Japanese language students at MVHS have campaigned to keep the Japanese language courses amidst FUHSD’s plans to phase the course out. In April of 2023, the district announced that the Japanese program at MVHS would be phased out starting in the 2024-2025 school year and finishing in the 2028-2029 school year. In order to keep enrollment in language courses sufficient as total enrollment decreases across FUHSD schools, one language course will be phased out in each FUHSD school except for LHS and HHS which have healthy enrollment in their modern language programs.

Sugahara Yuriko, a researcher at the Consulate of Japan in San Francisco, initially contacted MVHS Japanese teacher Chiaki Vanasupa in April 2024, encouraging Vanasupa to push the district to keep Japanese. As early as April 2023 the Consulate knew about the plan to phase out Japanese classes in FUHSD. Yuriko asked whether there was student interest in keeping the curriculum, allowing the consulate to help the students by spreading awareness about their situation and connecting them to organizations that are willing to help.

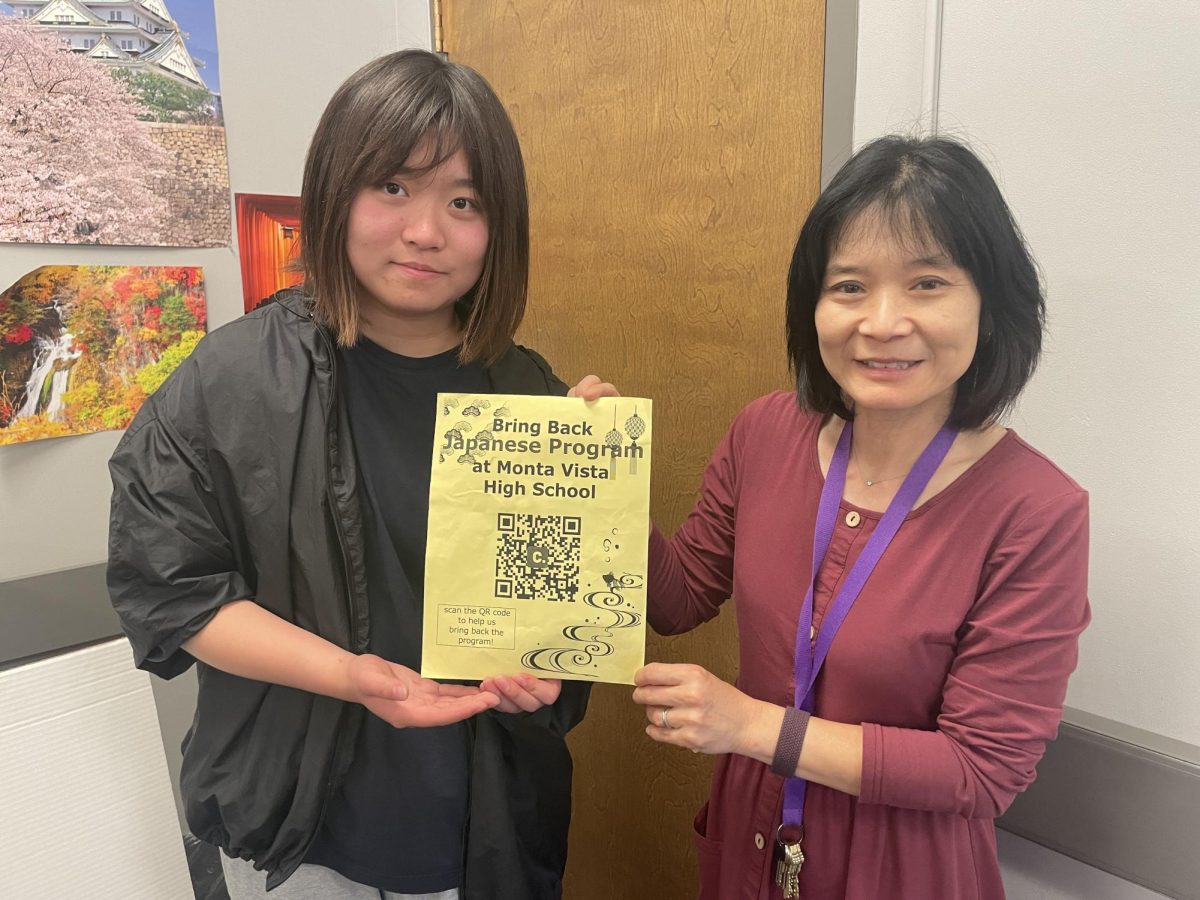

At MVHS, senior and Japanese student Momoka Kume created an online petition to keep the course, which has received 518 signatures at the time of publication. Additionally, Japanese students posted flyers around campus with a QR Code linking to the petition.

According to Yuriko, the movement to preserve Japanese classes first started at Cupertino High School, whose Japanese program faces the same plans. Japanese students at CHS created a petition on June 11. After suggestion from the former president of national association of Japanese language teachers Ann Jordan, the two high schools put the two groups in contact to discuss their plans to retain Japanese. According to senior and Japanese student Rongyi Lin, CHS and MVHS students will present their case to the district during the Nov. 12 district board meeting in hopes that the district will change its mind. Lin hopes that the data they are collecting about interest in taking Japanese at MVHS such as the petition can be used to persuade the district to retain the course.

“I think we’ll be fairly successful,” Lin said. “There are two pretty major schools working together, and I don’t think we have a resource shortage. I think the district is primarily citing declining enrollment, but if we can prove that people will take Japanese classes, then it should be OK.”

Yuriko has been able to connect them with many other Japanese associations like the American Association of Japanese Teachers because she is from the Japanese consulate, an organization that represents Japan and assists its citizens abroad. She emphasizes the fact that students’ voices are the most important component of this campaign.

“If it’s just the students and teachers, there may be a limit to the network that they can create, like expanding on that support network,” Yuriko said. “So that’s where people who are part of that community who want to support the Japanese language program can support it. So that would be Sister City associations, Japanese companies or our office at the consulate. We’re just a part of one of the many actors that want to support the people at the core.”

Although Kume, Lin and Yuriko all remain hopeful that the district’s decision will be overturned, Superintendent Graham Clark notes that there are a multitude of issues with keeping Japanese courses amidst declining enrollment. One issue is overstaffing, which Clark says can cost the district $40,000 to $50,000 per class period, also known as a section.

The number of Japanese students in the program last year was 111, which Clark believes is too low. Teacher contracts aim for an average class size of 32.5 students, so five sections of Japanese class would require a minimum of 160 students. He says that the district is unlikely to change course unless the MVHS program can show that it has enough students to fill Japanese levels one through AP.

The district’s problems don’t stop at budgeting concerns, though: Clark also notes that scheduling is a challenge for schools facing declining enrollment. When courses like Japanese lack student enrollment, the school has fewer classes of the subject, which can make student course scheduling for the district challenging. The problem is exacerbated with higher level classes—such as AP classes like AP Japanese or AP Chemistry—that are more selective and thus have very few students enrolled in them. This can lead to classes that are offered only once a day called singletons, which create class scheduling conflicts.

“At MVHS we have about 30 singletons, and there are only seven periods,” Clark said. “So that means in any given period, you’re going to have three or four classes that are offered once a day. So if you request those two classes, you have to make a choice. The more singletons you have, the harder it is to schedule.”

Clark states that he doesn’t want to phase out Japanese and is only making this decision due to declining enrollment. However, supporters of the movement to retain Japanese – such as Japanese teacher Chiaki Vanasupa – believe that the district won’t consider the consequences of phasing out the Japanese program.

“The district phasing out the Japanese program doesn’t help anything,” Vanasupa said. “And the district won’t consider the importance of keeping the Japanese program and the language programs. There’s a lot of benefits, and instead of this, because of financial issues, they’ll cut the Japanese program.”

According to Kume, one benefit of the Japanese program is the sense of community it provides to its students, which she says could be in jeopardy for newer students because of Japanese 1 being phased out.

“Japanese is important for me because I was born in Japan, and I also like Japanese culture a lot,” Kume said. “I like to communicate with people who like Japanese culture, and I think Japanese culture can create a nice community. I hope new students can also have that kind of community.”

Though Vanasupa was hired as a temporary teacher due to Japanese being phased out, her priority is saving the program.

“I don’t know about my job,” Vanasupa said. “It’s OK, as long as I help the Japanese program. I really have to do it, it’s my mission. It’s challenging, I have no idea how the district will respond, but it’s better than not doing anything and just being quiet and just letting it phase out. I need to do something, regardless of the result.”