Art: a universal language

Exploring MVHS’s connection with art in their foreign language

March 28, 2023

During the first rehearsal of MVHS Drama’s 2019 production “The Marriage,” drama teacher Hannah Gould had the entire cast learn how to say their names and “nice to meet you” in Russian. After this, she explained the context behind the play, pertaining to the language and the society in which the play was set in. This was the first play that Gould directed at MVHS, and what was special about “The Marriage” is that the source material was entirely Russian. One of Gould’s most significant projects was translating the entire script to English while ensuring the dialogue’s cleverness and humor weren’t lost in translation.

“When I told people what I was doing for the play, people were like, ‘That’s a terrible idea,’ You’re going to try to get high school students excited about an 18th-century Russian play,” Gould said. “I was like, ‘No, no, no, trust me, it’ll be fine.’ I think that just because I was so passionate about it, and excited about it, they did end up enjoying it.”

Gould says that art exceeds boundaries and spans all languages, acting like a universal language itself. She speaks multiple languages — Spanish, French, Polish and Russian — and has immersed herself in the art of these various languages, mentioning significant works of art such as Leo Tolstoy’s “Anna Karenina” and “War and Peace.”

“[Anna Karenina is] one that I read in Russian in grad school, and it is just a really fantastic book,” Gould said. “It’s one that I want to keep going back to over and over again, and it kind of helps me understand my life and things like that. It’s one of my favorite texts of all time.”

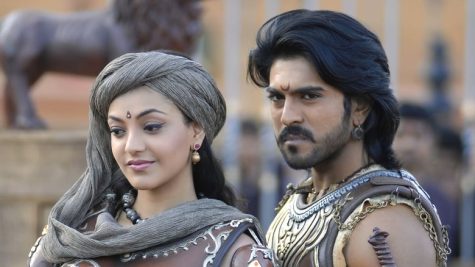

Senior Rishita Madhdhipatla, a Tamil speaker, consumes Tamilian art fairly often, usually alongside her family. Madhdhipatla has been watching various Indian movies from Bollywood (Hindi), Tollywood (Tamil) and Kollywood (Telugu) since she was 10, highlighting the film “Magadheera,” a 2009 film release that has received numerous accolades. Madhdhipatla has been speaking Tamil since she could talk, learning the language alongside English.

“It helps me connect with my family, especially back in India, because, although I don’t speak my language that well, at least the movies give us something to talk about,” Madhdhipatla said. “It’s really something that connects me and my family even when we’re not all physically together.”

Sophomore Dhruva Ramachandran, who also has an understanding of Tamil, started learning the language at the age of three, similar to Madhdhipatla. While Ramachandran enjoys listening to Tamil music more than watching movies, he still consumes both now and then. However, he does not feel as connected to the art of his culture as Madhidhipatla or Gould, finding himself wanting to return to English music and movies. Ramachandran states that he enjoys modern art more than movies, deeming the more traditional side unoriginal. Even when he chooses to watch Indian movies every now and then, usually with his family, it is a hit or miss for him — while a lot of the Indian movies he watches might be entertaining, he observes that they are also often very formulaic and cliche.

Gould, Madhdhipatla and Ramachandran all say that their parents had the biggest role in getting them involved with the art of their respective foreign languages. Gould was exposed to Eastern European culture since her parents lived there before her birth. Madhdhipatla and Ramachandran’s parents also introduced them to different art forms in their languages when they were young.

“My parents started trying to get me into [classical singing] at around the age of three or four,” Ramachandran said. “My first intro to Indian culture was through music and singing, and again, this was something my parents kind of got me into.”

Madhdhipatla, being more connected to her culture on the side of cinema, says that part of the reason she was exposed to films specifically is that her entire family had a lot of film enthusiasts.

“The movie thing is something that my family has passed down to me because a lot of my family members are like movie fanatics,” Madhdhipatla said. “And so, after watching more and more films with my family this is something that came into me over time.”

Both Ramachandran and Madhdhipatla have also taken part in producing their art of various forms in their language. Ramachandran’s parents introduced him to Indian classical singing as a child, which he has still been doing. Madhdhipatla found a love for dance at a young age, specifically Indian classical dance, or Bharatanatyam.

“[Bharatanatyam is] probably the biggest part of my life, especially now because I’m preparing for my own Arangetram, [a Bharatanatyam dancer’s debut as a solo dancer],” Madhdhipatla said. “So the past 12 years have just been a lot of dance and honestly, I hated it at first, but I think it really helped me connect with my culture.”

While Gould has not directly made art for a while, she has contributed a lot to expose audiences to the art of different cultures, and she is currently working on a project to do so.

“The only creation that I do is translation and adaptation — I like doing adaptation — my final language is always English because I don’t speak Russian well enough to create something in Russian,” Gould said. “But the project that I’m working on right now is adapting these four little tragedies by [Russian author Alexander] Pushkin into an American context and adding elements of older Russian society and aesthetics and modern American society and aesthetics and kind of mixing it all up. And so I’m creating something new and it has a lot to do with Russian but it’s in English.”

All three described in their own ways that making, consuming and spreading art are all vital parts of representing a culture and keeping it alive. Ramachandran and Madhdhipatla note that films, dances and songs have been around for ages and are a great way of preserving a culture and its history.

“I actually feel that using art as a tool is really important— it can say a lot about the culture as a whole,” Ramachandran said. “Oftentimes when I think of various cultures, I jump to the different art forms of the various cultures, and I feel like the identity of the culture is represented through its art.

Gould agrees with Ramachandran, attributing Russian culture as an example. She holds Russia to a golden standard when valuing all sorts of art like music, writing and theater. Gould explained how even in times of struggle such as a point in time in Russia where communism was extremely prevalent, there was a lot of communal support for the arts such as protecting artists, urging for exposure to more art, and funding artist endeavors. As a result of this, artists during this period were able to capture the true essence of Russian culture, emotion and thought during this era.

“I think it’s something that brings communities together, it makes communities stronger,” Gould said. “So instead of everybody just kind of being their own cyborg self, like in their little cubicle working on their computer, [art] is actually is something that can make a community strong, robust and healthy, and then it can also help preserve a record of that for people who are maybe outside of the community or in the future.”