Colleges nationwide have been reinstating the SAT as an application requirement for the next admissions year as an update to test-optional policies created during the COVID era. Schools like Yale, Dartmouth, UT Austin and Brown have announced that they will adopt a test-mandatory policy moving forward.

Colleges have cited recent research suggesting that an optional SAT hurts underserved students, as standardized tests provide more accurate insight into students’ readiness for college than grades. Research and policy institute Opportunity Insights found little correlation between high school GPA and academic success in college, but claims that students from different socioeconomic backgrounds who have similar SAT or ACT scores have comparable grades in college. Standardized test scores have also become more reliable given the recent rise of grade inflation in many high schools, as the difficulty of attaining a 4.0 GPA differs from school to school.

In a statement announcing Yale’s decision to require standardized test scores for the next admissions cycle, Yale’s Dean of Undergraduate Admissions stated that applications without SAT scores provided “scant evidence of their readiness for Yale,” claiming that standardized test scores are the “single greatest predictor” of a student’s performance in Yale courses.

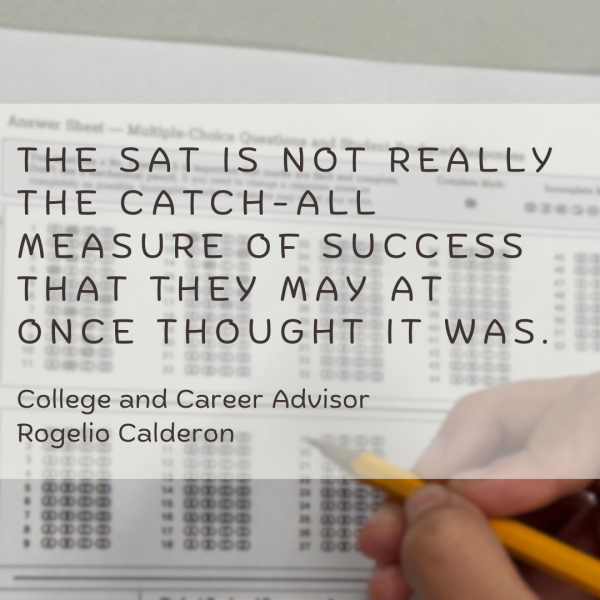

However, College and Career Advisor Rogelio Calderon views this research with skepticism. He says test scores are not always indicative of a student’s success in college, referencing the test-blind policies used by UCs and CSUs as an example that standardized test scores may not be a necessary factor when determining components of success.

“For the UCs and CSUs system, they came to the conclusion that the SAT is not really the catch-all measure of success that they may at once thought it was,” Calderon said. “There are other ways to measure academic success for students than a standardized test.”

“For the UCs and CSUs system, they came to the conclusion that the SAT is not really the catch-all measure of success that they may at once thought it was,” Calderon said. “There are other ways to measure academic success for students than a standardized test.”

Former UC Admissions Officer Sylvia Leong agrees with Calderon’s perspective that the SAT no longer accurately reflects a student’s readiness for college as it did in the past. Although she concedes that SAT scores may show potential, she notes that most colleges now look for a holistic review of a student by examining extracurriculars and activities. Thus, she does not believe test-mandatory policies would make a huge difference in admissions, as college admissions are “about looking at the student as a whole.”

In addition to holistic review, Leong says that during her time as a UC admissions officer, she had to take into consideration the region students were applying from. MVHS students, for example, would be compared to other students in FUHSD, not students from disadvantaged areas or from schools with different educational opportunities.

“Any test prep is its own cottage industry now,” Leong said. “You automatically have an advantage if you have parents who can afford to send their kids to test prep. Students who have the ability to take test prep classes will often score higher than those who haven’t. Socioeconomic status has to factor into the application as well.”

Junior Hursh Shah believes that there are some positives in the move to reinstate SAT requirements. He cites grade inflation’s effect of devaluing students’ GPAs, thus leading him to believe some standardization is necessary. According to Shah, if colleges look at GPA over SAT, MVHS students would be at a disadvantage compared to schools with higher grade inflation.

“I used to be at a school in Chicago when I was a sophomore, and there was very high grade inflation in terms of the grading system being very easy and lenient to the point where it wasn’t hard to get an A,” Shah said. “GPA is not a very good indicator of college readiness versus at least the SAT, where there’s some level of standardization amongst all students.”

Although Shah says SAT scores may be a better indicator of future success in college than a student’s GPA, he agrees that SAT requirements might also harm students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, especially due to the digital SAT requiring internet access and devices. Calderon agrees with this sentiment, adding that access to testing centers may act as another barrier for students.

“Some students don’t have close proximity to testing centers. For example, the SATs have limited the number of testing sites due to COVID, and even now, it’s still hard to find a lot of close testing sites for many students,” Calderon said. “So I think that access definitely does impact whether a student can take an SAT test or cannot, and that might also be a reason why a student might go test optional or choose not to, because they maybe just don’t have the closest testing center or they don’t have access to going there. So I do think that will impact students, especially those who already have significant socioeconomic barriers.”

Ultimately, Calderon states that not one component can fully predict a student’s future success and that both academic and non-academic factors can act as indicators of a student’s college readiness. He says that the colleges’ change in policies has no clear right or wrong choice.

“But then again, that’s not to say that there is no value in standardized testing because many schools have gone back to that or have it as a requirement because they still see value,” Calderon said. “So it’s really subjective. This whole standardized testing is really subjective. But I think that in the past few years, we’ve seen the landscape shift in ways where before we hadn’t seen that.”