And the Oscar goes to…

Examining how international films are popularizing in America

The Oscars have diversified over the years, nominating more global films in categories other than Best International Foreign Feature

April 14, 2023

“Once you overcome the 1-inch-tall barrier of subtitles, you will be introduced to so many more amazing films” — Bong Joon-ho, Director of “Parasite.”

When “Parasite” swept the Oscars in 2020, literature teacher Monica Jariwala was excited to find out that it was possible for an international film to win “Best Picture” at the world’s most prestigious film award show. Later on, “Parasite” was added to the Contemporary Literature curriculum as one of the films the class would analyze.

“We’re all using [‘Parasite’] in our Contemporary Film Unit because it’s so interesting,” Jariwala said. “There’s so many layers about [social] class [and] the psychology of characters when they’re put in situations that push and test their limits. There’s also really beautiful cinematography and editing. And one of the expectations for [the unit] in the past couple of years has been to really diversify, and to show students films that are different [and] more representative of our growing, diverse school body but also just the world that we live in.”

The awards show telecast has only become more inclusive and diverse since 2020. Recently, during the 95th Oscars on March 12, the large number of non-English speaking films nominated outside of the international film category led junior Ananya Nadathur to question the need for a “Best International Feature Film” category.

“The Oscars has grown from a Hollywood, mainly white-only thing, to more of a global position — global films also strive to have a part in the Oscars,” Nadathur said. “I feel like it would also be better for the awards show itself if instead of just having an international film category, they just opened up every film category to global film industries.”

According to NPR, the Oscar for the “Best International Feature Film” category has gone to a European territory 58 times since the category’s introduction in 1956, with France being nominated more times than any other country. Despite noting the downsides of this category, freshman Giljoon Lee said that the international film category brings awareness to non-English speaking films within a Eurocentric award show.

“In a perfect society, in a perfect world, movies are just movies, [and] there’s no need to divide them,” Lee said. “There’s so many categories for English language films: Best Director, Best Actress, Best something, something, something. For international films, it’s just one category for so many films that were released that year. So having [the ‘Best International Feature Film’] category is perhaps the best way to force a Eurocentric award show to recognize films that are not from Western [production studios].”

However, Nadathur addresses the discriminatory nature of the “Best International Feature Film,” stating how the category tends to favor European films while underselling films produced in regions outside of Europe and America. Hence, despite American films not being included, racism still plays a key role in determining which film wins.

“Our definition of international film is really iffy because, on one hand, international film is just not American-produced, but then on the other hand, non-American actors that are still white are more likely to get nominated for different awards than like non-American actors who aren’t white,” Nadathur said. “So I mean, good for the film, good for their actors, but also there definitely is something to be said about non-American but still white films gaining privilege over non-American, non-white films.”

Lee, Nadathur and Jariwala all note how double standards continue to push through in terms of how society receives films even past the Oscars. Lee notes how although Hollywood is still the capital of film, international films are starting to share the spotlight as Hollywood shifts its focus towards blockbuster franchises, prioritizing profit over quality of content. Lee identifies this with Marvel in particular, attributing the growth in popularity of international films to Hollywood’s decline in creativity.

“I’ve seen a lack of creativity [in] a lot of bigger Hollywood films recently,” Lee said. “When you look at the earlier Marvel films, you can tell they were genuinely creative and the writing was good and the story actually made sense for once. But when you look at the films that they produce now, it’s OK, but the emotional connection is gone. You just don’t feel that anymore.”

Nadathur shares the same sentiment with Marvel films, stating how they continue to be praised despite their declining quality. However, she notes that while Western films are praised for following repetitive stereotypes, international films are often looked down upon for doing the same thing — while Marvel still has diehard fans despite its decreasing quality, international movies are often scrutinized.

“Every time a western film has a really basic plot, like a really basic romance plot, it’s considered a ‘classic’ and it gets nominated and praised for that,” Nadathur said. “But when international films — and most of my experiences, Bollywood and Tollywood films, obviously — tend to follow really cliche plot points, especially with romance or a ⁹superhero aspect [or a] violence aspect, those films are always considered cringe on social media. [There are] so many compilations of Bollywood movies being overdramatic and I feel like they’re held to [a] much higher standard.”

According to Nadathur, double standards also prevail in what genre of film is deemed trendy at a given point of time. She mainly attributes this statement with the indie genre, stating how European films tend to embody the genre and are perceived as more unique, quirky and often more intellectual. On the other hand, Asian, African and Middle Eastern films are typically excluded from the genre and this treatment, despite sharing similar plotlines, which Nadathur notes as problematic.

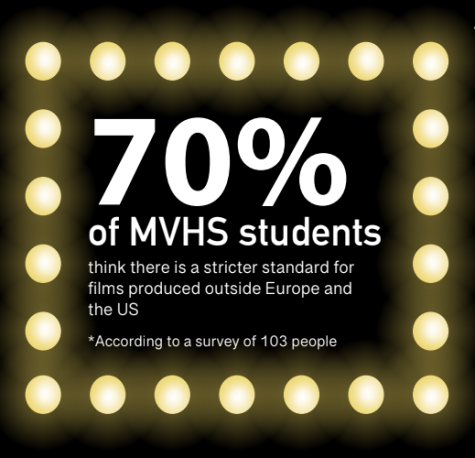

This sentiment is shared by the MVHS community. According to a survey of 103 students, 70% believe that there is a double standard for international films, particularly international films that are not of European origin.

Jariwala expands on Nadathur’s point, attributing this double standard to societal racism and reinforced stereotypes. According to Jariwala, stereotypes and predetermined expectations for international films cause viewers to have different standards, which can be harmful because it alters the lens which is used to watch and critique these films.

“Oftentimes, as people of color, there are more hoops we have to jump through,” Jariwala said. “There’s always stereotypes. We’re combating higher expectations and oftentimes, maybe that’s not the intention, but it does feel that way … But [I] will say even right now, I feel like things are getting better… there’s a lot of pressure on [The Academy]. And I do think that maybe it’s because of what happened last year, and maybe some criticism that’s happened in the previous years. But it was really nice this year. When I watch[ed the Oscars], I felt really proud after a long time.”