For many people who grew up in the Bay Area, getting into college may seem like the pinnacle of a high schooler’s first 18 years of life. Getting into an Ivy League school raises students to the status of urban legend that the school will gossip about for the next year, and many are desperately scrambling to get into a college that may prevent their ancestors from turning over dead in the graves from displeasure.

Among our college frenzy, the Ivy-plus schools — meaning the Ivies, Stanford, University of Chicago and MIT — are especially in high demand. As applicants multiply year after year and the number of admissions remain the same, the admission rate significantly drops each year, leading to arguments surrounding anything that could shift admissions in your favor by even the slightest margin, whether it be affirmative action, which was recently struck down by the Supreme Court, or legacy admissions.

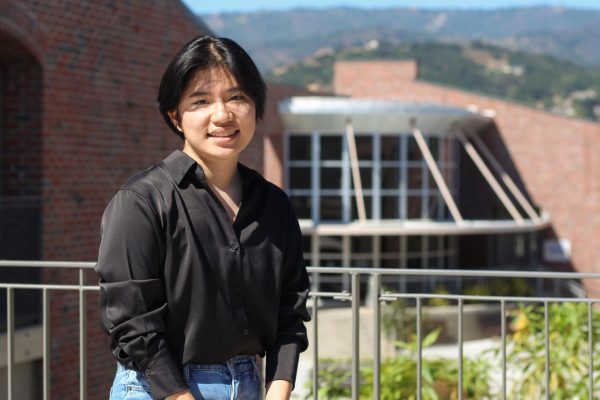

A study released just earlier this year exposed the egregious yet not unsuspected idea that elite colleges, such as Harvard, are significantly more likely to admit children from richer families compared to those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged. Although wealth is indeed correlated to standardized testing scores, this study found that even among students who received the same scores on tests like the SAT or ACT, applicants in the top 1% of family income are up to 55% more likely to be admitted than those from middle-class families in the 70th to 80th percentile of family income.

There is a stark difference between these elite Ivy-plus schools and highly selective public schools, such as the Universities of California, whose acceptance rate for lower and higher-income families is the same. The Ivy-plus colleges’ acceptance of more affluent students includes legacy admissions and recruited athletes, both of whom more commonly come from richer families. And thinking realistically, there are only so many spots to fill in the first place.

So the ultimate question is, why can’t these colleges just admit more people? While you could argue about endowments — the funding for most universities — and the increasing number of applicants, the reason it won’t happen boils down to this: elite colleges operate on a model of exclusivity, not inclusivity. They are desirable because they are exclusive, and thus, it would be counterproductive for them to admit more people.

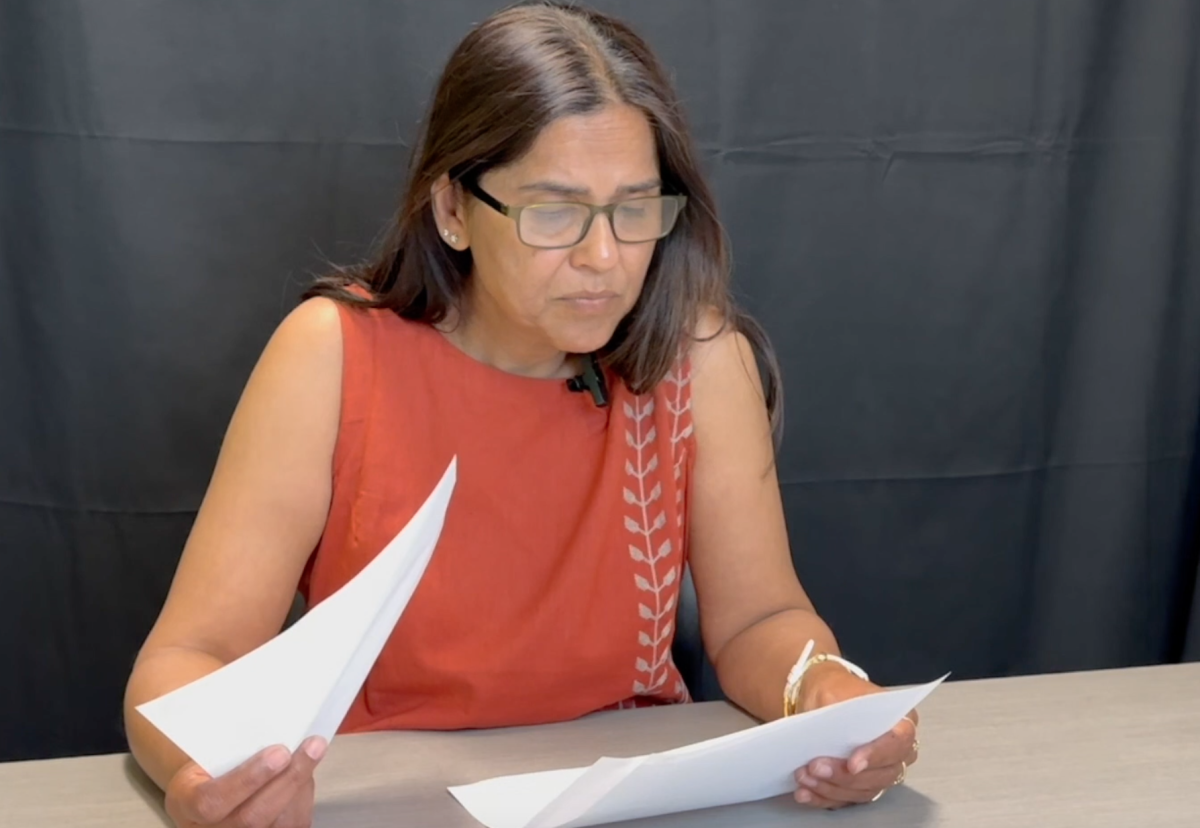

With all this in mind, one has to ask whether the American education system has lost track of its original purpose: to educate. College is no longer as simple as it used to be. Instead, it’s become a business — one that has become a minefield of status symbols and prestige. It’s a system that favors the rich and validates itself on the premise of its elitism.

And the worst thing is, we’re buying into that system. We’re buying into the glamor of exclusivity and the value of the prestige that comes with it. We treat the people who get into Ivy League schools as gods among men, and parents enforce the goal of getting into prestigious universities as the climax of high school.

There’s no logical reason for it. After all, it’s not necessary to attend a prestigious school to succeed in life: there have been plenty of people who are considered traditionally successful who didn’t go to an Ivy League school. Students place so much emphasis on an undergraduate college when 61.8% of a survey of 1931 MVHS students plan to apply, and 31.8% are considering applying for graduate school, which ultimately has a much more significant impact on their future job prospects.

So, why are we so invested in being a part of a system that doesn’t want the best for us in return?

That isn’t to say that you shouldn’t attend Cornell or Harvard or Stanford if you get in or that you shouldn’t apply. In many aspects, these colleges still provide some of the best educational opportunities you can find. But this shining golden image that our community paints of these colleges as untouchable pillars of academia isn’t correct. They have their flaws, and these deficits should be acknowledged. And even as we bemoan the difficulty of applying to Ivy-plus colleges, remember that we are among the privileged.

The median income of Cupertino hovers around $200,000, which puts us into the high-earning 90th percentile of family income in America. We are the very people who hold an advantage, and the seemingly limitless money we willingly spend on application fees proves that – and that’s something we should keep in mind as we apply to college.

And however it turns out, let me posit a theory: it’s not the college that makes the person, but the person who makes the college. You’re the one who dictates your college experience – take charge of that.