to include as much as possible in the short time they have. As of now, their main goal is to continue to give the students the tools and awareness to develop their own skills to learn from the past.

“The world is a very big place, and there’s only so much time that we have together in regards to studying world history, and so we do what we can with the time that we have and hopefully give students the skills to find the holes in the story and supplement them on their own,” Brostowicz said. “I think we’re continually evolving. I think that my colleagues in the World History department have certainly made it a priority and an effort, and we are always sharing resources and ideas. So I think that we are at least doing the work and, hopefully, we’ll continue to do so.”